The Ulysses Trials

The Two Ulysses Trials: An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

James Joyce in 1922, the year Ulysses was first published in France

It is the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature….All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words. And its unclean lunacies are larded with appalling and revolting blasphemies directed against the Christian religion and against the name of Christ—blasphemies hitherto associated with the most degraded orgies of Satanism and the Black Mass.

–U. S. Attorney Martin Conboy, quoting James Douglas's comments about Ulysses in the London Sunday Express, in argument before the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in U. S. v One Book Enittled Ulyssses (5/16/1934)

Ulysses began in the mind of James Joyce in 1906 as an idea for a short story. He thought it clever to attach a Homeric-style name to a drunk he met one night in Dublin. Ulysses’ story, unlike the journey of Homer’s Odysseus, would be anything but heroic--the thoughts and ramblings of a near-middle aged, somewhat pitiable, Irish advertising salesman as he traveled around Dublin one late spring day. But the short story would become a novel, and it grew and grew over the course of 15 years of writing by Joyce in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris to a total of 732 pages in notebooks and on sheets of paper.

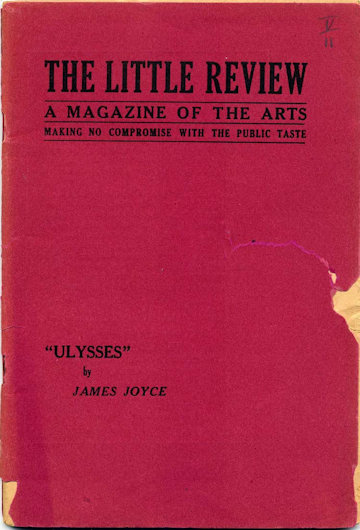

Some contemporary writers, such as T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, called Joyce’s modernist epic a masterpiece. But others just called it obscene. Before Joyce could declare a final victory, his book would be the subject of two obscenity trials in the United States. The first resulted in the criminal conviction of two daring publishers of the literary magazine The Little Review. The publishers were ordered to seize and desist publishing episodes of Ulysses, and existing copies held by the post office were burned. The second, which effectively gave Random House the greenlight to publish Ulysses in the United States, also produced a landmark opinion—an opinion which undid a repressive obscenity test which had stood for more than half a century and replaced it with one which allowed serious writers to tell stories with candor, realism, and honesty. Ulysses changed the course of literature.

The story of the Ulysses trials brings together literary geniuses, bold publishers, puritanical crusaders determined to protect the public from impure thoughts, crafty lawyers, and one of the most celebrated jurists in American history. As Molly Bloom might say: Yes!

Joyce Finds a Publisher

Margaret Anderson decided she would publish a cutting-edge literary magazine with a feminist bent. Her lively intellect, persistence, and striking beauty all served her well in pulling together funding for her venture. She secured promises of ads from publishers like Scribner’s and Houghton Mifflin, as well as donations from modernist intellectuals, including $100 from architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Margaret Anderson, publisher of The Little Review

In the inaugural 1914 quarterly issue of The Little Review, Anderson declared her magazine a place for “untrammeled liberty which is the life of Art.” She added, we are done with letting “husbands, fathers, and brothers decide for us what is best to do.” Two years after its debut, Anderson brought to the Review’s offices a kindred spirt in Jane Heap, who had fled the prairies of Kansas to join the Chicago theater scene. In Anderson’s words, “Jane and I began talking. We talked for days, months, years” and formed a “consolidation that was to make us much loved and even more loathed.”

A published complaint by Anderson concerning the quality of recent submitted manuscripts, produced a response from the poet Ezra Pound, who wrote to suggest that a place be set aside in each issue where he and T. S. Eliot might appear regularly, and where “Joyce can appear when he likes.” Pound told Anderson that if the space could be set aside, he knew of a “Mr. X” who agreed to provide funding of $750 a year for himself and the other writers he promoted. The “Mr. X” turned out to be lawyer and art and manuscript collector John Quinn—the lawyer who, for better or worse (mostly worse), would defend Anderson and Heap in the criminal obscenity trial which was to come. Pound and Quinn had first met in 1910 at Petitpas', a French restaurant and boardinghouse in the Chelsea district of Manhattan, which was a regular gathering place for poets. John Butler Yeats introduced the two men.

Yeats at Petitpas' by John Sloan (1914)(Yeats is second from right)

In May 1917, Anderson accepted Quinn’s financial support and appointed Ezra Pound foreign editor of the Review. Pound secured for publication 21 poems from W. B. Yeats and eight from T.S. Eliot. But the biggest prize secured by Pound were episodes of Joyce’s ever-growing, evermore mystifying novel, Ulysses. In December, Joyce began sending episodes to Pound, who passed them along to Anderson. Pound knew Joyce’s material well and was aware of the risk of prosecution. “I suppose we’ll be suppressed if we print the text as it stands,” he wrote Joyce, “BUT it damnwell worth it. I see no reason why nations should sit in darkness merely because Anthony Comstock was horrified by the sight of his grandparents in copulation.” (Anthony Comstock was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.)

Anderson loved Joyce’s first episodes. “This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have,” she told Heap. “We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.” She announced in the January 1918 issue of The Little Review that the magazine was “about to publish a prose masterpiece.”

Ezra Pound (far right), John Quinn (standing), and James Joyce (far left)

Between 1918 and 1920, eleven chapters (“episodes”) of Ulysses were serialized in The Little Review. John Quinn was not among the book’s fans. He referred to the first episode as “the Joyce thing” and dismissed later episodes as “toilet-room literature” that would be “subject … to damnation in thirty seconds by any court or jury.” Not exactly the support you might want from your attorney. Quinn announced he would no longer provide financial support for the Review and in an October 1918 letter to Pound, referring to Anderson and Heap, said, “They can go to hell as far as I’m concerned.”

Postal authorities began taking a hard look at Joyce’s contributions to The Little Review. Whether because of a complaint or on his own action is unclear, but the Postmaster decided to suppress the January 19 issue of the magazine containing Joyce’s seventh episode, Lestrygonians. It appears the Postmaster was most moved to act by a passage in which Joyce has Leopold Bloom, one of the book’s two main protagonists, remembers his first sexual encounter with his wife, Molly: "Wildly I lay on her, kissed her: eyes, her lips, her stretched neck beating, woman’s breasts full in her blouse of nun’s veiling, fat nipples upright. Hot I tongued her. She kissed me. I was kissed. All yielding she tossed her hair. Kissed, she kissed me."

The next issue of The Little Review was also suppressed, although it is not clear why. Anderson had taken the precaution of excising a description of the protagonist Stephen Dedalus pissing on his doorstep and a couple of lines in a ballad referring to masturbation. The lack of obviously erotic material in episode 8 led Quinn, at the request of his clients, to file a memorandum with the Solicitor of the Post Office arguing against suppression of the issue. The Solicitor replied that the suppression was based “on the magazine as a whole.”

Undeterred, The Little Review continued to publish additional chapters from Ulysses until January 1920, when the entire issue was seized and burned by the Post Office based on Joyce’s words in the Cyclops episode.

Anderson said the burning of her magazine felt “like a burning at the stake.” She wrote about her “excitement of anticipating the world’s response to the literary masterpiece of a generation” and then, instead, receiving a notice from the Post Office: “BURNED.”

The First Ulysses Trial (The Criminal Trial of Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap)

The Nausicaa episode published in the July-August issue of the Review finally prompted authorities to file a criminal complaint against Anderson and Heap for violating New York’s obscenity law. . . .Continued