The discovery of the body of a thirteen-year-old girl in the basement of an Atlanta pencil factory where she had gone to collect her pay check shocked the citizens of that crime-ravaged southern city and roused its public officials to find a suspect and secure a conviction. Unfortunately, it now seems, events and the South's anti-Semitism conspired to lead to the conviction of the wrong man, the factory's Jewish superintendent, Leo Frank. The case ultimately drew the attention of the United States Supreme Court and the Governor of Georgia, but neither the Constitution nor a Governor's commutation could spare Frank a violent death at the end of a rope strung from a Georgia oak tree.

The Murder that Shocked Georgia

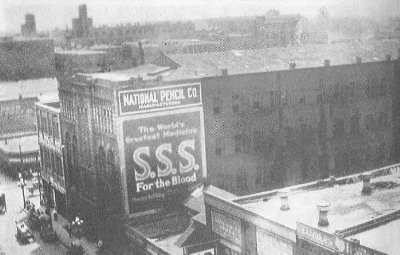

Around 3 a.m. on April 27, 1913, Newt Lee, the night watchman for the National Pencil Factory, carried a lantern with him to the factory basement to help him light his way to the "Negro toilet." When his light fell upon a prone human form, Lee called Atlanta police, who arrived ten minutes later. The body was that of a thirteen-year-old girl. Her skull was dented and caked with blood. A piece of jute rope was wrapped around her neck. A worker at the factory called to the scene identified the body: "Oh my God! That's Mary Phagan."

Mary Phagan

The murder of Mary Phagan shocked a city already reeling from crime, violence, and desperate working conditions. Within the previous decade, Atlanta had experienced a serious race riot and recorded the highest arrest rate of any major city in the country. Child labor laws were widely ignored and children worked for as little as 22 cents a week. The Mary Phagan murder unleashed a pent-up frustration with the pathological conditions of the city. Ten thousand mourners lined up to view Phagan's body and an angry citizenry demanded that the young girl's murder be avenged. Atlanta's mayor told police: "Find this murderer fast, or be fired!"

The crime scene investigation turned up two puzzling notes scrawled on scraps of yellow paper. One seemed to identify the murderer ("a long tall negro black that hoo it wase"), while the other suggested that the writer was told by the actual murderer to throw suspicion elsewhere ("he said he would love me...play like the night witch did it but that long tall black negro did buy his slef.") Oddly, detectives initially paid little attention to the notes, which would later play a critical role in the trial and its subsequent review by the governor, and focused more on other physical evidence. Detectives seemed even less interested in another piece of evidence that would influence later assessments of guilt: a human feces ("something that looked like a person's stool," as it was later described) at the bottom of the elevator shaft near where the body was found. When the elevator descended to the basement, the foul odor that was released eliminated doubts as to the nature of the substance. The sloppy investigation also left untested bloody fingerprints on a basement door and on the dead girl's jacket.

Ignoring some of the more obvious clues, authorities instead developed a theory that the murder took place near a lathe in a workroom outside Leo Frank's office and that the body was dragged to the elevator and taken to the basement. The theory was based on what appeared to be bloodstains near the lathe, as well as hair in the work area that seemed to match that of Mary Phagan's.

Leo Frank

Although suspicion at first had focused on the watchman, Newt Lee (who was arrested, grilled for three days, and locked in the city jail), testimony at a Coroner's inquest began to make police think that Frank might have been the actual perpetrator. A young friend of Mary's, George Epps, said that Mary said that Frank had made advances towards her. Several other employees at the factory also claimed they had seen Frank flirt with various females at the plant. An additional development convinced Solicitor Hugh Dorsey that the time had come to seek a murder indictment against Leo Frank. It came in the form of an affidavit from Nina Formby, the owner of a "rooming house," stating that Frank had made repeated calls to her on the day of the murder attempting to reserve a room for himself and a girl. (Formby's claims were later contradicted by the maid at the rooming house, who said no calls were made that day and, if they had been made, she would have picked up the phone.) On May 24, a grand jury granted the indictment sought by Dorsey.

