At the time the Scopes trial came to Dayton, Tennessee a fifteen-year-old on the other side of the state, Abe Fortas, attended a segregated public high school in Memphis. He came from in a Jewish home, but—like his Eastern European immigrant father—viewed Judaism primarily as a matter of ritual. His eighth grade teacher called him “a darling boy, straight, honorable and smart.” He worked hard, and graduated second in his South Side High School class.

As a young man, Fortas’s interests centered around music and politics. He enjoyed listening to the blues on Beale Street, within walking distance of his home, and became a skilled violinist and a member of a local band, the Blue Melody Boys. His passion for debate made him a formidable member of the Southwestern College (now Rhodes University) debate team (he compiled a 17-3 record) and led him to the presidency of the Nitist Club, a philosophical debating society on the Southwestern campus in Memphis. For his own presentation to the group, Fortas chose the topic, “Is Life Worth Living?” and argued that it was not. Fortas’s politics tilted decidedly to the left during his college years. At age eighteen, he urged classmates to vote for socialist Norman Thomas as President.

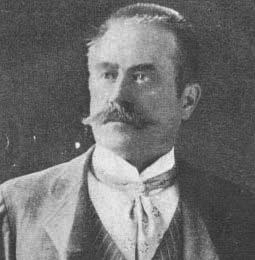

Fortas left Tennessee and headed east in 1930. He attended Yale Law School, held several different posts in federal agencies, and worked two decades in a corporate law firm he started with two associates. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson nominated Fortas for a seat on the United States Supreme Court.

In the early 1960s, a group of educators and scientists funded by the National Science Foundation produced a new biology textbook that emphasized evolution. School districts around the country quickly adopted the new book, even in the three southern states where antievolution laws remained in place. In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board moved to adopt the new biology book in 1965. The book it replaced had made no mention of evolution. Arkansas, at the time, had an antievolution law dating to 1928 that made it a crime to “to teach the theory or doctrine that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals.”

Susan Epperson, a young tenth-grade school biology teacher at Little Rock’s Central High, became the plaintiff in suit instituted by the state teacher’s organization to test the antievolution law in state court. She alleged in her complaint that she wanted to teach from the new textbook, but feared criminal prosecution and dismissal if she did so. At trial, the attorney general of Arkansas sought to show the reasonableness of the state law. He pointed to a recently exposed hoax involving the Piltdown fossils as evidence that evolution was an unproven theory at best. The attorney general’s argument, however, left the judge, Murray O. Reed, unimpressed. He concluded that the statute “tends to hinder the quest for knowledge, restrict the freedom to learn, and restrain the freedom to teach.” The law, Reed ruled, violated the federal constitution.

In the spring of 1967, the Arkansas Supreme Court, without oral argument, reversed Reed’s ruling in the Epperson case. The Court’s two-sentence opinion found the anti-evolution law to be “a valid exercise of the state’s power to specify the curriculum in its public schools.” The Court did not answer the question of whether it read the law as banning all discussion of evolution, or whether it “merely prohibits teaching that theory as true.”

The teachers’ petition for review in the Arkansas case reached the desk of Justice Fortas’s young law clerk, Peter L. Zimroth. Zimroth wrote a memo to his boss advising that the petition be denied because the “case is simply too unreal.” Zimroth wrote that the state courts had not yet resolved the question of whether the statute prohibited all discussion of evolution and, more importantly, it seemed unlikely that any prosecutor would choose to enforce the law anyway. “Unfortunately,” he concluded, “this case is not the proper vehicle for the Court to elevate the monkey to his proper position.”

Fortas, however, made clear to his clerk that he wanted the Epperson case heard. In a memo to Zimroth the justice wrote, “Peter, maybe you’re right—but I’d rather see us knock this out.” Fortas’s view prevailed, and Arkansas was asked by the Court to respond to the teachers’ petition. The state filed a brief answer that reasserted the state’s position that it had the right to determine its own school curriculum. Zimroth found the state’s answer totally inadequate. “The response is as outrageous as the law which it seeks to defend,” he wrote in a memo to Fortas. Nonetheless, he held fast to his view that the Court should decline to take the case. Fortas rejected his clerk’s advice and pushed his colleagues to accept the case.

