by Douglas O. Linder

1

Homer Adolf Plessy purchased a ticket from New Orleans to Covington and took a seat in the “white” section of the East Louisiana Railroad Company train. Railroad officials ordered Plessy to the “colored” car. When he refused, a police officer forcibly ejected Plessy and hurried him off to the parish jail in New Orleans. Officials charged Plessy with violating a recently enacted state law—one of many Jim Crow laws enacted in the late 1800s as whites moved to entrench their power in state governments--that barred persons from occupying rail cars other than those to which their race had been assigned.

Had railroad officials not been notified in advance that Homer Plessy was one-eighth black, he undoubtedly could have taken his seat in the “white” section of the train. Plessy appeared to be white. Louisiana, however, applied “the one drop rule”: anyone with one drop of non-white blood was classified as “colored” under the Louisiana code. Plessy gave up the privilege that he might have enjoyed as the result of his light pigmentation because he shared the goals of the Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law, a New Orleans group of blacks and Creoles. The Committee believed that a white-appearing plaintiff such as Plessy might be more likely to obtain the sympathy of a court reviewing the Louisiana law.

If found guilty, Plessy faced a possible fine of $25 and a sentence of up to twenty days in jail. Plessy challenged the Louisiana Separate Car Law, arguing that it violated the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of equal protection of the laws. In October of 1895, the United States Supreme Court heard Plessy’s arguments.

The Court upheld Louisiana’s Separate Car Law in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. In so doing, it announced the legal principle, “separate but equal,” that would guide American race relations for over half a century. Justice Henry Brown’s opinion, reflecting no understanding of racial realities in America, reads as though written by a Martian: “The underlying fallacy of plaintiff’s argument consists of the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction on it.” John Marshall Harlan offered a lone dissent. Justice Harlan, in a ringing passage—one suggested in a brief filed by Plessy’s lawyer, Albion Tourgee--argued “our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.”

Segregation seemed destiny in 1895. In addition to the Supreme Court arguments in Plessy, the year saw the passing of the great Negro leader Frederick Douglass and the emergence of a new black spokesperson, Booker T. Washington. Unlike Douglass, who pressed for full and immediate integration, Booker Washington accepted social separation of the races. In a famous speech delivered in September 1895 at the Cotton State’s Exposition in Atlanta, Booker Washington declared that “in all things purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” It was a message much of white America could endorse. The Atlanta Constitution wrote “the whole speech is a platform on which the whites and blacks can stand with full justice to each race.”

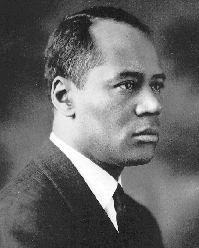

Another event in the fall of 1895 that would prove momentous for black America passed virtually unnoticed. On September 3, in a modest house just blocks from the Supreme Court, a black hairdresser named Mary Hamilton Houston gave birth to a son, Charles Hamilton Houston (after Charles I), who one day would command the attack that would kill Jim Crow.

2

Charles Houston undoubtedly owed much of his early success to his remarkable parents. His mother, a hairdresser whose clientele included senators and cabinet officers, and his father, William, a general practice lawyer, lavished love and attention on Charles. They resolved to give their intellectually curious and “serious minded” child every advantage they could. As often as their tight budget allowed, they took Charles to the zoo, concerts, and matinee theaters. They provided him with books and soon he became something of a bookworm. They provided him with a piano and soon he began to spend long hours alone practicing on the piano.

At age twelve, the Houstons gave their son perhaps his greatest gift: they enrolled Charles in the remarkable M Street High School, the first black high school in the United States. M Street proudly offered its students a traditional classical curriculum, taught by some of the best Negro teachers in America, at a time when most secondary black schools provided mostly vocational or “general” curricula. After enduring a period of adolescent restlessness during which teachers commented on his “persistently annoying conduct” and “nonchalant” attitude, Charles settled down. In his senior year, Charles earned no grade lower than “G” (“good”). His record at M Street persuaded Amherst to offer Charles a partial scholarship. The Houstons readily accepted the offer—despite the strain an Amherst education would put on their finances--and on September 13, 1911, Charles boarded a train for Massachusetts.