Even as the jury was indicting Frank, reports surfaced that a 27-year-old black sweeper at the factory named Jim Conley admitted to having written the murder notes found near Mary's body. Conley was the same man who had been observed washing blood from a shirt by a foreman at the plant--a piece of evidence that detectives were surprisingly incurious about when they heard from the foreman two days after the crime. Conley claimed that he wrote the murder notes at the behest of Frank who, he said, had called him into his office the day before the murder. The improbability of the plant superintendent taking a black sweeper into his confidence concerning a murderous plot, and asking him to pen such strange notes, was apparent to some in the press and even to authorities who had trained their suspicion on Frank. Long sessions with Conley produced a second, and then a third, affidavit modifying the tale told in his original May 24 statement. In his revised story, Conley claimed that Frank had asked him to guard the door while he, presumably, engaged in some sexual activity with Phagan. But things went wrong and Phagan fell against a machine in the metal room and then Frank requested Conley's help in disposing of the body. Together the two men dragged the body to the elevator, took it to the basement, and dumped it in the corner. Only then, to throw police off the track, did Frank ask Conley to write the two murder notes. Authorities, seemed to view Conley's third affidavit as the nail in Frank's coffin, calling it "the final and conclusive piece of evidence...against Frank." Conley's admission caused the grand jury to move to indict the sweeper, but it dropped the matter after Dorsey convinced them that an indictment might jeopardize the state's case against Frank.

Jim Conley

Hate for Leo Frank came easily for many in Georgia. Frank was a Yankee Jew; Mary Phagan was (as one local man said) "our folks." He became, in the words of historian John Higham, "a symbol of the northern capitalist exploiting southern womanhood." The fact that the violation occurred in the very factory where the young Mary worked long hours for pitiful wages made the crime seem all the more reprehensible.

The Trial of Leo Frank

As the July 28 date for the opening of the Frank trial approached, Atlanta detectives, Solicitor Dorsey, and Conley's own lawyer, William Smith, engaged Jim Conley in what later be called "midnight séances": late-night sessions designed to turn Conley into the most effective possible prosecution witness. The men smoothed and refined the content of the sweeper’s testimony, as well as educated him on the importance of maintaining eye contact with the jury and other fine points of polished delivery. Smith played the role of Frank's lead lawyer, Luther Rosser , subjecting Conley to test-runs of what was expected to be one of the roughest cross-examinations in Georgia's criminal trial history. Smith later candidly stated his primary goal was "to render Conley impervious to cross-examination."

Scene during opening day of the Frank trial

Judge Leonard Roan called the case of the State versus Leo M. Frank under the tin ceiling of a courtroom in Atlanta's City Hall. After each side used its twenty peremptory challenges (the prosecution struck all veniremen expressing opposition to capital punishment, while the defense used two of its challenges to remove the two African-American veniremen), a jury of twelve men, mostly under forty and married, was seated. An Atlanta newspaper declared the jury "much above average."

The Prosecution

Fannie Coleman, the mother of Mary, testified as the prosecution's first witness. She told jurors that her daughter rose about 11:00 on Saturday, had a breakfast of cabbage and bread, and left home for the pencil factory "about a quarter to 12:00." The witness hid tears behind a large palm-leaf fan as she identified the blood-stained clothes worn by Mary on the day she last saw her. Fifteen-year-old George Epps followed Coleman to the stand. Epps testified that on the day of the murder he rode the streetcar with Mary to a stop near the pencil factory, where she disembarked at 12:07.

Newt Lee provided the most important testimony of the trial’s opening day. Lee testified that at 7:00 p.m. on the evening of the murder he received a call from Frank (something that had never happened before) asking if things were okay at the plant. After telling jurors about his discovery of the body, Lee recalled what Frank told him during a break in a joint late-night interview with police two days after the murder. Complaining to Lee about his denials of any involvement with murder, Frank said: “If you keep this up, we’ll both go to hell.”

