Anthony Burns (Fugitive Slave) Trial of 1854

The extradition of Anthony Burns as a fugitive slave was the most memorable case of the kind that has occurred since the adoption of the Federal Constitution. It was memorable for the place and for the time of its occurrence; the place being the ancient and chief seat of Liberty in America, and the time being just the moment when the cause of Liberty bad received a most wicked and crushing blow from the hand of the Federal Government. It was memorable also for the difficulty with which it was accomplished, for the intense popular excitement which it caused, for the unexampled expense which it entailed, for the grave questions of law which it involved, for the punishment which it brought down upon the head of the chief actor, and for the political revolution which it drew on. [ANTHONY BURNS: A HISTORY by Charles Emery Stevens (1856)]

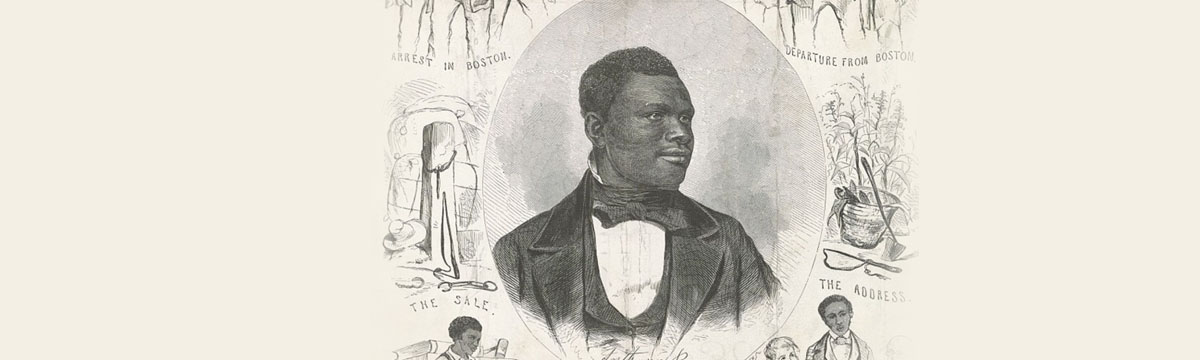

Anthony Burns worked as a slave for a series of masters in Virginia beginning at age 7. He mangled his hand in a sawmill accident when he was 12. Against odds and against state law, he learned how to read. Then, as a young man, he became a minister to the slave community.

In late February or early March of 1854, at age 20, with the help of a sympathetic sailor, Burns managed to stow away on a ship bound for Boston. He landed a couple of temporary jobs, then found work in a clothing store.

In a letter to his brother, enslaved in Richmond, Burns revealed that he was living in Boston. The letter fell into the hands of his brother’s master, who in turn conveyed it to Burn’s former master, Charles Suttle.

Suttle wanted his slave back. He went to state court in Virginia to begin the process of recovering Burns. The court declared in a transcript that Suttle had produced “satisfactory proof” of his ownership of Burns. Under the Fugitive Slave Act, such a transcript was deemed “full and conclusive evidence” of escape and that the escaped slave owed service to the party in the record. With his transcript in hand, Suttle set off for Boston to reclaim Anthony Burns.

In Boston, Suttle and William Brent, a Virginian who had purchased Burns’s service for two years, appeared before Commissioner Edward Loring. Faced with the Virginia transcript, Loring felt he had no choice but to issue an arrest warrant for Burns.