Edward J. Larson, in Summer for the Gods, attributes Fortas’s determination to hear the Epperson case to his experience as “a working-class Jewish boy growing up in the Baptist citadel of Memphis” as the controversy surrounding Scopes “swirled about him.”

References to the legendary Scopes case filled the documents submitted in Epperson’s appeal. The plaintiffs’ brief ended with a reminder of “the famous Scopes case” and the “darkness in that jurisdiction” left in its wake. The state, for its part, opened its reply by citing the Tennessee Supreme Court’s decision in the Scopes case as support for its position that curriculum matters are for the states to decide. The ACLU’s brief in Epperson said that “The Union…looks forward to its final resolution” of the controversy began in Dayton “40 years ago.”

Two days after oral argument, the justices met in conference and voted 8 to 1 to strike down the antievolution laws. Fortas’s notes of the conference show that the justices differed considerably in how they reached their conclusions. Most justices, including Chief Justice Warren, found the law “too vague to stand” and faulted the state for not showing how evolution threatened the public welfare. Justice Stewart saw the law as violating the free speech rights of teachers. For Fortas, however, the issue was religion—the establishment of religion by the state.

Fortas requested and was granted permission to write the Court’s decision. In the opening paragraph of his opinion, Fortas tied the Arkansas statute to the Scopes case: “The statute was a product of the upsurge of ‘fundamentalist' religious fervor of the twenties. The Arkansas statute was an adaption of the famous Tennessee 'monkey law' ….The constitutionality of the Tennessee law was upheld by the Tennessee Supreme Court in the celebrated Scopes case in 1927.”

The constitutional attack might have originated against an Arkansas law, but Fortas clearly meant to turn it against Tennessee’s old antievolution law as well. His opinion discusses the purposes of the Butler Act more than the Arkansas law, and he drew from the memoirs of Clarence Darrow and John Scopes to support his analysis of the antievolution law. “There is and can be no doubt that the First Amendment does not permit the State to require that teaching and learning must be tailored to the principles or prohibitions of any religious sect or dogma,” Fortas argued. In this case, Fortas concluded, that is exactly what happened: “No suggestion has been made that Arkansas' law may be justified by considerations of state policy other than the religious views of some of its citizens. It is clear that fundamentalist sectarian conviction was and is the law's reason for existence.”

Justice Hugo Black wrote a separate opinion, disagreeing with Fortas’s resolution of the case. Black suggested that the Court should never have taken--and should now dismiss—the case: “The pallid, unenthusiastic, even apologetic defense of the Act presented by the State in this Court indicates that the State would make no attempt to enforce the law should it remain on the books for the next century.” Moreover, he complained, the record failed to show “whether this Arkansas teacher is still a teacher, fearful of punishment under the Act….It may be, as has been published in the daily press, that she has long since given up her job as a teacher and moved to a distant city, thereby escaping the dangers she had imagined might befall her under this lifeless Arkansas Act.”

Black also took issue with Fortas’s conclusion that the law was plainly as attempt to aid religion. The 82-year-old justice wrote, “It may be instead that the people's motive was merely that it would be best to remove this controversial subject from its schools; there is no reason I can imagine why a State is without power to withdraw from its curriculum any subject deemed too emotional and controversial for its public schools.” Black argued that instead of establishing religion, Arkansas merely was being neutral on the issue of creation: “Since there is no indication that the literal Biblical doctrine of the origin of man is included in the curriculum of Arkansas schools, does not the removal of the subject of evolution leave the State in a neutral position toward these supposedly competing religious and anti-religious doctrines? Unless this Court is prepared simply to write off as pure nonsense the views of those who consider evolution an anti-religious doctrine, then this issue presents problems under the Establishment Clause far more troublesome than are discussed in the Court's opinion.”

The media, unsurprisingly, played the Epperson decision as the last chapter in the Scopes trial. Almost without exception, they saw it as a happy ending. Time and Life both made references to Inherit the Wind; the New York Times called the Epperson “the nation’s second monkey trial,” but one with a “strikingly different result” than the one in 1925.

The Epperson majority opinion turned out be one of the last Fortas ever wrote. Soon afterwards, President Johnson nominated Fortas for the position of chief justice, but the nomination collapsed amidst a financial scandal. Fortas resigned from the Court in 1968 and returned to private practice.