Prosecutor Dorsey and defense attorney Rosser fought each other to a rough draw over the several detectives who took the stand. Dorsey elicited testimony that supported his theory of the crime. He got officers to describe where Frank might have obtained a cord such as the one found around Mary’s neck and how Frank might have bolted the second-floor area in which the murder might have taken place. He secured testimony concerning red spots, presumably blood, found on the second floor near the alleged murder site. He found a witness to report that Frank’s wife had said her husband had downed whiskey on the night following the crime. For his part, Rosser managed to raise doubts that the red spots were in fact blood, got detectives to concede that the basement door was crowbarred (suggesting the crime took place in the basement, not the second floor), and produced testimony that a cord similar to that found on Mary could be found at many places in the building.

Leo and Lucille Frank at trial

Rosser, however, blew a great chance to explode the prosecution’s theory of the murder. Rosser argued that Frank and Conley took Mary’s body down the elevator shaft to the basement, and then dumped it in a corner. The opportunity to challenge the theory came when detective Boots Rogers testified what happened when they traveled down the elevator to begin their investigation: “When we went down on the elevator, the elevator mashed [human excrement]. You could smell it all around. It looked like the ordinary healthy man’s excrement.” In his statement to police, Jim Conley admitted depositing the excrement in the shaft—before the time of the murder. Thus, if Rosser had been on his game, he might have observed that the elevator, which always touches the bottom of the shaft, could not have been used to carry Mary’s body if Conley’s time line was accurate. But the moment passed.

Dr. Henry Harris, the doctor who conducted the autopsy of Pagan, identified strangulation as the cause of death “beyond a doubt.” He also concluded from nearly intact cabbage found inside the girl’s stomach that Mary was killed only 30 to 45 minutes after finishing her late breakfast at home. Harris also testified that “an injury had been made in the vagina some little time before death.” He also claimed to have found “evidence of violence in the neighborhood of the hymen.” (However, another prosecution doctor on cross-examination said he "saw no indication of injury to the hymen.")

The most eagerly anticipated prosecution witness, the witness upon which the whole case ultimately hinged, was Jim Conley. On the morning of his testimony, a quarter-mile long line of would-be spectators stretched from the courthouse to the state capitol. Conley, usually a man of shabby clothes and filthy appearance, wore new clothes and sported a neatly combed fresh haircut, as he walked to the witness stand. Dorsey began his examination: "Do you know Leo Frank?"

A rapt courtroom listened as Conley told his tale of the last hours of Mary Phagan’s life. Conley testified that Frank told him that a girl would be coming by for “a chat” and that he should listen for the superintendent’s foot stomp, which would be his signal to lock the front door. When he heard Frank whistle, he was to unlock the door. Conley told jurors that sometime after Mary arrived and went upstairs, he heard a scream coming from the direction of the metal room. Conley claimed to have then fallen asleep, to be woken by Frank’s stomping foot. Later, after hearing a whistle, Conley said he went up to Frank’s office where he found “Mr. Frank standing up there at the top of the step and shivering and trembling and rubbing his hands.” Conley said his boss “had a little rope in his hands” and “right funny” large eyes. According to Conley, Frank said:

“I wanted to be with the little girl, and she refused me, and I struck her and I guess I struck her too hard and she fell and hit her head against something, and I don’t know how she got hurt. Of course you know I ain’t built like other men.”

Mary Phagan was dead. Conley claimed Frank said “there would be money in it for me” if he helped dispose of the body. He claimed to have rolled the girl up in cloth and, with Frank’s help, took the body to the basement by way of the elevator. The murder notes were Frank’s idea, Conley testified. “Frank dictated the notes to me,” Conley claimed. He testified that Frank looked to the ceiling and said, “Why should I hang? I have wealthy friends in Brooklyn.” Conley said that he promised to return to the plant later and burn Phagan’s body in the basement furnace, but that he ended up a saloon, got drunk and fell asleep, and so the final disposal of the body never happened.

Conley testified that Mary Phagan was not the first female he had known Frank to approach sexually:

"I had seen...a lady in his office, and she was sitting down in a chair and she had her clothes up to here, and he was down on his knees, and she had her hands on Mr. Frank. I have seen him another time there in the packing room with a young lady lying on the table..."

Over three days and for sixteen hours, the defense hammered away at Conley. They succeeded in getting Conley to admit they he had lied several times to investigators and demonstrated that his memory, except for events specifically asked about by the prosecutor, was exceptionally poor. Still, however, for all of Luther Rosser's assumed prowess as a master cross-examiner, Conley remained unshaken when it came to the key parts of his testimony.

