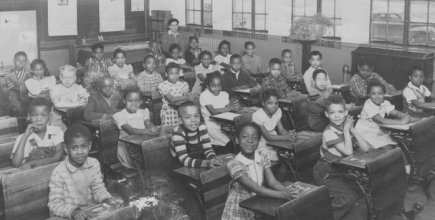

(L to R: Vicki Henderson, Donald Henderson, Linda Brown, James Emanuel, Nancy Todd, and Katherine Carper)

Photo by Carl Iwasaki/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka is widely known as the Supreme Court decision that declared segregated schools to be "inherently unequal." The story behind the case, including that of the 1951 trial in a Kansas courtroom, is much less known. It begins sixty miles to the east of Topeka in the Kansas City suburb of Merriam, Kansas, where Esther Brown, a thirty-year-old white Jewish woman, became incensed at the local school board's reluctance to make modest repairs in a dilapidated school for area black students, even while it passed a bond issue to construct a spanking new school for whites. Eventually, Esther's empathy would cause her to push the state's NAACP chapter to launch a campaign to end segregation in Kansas schools--a campaign that would lead to victory on May 17, 1954 when a unanimous Supreme Court declared that the Topeka Board of Education's policy of segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution.

Segregation in Topeka

In 1876, Kansas required that all of its public schools be open to all students, regardless of their race. Just three years later, however, the legislature backed away from its enlightened approach to racial issues, and authorized school boards in cities of over 15,000 persons to establish separate black and white schools for elementary and junior high students. Topeka exercised its option to segregate its elementary schools, and the Topeka School Board's policy of segregation was upheld by the Kansas Supreme Court in 1903, seven years after the U. S. Supreme Court upheld the principle of "separate but equal" in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. It would be more than four decades before another challenge to segregation in Topeka's elementary schools would be mounted.

At the end of World War II, Topeka was a Jim Crow city in some respects, but not in others. In the capital of Kansas, a city of about 80,000, the 7,000 or so black residents could sit where they wished in buses, enjoy integrated waiting rooms at train stations, and attend integrated junior high and high schools. On the other hand, Gage Park Swimming Pool was for whites only, and many of the city's movie theaters, restaurants, and hotels practiced racial discrimination. And although Topeka High had an integrated student body, it had separate sports teams and cheerleading teams for blacks and whites. The black basketball team was called the "Ramblers" and the white team was the "Trojans." Blacks and whites had separate student governing bodies and generally sat at separate tables in the school cafeteria.

Topeka operated twenty-two elementary schools at the time the Brown suit was filed in 1951, eighteen schools for white children and four for the city's black students. In many cases, black students were forced by the policy of segregation to attend a designated black school far from their homes when a much closer elementary school, open only to whites, was nearby.

The NAACP Takes Action

Topeka was not the only place in Kansas where segregated education existed in the elementary schools in late 1940s. In the suburban Kansas City neighborhood of South Park, white students in 1948 could look forward to moving into a brand new brick school, while the areas blacks attended the 88-year-old, two-room Walker School, a facility without indoor plumbing, a cafeteria, or even a principal. When Esther Brown learned from her black maid about the abysmal conditions at the Walker School, she began a campaign to improve the facility. She took her complaints to the all-white School Board. When the Board agreed only to make minimal improvements, such as installing new light bulbs, Brown left the meeting feeling "nauseated." Brown stepped up her efforts, organizing meetings of African American parents and trying to rally white parents to join her cause. Faced with continued Board intransigence, Brown enlisted a black Topeka attorney, Elisha Scott, to file suit against the South Park District. Brown paid a price for her activism, as she was threatened, a cross was burned in her yard, and her husband fired from his job. Nonetheless, the lawsuit she instigated led to a victory in the Kansas Supreme Court in 1949. Webb v School District No. 90 held that blacks had the right to attend the new, previously all-white, South Park School.

After achieving success in the Webb case, Esther Brown threw her support behind efforts already under way by the NAACP in Topeka to integrate the city's elementary schools. In 1948, a loosely formed group, organized by Topeka NAACP president McKinley Burnett and calling itself "The Citizen's Committee," petitioned the Topeka School Board to end its policy of maintaining separate elementary schools for blacks and whites. The petition noted "The world is in the midst of a mighty upheaval and conditions change in the twinkling of an eye." It ended with the prayer that "the Board take cognizance of our petition and instruct its agents to adopt policies which will be an inspiration to all the people regardless of race, color or creed."