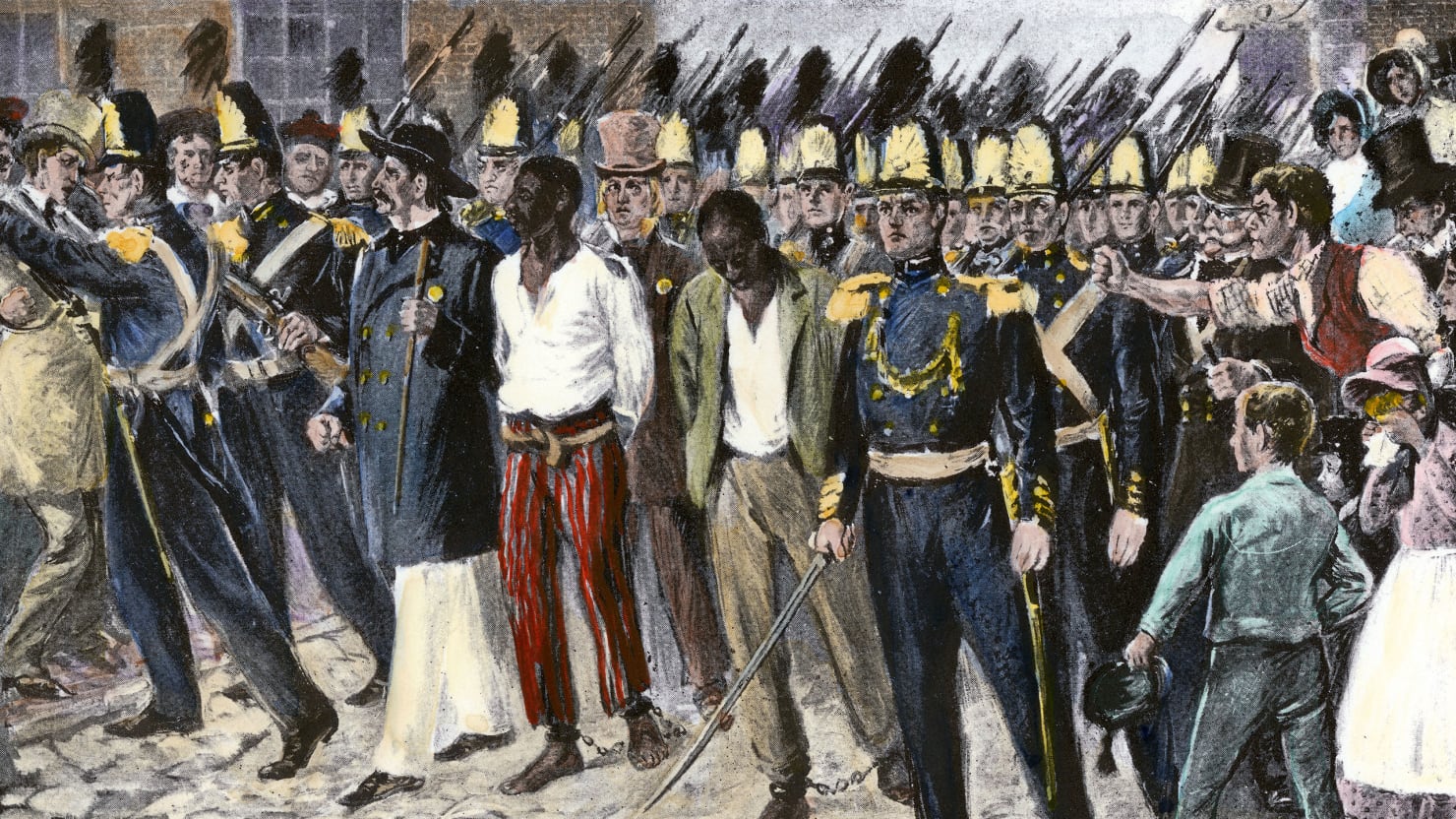

That evening, after leaving work, Burns was grabbed and carried bodily by a half dozen men to the Boston Courthouse. His captors stashed him in the jury room and locked the door. Burns was told he would face a rendition hearing the next morning.

But this was Boston, an abolitionist hotbed. And several members of an abolitionist organization known as the Vigilance Committee showed up in the courtroom the next morning. An antislavery lawyer named Henry Dana offered Burns his services. Burns was reluctant at first, but after a bit of back and forth, he gave his half-hearted support to a defense.

Dana then moved quickly to secure a postponement of the hearing.

The Vigilance Committee was split between members whho favored non-violent protest in opposition to Burns’s rendition and those who favored an assault on the courthouse to free him. The thirty or so who favored the escape plan met to work out details. Meanwhile, another group of abolitionists met to discuss a plan to pay Burns’s master whatever it took to buy Burns’s freedom.

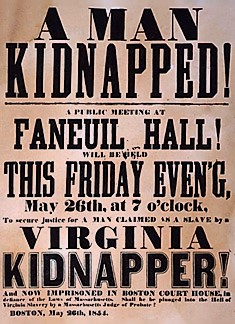

That evening a crowd of 3 to 5,000 people gathered in Faneuil Hall to protest the rendition proceedings. The abolitionist Wendell Phillips inflamed the crowd by praising the recent murder of a slave owner bent on recapturing a fugitive slave in Pennsylvania. If Burns “leaves the city of Boston, Massachusetts is a conquered state,” Phillips said....

[continued: see Anthony Burns Trial: An Account (1854)]