The Defense

The defense had several goals. First, they hoped to cast serious doubt on the prosecution's time line and show that Frank had no opportunity to commit the murder at the time Conley said he did. Second, the defense planned to produce a series of character witnesses who, it hoped, would convince the jury that Leo Frank was not the type of man to assault a thirteen-year-old worker at his plant. Third, it hoped that by putting Frank himself on the stand they could present a more plausible account for Phagan's murder, laying the deed squarely on Frank's principal accuser, Jim Conley.

Collectively, the defense's time line witnesses managed to account for all but about eighteen minutes (from 12:02 to 12:20) of the period of time in which the Phagan murder had to have taken place. Witnesses directly contradicted Conley's account by placing Frank at his home around 1:30 on the day of the murder.

Over one hundred defense witnesses either attested to Frank's good behavior or Conley's bad behavior. Nearly twenty witnesses testified that Conley had a reputation for lying. The prosecution's attempt to undercut the defense effort by posing questions so outrageous that even if met with a firm denial by the witness (as they almost always were) they might damage Frank's reputation. For example, Dorsey asked one witness if he'd ever heard of Frank taking a young girl to a park, setting her on his lap, and "playing with her"? (This question prompted an outraged Lucille Frank to rise and defend her husband, shouting at the prosecutor: "No, nor you either--you dog!") Another witness was asked whether he had heard stories of Frank "playing with nipples." Dorsey also hinted through his questions on cross-examination that Frank was a homosexual, such as when the prosecutor inquired of a young office boy whether Frank had made improper sexual advances toward him.

On August 18, 1913, a pale Leo Frank, with hands clasped, began four hours of testimony that included a personal history and explanation of his supervisory duties at the pencil factory. On the day of the murder, Frank said, he checked a large number of invoices to ensure their accuracy. He was so occupied when Mary Phagan visited his office to collect her pay envelope. Frank told jurors that at the time, he didn't even know her name: "I only recognized this little girl from having seen her around the plant." Phagan took her paycheck and left his office. Frank told jurors that he never saw Mary alive again. He admitted to being "completely unstrung" by the discovery of the body. He said the sight of "that little girl on the dawn of womanhood so cruelly murdered" was "a scene that would have melted stone." Frank called Conley's testimony "a tissue of lies from first to last" and said the story of women coming to him "for immoral purposes is a base lie." He finished his testimony with the words, "I have told you the truth, the whole truth."

Closing Arguments and the Verdict

Rebuttal witnesses for the prosecution testified that Frank had a reputation for lasciviousness. Time and time again, Dorsey asked a parade of female former employees at the pencil factory to assess Frank’s reputation concerning “his attitude toward women,” and witness after witness replied, “bad.” Most damaging, sixteen-year-old Dewey Hall told jurors that she saw Frank talking to Mary Phagan “sometimes two or three times a day” and that she also saw him “put his hand on her shoulder.” Another witness reported seeing Frank and a female worker slip into a dressing room and “stay in there fifteen to thirty minutes.” None of what the many female rebuttal witnesses had to say concerned the day of Mary Phagan’s murder, but they left little doubt in jurors’ minds that Frank was hardly a picture of moral rectitude.

In his closing argument for the prosecution, Frank Hooper called Frank a “Dr. Jekyll” who, “when the shades of night come, throws aside his mask of respectability and is transformed into a Mr. Hyde.” He told jurors to secure justice for young Mary Phagan who “went blithely to get her $1.20…not knowing the horrible death that awaited her.” Hooper employed the region’s racial stereotyping to his advantage, arguing “You know these negroes” and suggesting the thought that Jim “would have written those notes by himself is absurd.”

Defense attorney Reuben Arnold argued that Frank was a victim of rampant anti-Semitism. Frank’s great misfortune in this case, Arnold said, is that he “comes from a race of people that have made money.” Arnold told jurors that “if Frank hadn’t been a Jew he never would have been prosecuted.”