The Superintendent of Schools in Topeka, Kenneth McFarland, adamantly supporting keeping the city's elementary schools segregated. Even many of the city's black teachers were content with the status quo, fearing that their jobs might be in jeopardy in a fully integrated system. As one black teacher explained her opposition to integration, "Do you think the white people would have me teach their children?" The NAACP's petition requesting integration languished for two years. In 1950, McKinley Burnett gave the Board what seemed to be a threat to institute a lawsuit. Burnett later recalled telling the Board, "You've had two years now to prepare for this"--to which a board member replied angrily, "Is that a request or is that an ultimatum?"

In the summer of 1950, the NAACP's Topeka Secretary, Lucinda Todd, wrote to Walter White, president of the NAACP, to tell them that the "unbearable" situation in Topeka called for legal action. In a separate letter to White, Burnett wrote, "Words will not express the humiliation and disrespect in this matter." In response to the letters from Topeka, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in New York initiated contact with the legal team being put together in Kansas. With the help of the national organization's lead attorney on the case, Robert Carter, a complaint, for filing in federal district court, began to take shape.

A complaint requires plaintiffs, and so the NAACP began recruiting black parents of Topeka elementary school children who might be willing to participate in the lawsuit. Eventually, the Kansas branch identified thirteen willing parents, and their twenty elementary-age children, to serve as plaintiffs. The first plaintiff listed in the complaint was a thirty-two-year old assistant minister and welder named Oliver Brown, who had an eight-year-old daughter named Linda who attended all-black Monroe Elementary School.

On February 28, 1951, the complaint was filed with the United States District Court for Kansas. Trial was set for June 25.

The Brown v Board of Education Trial

Robert Carter joined Thurgood Marshall's Legal Defense Fund office after finishing his service as a lieutenant in World War II, where he had developed a reputation among white officers as "an uppity Negro" for his insistence upon equal treatment. As a member of a team of lawyers working to end segregation in the nations' schools, Carter advocated bringing social psychologists into the cases. Carter believed, and eventually the U. S. Supreme Court would prove him right, that demonstrating how segregation adversely affected the ability of black students to learn in the classroom might be the key to winning in the courts. Before heading west to Topeka to assume command of the Brown case, Carter turned to his junior LDF colleague, Jack Greenberg, and assigned him the task of locating expert witnesses willing to testify at the Brown trial.

As the trial date approached, Carter and Greenberg and various NAACP expert witnesses began settling into hotel rooms arranged for the group by Esther Brown. Esther booked Carter and Greenberg into one of Topeka's "colored" hotels, but the lawyers found the room sufficiently scruffy that they promptly relocated to a home of a local NAACP member.

The two NAACP attorneys and the local NAACP attorneys met, a bit uneasily, to decide on strategy for the trial. Topeka attorney John Scott found Carter overbearing: "He knew what he wanted and implied that this was the way it was going to be." The trial would take place before a three-judge panel that included Walter Huxman, a tough-minded conservative Democrat and a former governor of Kansas, Arthur Mellott, and Delmas Hill. Defending the Topeka School Board was Lester Goodell, former prosecuting attorney for the county of which Topeka was the seat. Goodell certainly was not an ardent segregationist, and local attorney for the plaintiffs, John Scott, later questioned whether "Goodell's heart was really in this case."

The first witness called by Robert Carter was Arthur Saville, a former member of the Topeka school board who had just been swept out of office in an election less than three months earlier. Carter hoped to probe the reasons for the school board's policy of segregation, but Judge Huxman quickly cut off this line of questioning, declaring it irrelevant to the issue in the case, whether or not the board's policy violated the equal protection rights of the plaintiffs. Carter then turned to his next witness, former Superintendent of Schools Ken McFarland, who also was recently removed from school board politics, having just resigned in the face of a financial scandal. Carter's examination of McFarland also proved rather pointless, other than gaining the concession that the board's policy sometimes meant that black children would have to travel a greater distance from their homes to their schools than they otherwise would. McFarland pointed out that the district supplied buses for black children, but not for whites, to alleviate the effects of their sometimes extended journeys from home.

Each of the plaintiffs was given his or her chance to testify. Questioned by local attorney Charles Bledsoe, Oliver Brown appeared nervous on the stand. Judge Huxman had to urge Brown to speak up. Eventually, however, Brown's story came out. He testified that Linda had to leave home at 7:40 each morning and walk through the dangerous switching yards of the Rock Island Line on her way to the bus stop where she would be picked up and taken to the all-black Monroe Elementary School. He said the bus was often late and that "many times she had to wait through the cold, the rain and the snow until the bus got there." Moreover, Brown said, the bus schedule was inconveniently timed, forcing Linda to wait for up to ninety minutes some days until the school doors opened at nine. When Bledsoe asked Brown if he would prefer to have Linda attend the much closer Sumner School, Goodell objected. Judge Huxman said the court could take judicial notice of the fact that parents almost always would prefer to have their children attend a school closer to home than one far away. After a few meaningless questions on cross-examination, Oliver Brown was excused--and took his place as a footnote in history books.

Much of the testimony from the plaintiffs was repetitive, each explaining the travel inconvenience caused for their children by the policy of segregation. Standing out from the testimony of the other plaintiffs was that of Silas Fleming, who asked the court if he could say why he joined the suit. When Judge Huxman replied, "All right, go ahead and tell it," Fleming said "it wasn't to cast any insinuations that our teachers are not capable of teaching our children because they are supreme, extremely intelligent and are capable of teaching my kids or white kids or black kids." Rather, Fleming testified, he became a plaintiff because he was "craving light--the entire colored race in craving light, and the only way to reach the light is to start our children together in their infancy and they come up together."

No witness in the Brown trial spent more time on the stand than Hugh Speer, chairman of the education department at the University of Kansas City. For over two hours, Speer testified about ways in which Topeka's all-white elementary schools were superior to those set aside for blacks. Although the plaintiffs hoped to convince the courts that separate education is inherently unequal, they thought it advisable to present evidence supporting their fallback position: segregated schools in Topeka are not, in fact, equal. Speer testified that the all-black schools were, on average, six years older than the all-white schools, but generally had to concede that physical and curricular differences between white and black schools were small. In fact, in some respects the black schools provided arguably better educational opportunities; Speer testified that the average class size in white kindergartens was 42, but only 25 in black kindergartens. Speer seemed most determined, however, to argue that the effects of differences in the schools on the quality of education were smaller than the adverse effects from segregation itself. Speer told the court, "If the colored children are denied the experience in school of associating with white children, who represent 90 percent of our national society in which these colored children must live, then the colored child's curriculum is being greatly curtailed."

The most important testimony in the trial came from experts who testified about the negative effects segregation has on learning. Horace English, a psychology professor from Ohio State, told the court that the lower learning expectations that society has for blacks adversely affects their classroom performance. English testified "there is a tendency for us to live up to--or perhaps I should say down to--social expectations and to learn what people say we can learn." On cross-examination, Goodell elicited the concession from English that he had never tested the performance of African-American children in segregated schools and compared that performance to those of black children in integrated schools.

The testimony of Kansas University psychology professor Louisa Holt, further developing the theme of segregation's adverse effects on learning, provided the basis for what would be a central finding in the court's decision. Holt testified that the policy of segregation "is inevitably interpreted both by white people and Negroes as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group." She said that the internalized "sense of inferiority" of black students affects their motivation, as they fatalistically assume that any efforts to prove they were not inferior to whites "would be doomed to failure." Holt's articulate testimony captured both the court's attention and that of spectators. Richard Klugar, in his book Simple Justice, reports that after Holt left the stand one of the black mother's in attendance brought her children over to the psychologist and asked if they could shake her hands. "I want you children to remember this day for the rest of your lives," she told Holt.

The following day, lawyers for the Topeka School Board presented their witnesses. District employees testified about their efforts to maintain bus schedules, to staff and supply black and white schools on an equal basis, and to offer identical curriculums for students in both sets of schools. Superintendent McFarland defended the district's policy of segregation, arguing it was not the School Board's place to "dictate the social customs of the people." He said the Board had "no objective evidence" that the citizens of Topeka desired "a change in the fundamental structure."

The Court's Decision and the Appeal

On August 3, the three-judge panel handed down its unanimous decision. Writing for the panel, Judge Huxman (a Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals judge and a former governor of Kansas) concluded that the Supreme Court had not yet overruled Plessy v Ferguson, and the case "still presently [is] authority for the maintenance of a segregated school system." He wrote, "The prayer for relief will be denied and judgment will be entered for defendants for costs." While denying the plaintiffs relief, Judge Huxman's findings made clear that his sympathy lay with them. In a finding that would attract the attention of the United States Supreme Court, Huxman concluded:

Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of law; for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to retard the educational and mental development of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial integrated school system.