Turning to the prosecution’s evidence, Arnold dismissed the testimony of Frank’s lasciviousness as the bitter words “of disgruntled former employees.” Arnold continued: “Deliver me from these prudish fellows that never look at a girl and never puts his hand on her and is always talking about his own virtue.” He reminded jurors that “we are not trying this man for everything that might have been said about him; we are trying him for murder.” The real criminal, Arnold insisted, was Jim Conley who “lay in his cell and conjured up” the “monstrous story” he has told. The story was preposterous, he said, and contradicted on numerous points by the evidence. Arnold suggested that the murder was committed by “a drunken, crazed negro, hard up for money.” He theorized that when Conley grabbed for Mary’s bag, she might have fallen and then been pushed into the nearby elevator shaft. The several witnesses who placed Frank’s whereabouts around the time of the murder made in “as clear as a holy writ that Conley was lying.”

Luther Rosser followed his defense colleague with an even more venomous, and undeniably racist, attack on the prosecution’s chief witness. Rosser told jurors: “Conley is a plain, beastly, drunken, filthy, lying nigger with a spreading nose through which probably tons of cocaine have probably been sniffed.” The prosecution tutored Conley and tried to “make him look like a respectable negro,” but the jurors shouldn’t allow themselves to be fooled by “a trained parrot.” He concluded by telling jurors that if they believed Jim Conley “it will be a shame on this great city.”

Prosecutor Hugh Dorsey

Hugh Dorsey, for the state of Georgia, had the last word. He accused the defense attorneys of appealing to racial prejudice to salvage a losing case. He denied that Frank was prosecuted because he was a Jew, observing: “This great people rise to heights sublime, but they sink to the depths of degradation, too, and they are amenable to the same laws as you or I and the black race.” Later in his argument, Dorsey faced Frank and stated the prosecution’s theory of the murder: “You assaulted her, and she resisted. She wouldn’t yield. You struck her and you ravished her and she was unconscious.” You killed Mary Phagan, Dorsey told Frank, “to save your reputation, because dead people tell no tales.” Concluding, Dorsey said “there can be but one verdict” and that, he told the jury twelve times between the rings of the bells of a nearby church as it signaled noon, is “guilty!”

The jury, balloting twice, deliberated less than two hours. Asked by Judge Roan whether the jury had reached a verdict, jury foreman Fred Wilburn replied: “We have, your honor. We have found the defendant guilty.”

People leaving the courtroom were greeted by an astonishing spectacle. For blocks around, cheering people filled the streets of Atlanta.

The next day, Judge Roan pronounced sentence. He ordered that on October 10, 1913, Leo Frank “be hanged by the neck until he shall be dead, and may God have mercy on his soul.”

New Evidence and Appeals

While Frank settled into his cell at the Fulton County Tower, his lawyers prepared a motion listing 115 reasons he was entitled to a new trial. The reasons included Judge Roan's decision to leave Jim Conley's explicit sexual testimony in the record and the alleged pre-trial bias of two of the jurors. One of the jurors, buggy salesman Atticus Henslee, was quoted as telling fellow members of the Atlanta Elks Club, two days after the indictment against Frank was returned by the grand jury, "I'm glad they indicted the goddamn Jew. They ought to take him out and lynch him, and if I get on that jury I'll hang that Jew for sure." (The prosecution later countered the defense statement concerning juror Henslee with surprising statements by fellow jurors that Henslee was the lone hold-out for Frank on the first ballot.) The defense motion also focused on the murder notes which Reuben Arnold described, in arguments on the motion before Judge Roan, as "negro notes from beginning to end." Arnold argued that it would make no sense for Frank to have ordered the notes written since, according to Conley, he had also told Conley to burn the body in the basement furnace to prevent its discovery. Arnold concluded his argument with the words, "As God is in the heavens above, I believe that in yonder cell rests an innocent man." Roan rejected the defense motion, but he added an unusual personal statement. Roan said: "Gentlemen, I have thought about this case more than any other I have ever tried. I am not certain of this man's guilt...But I do not have to be convinced. The jury was convinced."

On February 17, 1914, the Supreme Court of Georgia, in a 142-page decision, rejected Frank's appeal by a 4 to 2 vote. The two dissenters concluded that Conley's testimony about Frank's sexual encounters was designed "to prejudice the defendant in the minds of the jurors and thereby deprive him of a fair trial."

In the weeks after the bad news from the Georgia's Supreme Court, Frank took heart from developments that pointed towards his eventual vindication. First came word that the hair found near Frank's office which the prosecution claimed came from the head of Mary Phagan actually came from another girl. The doctor who performed the microscopic examination of hair specimens told reporters that he had informed the prosecution of his findings before the trial, but that Hugh Dorsey said "he would let the matter end there." Then came retractions. Nina Formby, who had in a May deposition said that Frank had called her seeking a room for a romantic liaison with a girl, admitted that no such call was ever made and claimed that two detectives had encouraged her to swear falsely. Young George Epps also said that he was urged by investigators to testify that Mary had told him that she was worried about Frank's sexual advances. Also strengthening the defense case was a statement by a pencil factory worker that Conley had attempted to sexually assault her, but that she managed to escape by jumping to the stairs "and running as fast as I could." At his March sentencing hearing, Frank confidently told the judge, "I am innocent of this crime and the future will prove it."

Newspapers, previously silent on the question of Frank's guilt, began to take sides. The Atlanta Journal ran a headline, "Frank Should Have a New Trial." The New York Times crusaded for Frank's cause, running twenty-five articles on the case over the course of a month, including one headline that read: "Frank Convicted by Public Clamor." Meanwhile, Tom Watson, publisher of a populist (and popular) magazine campaigned non-stop for Frank's execution. Watson argued that Frank, the "decadent offshoot of a great people," was suggesting that he was getting special treatment "because of his race."

While the debate over Frank's guilt or innocence intensified, Jim Conley was tried and convicted for his role as an aider and abettor in the Phagan murder. Conley received a one-year sentence.

Based on the new evidence, the defense filed what was called in Georgia, practice an extraordinary motion. The defense motion cited the recent wave of retractions, the revelation about the hair evidence, and an affidavit by Annie Maude Carter, who said that in return for her accepting his jailhouse offer of marriage, he confessed to murdering Mary Phagan. Carter said that Conley admitted to striking Mary with his fist, "knocking her down" and "dropping her through the [scuttle] hole" to the basement, and then hitting on a plan to lay the blame on the night watchman, Newt Lee. A statement by the pastor at the Plum Street Baptist Church was also included in the defense document. The pastor said that he had overheard Conley confess his crime to another man in an alley two nights after the murder. Unfortunately for the defense, the pastor later admitted that his statement was false and that he offered the statement because defense attorneys and investigators "were just handing money out." The fiasco with the pastor, and the resulting publicity concerning the techniques of defense investigators, doomed the defense's extraordinary motion. On appeal, the Georgia Supreme Court upheld the denial of a new trial. One dissenting justice found merit in the defense claim that the enforced absence of Frank from the courtroom at the announcement of his verdict (a move proposed by Judge Roan to protect the defendant's safety from the mob) violated Frank's right to due process of law.

The defense's next step was to file for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court arguing that the prejudicial courtroom atmosphere and Judge Roan's exclusion of Frank from the courtroom violated the U. S. Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment. Following the expected rejection of the writ in federal district court in Georgia, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. On April 19, 1915, the Supreme Court ruled that errors of law, such as cited by the defense in its brief, could not be reviewed by habeas corpus. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes dissented. The dissenters found "the presumption overwhelming that the jury responded to the passions of the mob." Holmes wrote that "Mob law does not become due process of law by securing the assent of a terrorized jury."

Commutation and the Case's Tragic End

After Georgia's Prison Commissioners voted 2 to 1 to refuse clemency, Frank's last hope lay with Georgia's soon-to-be-departing governor, John M. Slaton . The defense case for clemency was bolstered by the unusual admission by Jim Conley's own lawyer, William M. Smith, that his client had murdered Mary Phagan. Smith said that with his client convicted for a crime that he could not be re-tried, he now saw it as his duty to step forward and try to save an innocent life. Over 100,000 letters requesting commutation poured into the Georgia Governor's office. On the other hand, firebrand Tom Watson warned that if the decision of the jury and the courts were to be undone "there will almost inevitably be the bloodiest riot known in the history of the South." Privately, Watson let it be known to Slaton that he would throw his important support behind a Senate bid if only the governor would let Frank hang.