Even as the Brown trial took place in Topeka, several other challenges to segregated schools were wending their way through the courts. In Briggs v Elliot, another three-judge federal panel upheld Clarendon County South Carolina's policy of segregation. The Delaware Supreme Court, in Gebhart v Belton, found that a school board's failure to maintain truly equal facilities in black and white schools violated the Equal Protection Clause. A challenge to Prince Edward County Virginia's policy of maintaining segregated schools was rejected in Davis v County School Board. Finally, in Bolling v Sharpe, a trial court rejected the NAACP's argument that the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment required the federal government to integrate the public schools of Washington, D.C. The Supreme Court of the United States, in the summer and fall of 1952, either granted cert or noted probable jurisdiction in all five cases, and scheduled arguments for them to be heard together on December 9, 1952.

The Brown decision was especially critical to the NAACP's challenge, because Judge Huxman's finding about the psychological impact of segregation had to be accepted unless it was found to be clearly erroneous, as would his finding that the facilities, quality of staff, and quality of black and white instruction were equal. The Brown decision, more than any of the other cases, boxed the Supreme Court in. It left the Court little option but to either uphold the separate but equal education in Topeka, relying on the Plessy precedent, or to overrule Plessy and hold that segregated education was inherently unequal.

In the packed Supreme Court hearing room, Brown was the first case to be argued on December 9. Four hundred more people, about half of whom were African-American, lined the corridors in the hopes of witnessing the historic argument. Robert Carter told the justices that the court's findings in Brown meant that this case presented a challenge to the constitutionality of segregation itself, while Kansas Attorney General Paul Wilson defended the Topeka policy. Thurgood Marshall took the podium after arguments were complete in Brown, presenting the NAACP's reasons for believing that Clarendon County's policy of segregation violated equal protection principles. John W. Davis, a man who argued more cases before the Supreme Court than any other man in the twentieth-century, defended South Carolina's law. Over the next two days, justices heard arguments in the three remaining school segregation cases.

Two days after arguments, the Supreme Court met in its conference room to discuss the segregation cases. As the justices took turns expressing their thoughts, it quickly became apparent that the Court was badly split. Chief Justice Vinson argued that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment had no intention of ending all forms of segregation. Justices Black and Douglas disagreed, arguing that the Amendment was meant to protect the Negro against all forms of discrimination, which these policies clearly were. Justice Frankfurter agreed with Vinson that the Fourteenth Amendment did not abolish segregation, but suggested scheduling the cases for reargument on the question of whether equality still meant what it meant in 1868. Justice Jackson waffled, but indicated he might support finding segregation unconstitutional if the states were given reasonable time to desegregate. Justice Burton suggested that "education is more than buildings and faculties--it is habit of mind" and that segregation violates equal protection. Justice Minton argued racial classifications were unreasonable and that "segregation is per se unconstitutional." Justices Clark and Reed both indicated that they generally supported the right of states to segregate students. Adding up the votes, there were only four clear votes (Black, Douglas, Burton, Minton) to end policies of segregation. The justices voted to have the cases reargued the following term.

Before the cases could be reargued, Chief Justice Vinson died of a heart attack and was replaced by Earl Warren. There were now five clear votes for ending segregation in the schools. As Philip Elman, author of the federal government's brief in Brown would later observe, "Thurgood Marshall could have stood up there and recited 'Mary Had a Little Lamb' and the result would have been exactly the same."

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. (Chief Justice Warren, former governor of California, used his impressive political skills to discourage justices who might have been inclined to write a dissent, including Justice Stanley Reed, from doing so.) The Court held that "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place." Warren wrote:

To separate [the Negro children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs: Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children....

Integration came earlier and easier to some school districts than to others. In Topeka, which had previously integrated its junior high and high school, and where integration meant adding two to four black children to previously all-white classes, things went relatively smoothly. Within three years of the Supreme Court's decision, integration of Topeka's schools was complete. By the time the Court announced its decision in Brown, Linda Brown and the other twelve child plaintiffs had already moved on to integrated junior high schools. Linda's her two younger siblings, however, were able to enjoy the benefits of integrated elementary school classrooms.

Other school districts took the Supreme Court's language in Brown II (its 1955 decision implementing the Brown I ruling), suggesting that integration should proceed "with all deliberate speed," to be an invitation to deliberate and deliberate, and to forget about speed. A decade after Brown, most black children in the Deep South still attended segregated schools. Not until the 1960s, after much sorrow and even some bloodshed, did the use of invidious racial classifications in the public schools finally come to an end.