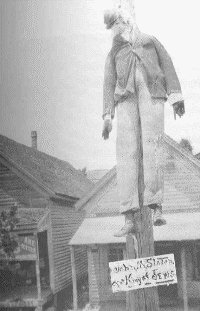

Slaton, however, took his responsibilities seriously. He carefully reviewed the record and he considered a letter from Judge Roan asking him to rectify the mistake he had made in sentencing Frank to death. He paid special attention to Smith's statement concerning Conley's alleged confession and to Conley's murder notes. Finally, after completing his review, Slaton told his wife: "I may mean my death or worse, but I have ordered the sentence commuted." Before public announcement of his decision, Governor Slaton ordered Frank transported from the Atlanta jail to Georgia's prison farm at Milledgeville, where he believed Frank could be better protected. Slaton's order commuted Frank's sentence to life in prison. Privately, Slaton told friends that he believed Frank was innocent, and that once the public came around to the same conclusion, if would be safe for the next governor to grant Frank a full pardon. When the announcement of the commutation came, protesters demonstrated and burned Slaton in effigy. A dummy hanging in Phagan's hometown of Marrietta bore a sign: "John M. Slaton, King of the Jews and Georgia's Traitor Forever." A battalion of the state militia surrounding the governor's home fended off a stone and bottle-hurling mob.

For four weeks, Frank worked on the prison farm, wrote letters, and dreamed of the freedom that he thought was now sure to come. "Right and justice," he wrote to a friend, would soon hold "complete sway." More immediate concerns soon pressed in when a fellow convict took a butcher knife to the throat of Frank as he slept on a cot. Quick work by prison doctors stopped the flow of blood from the seven-inch long slash wound and Frank, to the surprise of many, survived the attack. Frank declared his recovery "little short of miraculous" and saw it as sign that "the good Lord must have in store for me a brighter and happier day." Such was not to be.

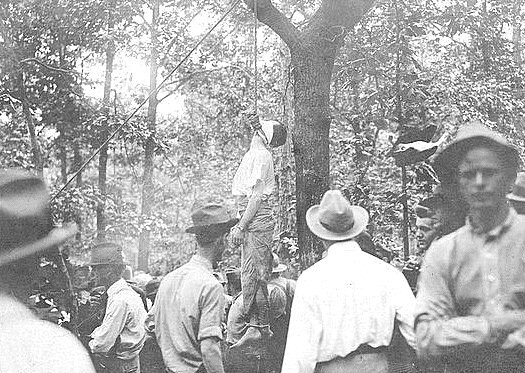

One month after the near fatal attack, on August 16, 1915, a mob of twenty-five men from Marietta stormed the prison farm at Milledgeville. The band included a clergyman, two former judges, and an ex-sheriff. Some men captured and handcuffed the prison's superintendent and warden while others overpowered the two guards on duty. The mob seized Frank and drove several hours through the night to a grove near Marietta. An effort was made to secure from Frank a confession, but the captive continued to protest his innocence to a degree that unnerved some of his captors. The lynching plot might even have been abandoned, several involved later reported, had the problem of driving Frank back to Milledgeville, in the face of a statewide manhunt, not been apparent. Several of the more determined lynchers took Frank to a large oak tree and placed a rope around his neck. Frank refused the offer of a last statement, but removed his wedding ring and asked that it be returned to his wife. The abductors hoisted Frank to the top of a table placed under the tree and then kicked the table out from underneath him. Later, hundreds of people would come to see Frank's suspended body and tear pieces of his nightshirt to save as souvenirs.

The lynching of Leo Frank

The case spurred an interest in forming organizations. A short time after the lynching of Leo Frank, thirty-three members of the group that called itself the Knights of Mary Phagan gathered on a mountaintop near Atlanta and formed the new Ku Klux Klan of Georgia. Meanwhile, members of an outraged Jewish community met to create the Anti-Defamation League to combat anti-Semitism.

The trial also helped catapult Hugh Dorsey to the Georgia governorship in 1916.