Charles devoted himself to his studies at Amherst. As the only black student in the class of 1915, he had “very few friends in town and rarely paid a social visit.” He described himself as “too shy or too proud” to visit his classmates in the all-white fraternity houses. The alienation he felt on account of racism seemed to spur his academic achievement and growing self-reliance. In a letter to his father he wrote, “Let us…resolve to depend upon ourselves exclusively as much as possible, in all walks of life.” He attributed his excellent grades—almost entirely A’s and B’s in an era long before grade inflation—to hard work rather than innate ability. “Genius,” he told his father, “is not half so much inspiration as it is the culmination of endless, painful and infinitely applied careful application.” In June 1915, Charles climbed the tower of Johnson Chapel, in accordance with senior tradition, to carve “CHH ‘15” alongside the initials of other Amherst graduates.

Charles Houston returned to Washington upon leaving Amherst. He began teaching English and “Negro Literature” at Howard University. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Charles was still of draft age. Anxious to avoid being “herded into the Army,” where he—like most African-Americans—might expect front-line duty and endless menial chores, he decided to become an officer. He also sensed that enlisted military service might give him the status to have “something to say about how this country should be run.” The persistent efforts of his father earned Charles a position at the first black officers’ training camp, Fort Des Moines in Iowa.

As he trained for service abroad that he received a birthday greeting from his mother on the occasion of his twenty-second birthday:

At the close of the day I turn to you my dear for a break with the tasks, for sunshine, for happiness. I have a mental picture of 22 years before me now, the canvas thank God is not full, there is room for many more years. But that part of the picture which [is finished] is satisfactory—yes, even more than I ever dreamed. God keep you my Boy, fill your life from good deeds so that when evening of life comes, that your path may be made as bright as the noonday sun by the blending of the lights from the canvas.

About the same time, he received practical advice from his father. “Charles, do your all,” he wrote. Later, in the same letter, he suggested: “If troubled with mosquitoes, use citronella.”

Mosquitoes, however, proved far less irritating to Charles than the racist attitudes of his Camp Commander Colonel Charles Ballou, who claimed his black troops lacked the “mental potential and higher qualities of character essential to command and leadership”—even though over forty per cent of his men were college graduates. In months of training at Fort Des Moines, then Camp Meade, and then Camp Dix, Charles Houston found himself harassed, abused, and reprimanded for his audacity to “raise hell” about racial discrimination and arbitrary assignments.

In his first military appointment, as judge-advocate, Charles was assigned the task of prosecuting a case involving two black soldiers charged with disorderly conduct. Charles investigated the incident and found the charges to have little substance. When he subsequently failed to win a conviction of the two accused soldiers, his superior told him he was “no good.” Charles became further embittered when he witnessed the conviction of a black sergeant—regarded by other blacks as one of the best in the company—on charges of disorderly conduct and insubordination even though the sergeant was carrying out the orders of a superior officer. Houston wrote: “I made up my mind that I would never get caught again without knowing my rights; that if luck was with me, and I got through this war, I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

Several months in the Jim Crow army camps of France strengthened Charles Houston’s resolve to fight racial injustice. Houston found that “the hate and scorn showered on Negro officers by our fellow Americans…convinced me there was no sense in dying for a world ruled by them.” Houston and other Negro officers ate on benches in the enlisted men’s area, not in the officers’ mess. They were forced to use special latrines and “showers boarded off so we would not physically come in contact with white enlisted men.” They were denied the use of white orderlies. White instructors constantly found new ways to embarrass them and portray them as ignorant. Officers warned white women such as waitresses and maids not to befriend black officers or risk inviting a sexual assault. Houston found the discrimination by American officers “obnoxious” and a violation of “every principle of Army regulations.”

In one nightmarish episode abroad, Charles found himself in the company of another black lieutenant returning to base after a late night showing of a French film. They encountered two white officers berating a black officer who had won the company of a French woman one of the white officers had decided was his. Houston recalled later, “I was not taking part in the argument but merely standing by listening. The next thing I heard and saw, a lot of white officers running down the street.” Then, according to Houston, one of the officers ran “two blocks away to where two quartermaster trucks loaded with white enlisted men were waiting to start to camp and told them to come down and lynch us…The officer who led the mob began to yelp about ‘niggers forgetting themselves just because they had a uniform on, and that it was time to put a few in their place, otherwise the United States would not be a safe place to live after they got back.’” Only the timely arrival of the captain of the American military police prevented physical violence by the white mob.

In February 1919, Charles returned to the United States. Aboard a train for Fort Dix from his arrival point in Philadelphia, Charles and a fellow black officer took a seat at table in the dining car next to a middle-aged white man. The man immediately demanded that the waiter find the Negro officers another table. Houston remembered, “I told the man we had just landed from overseas and asked him if he was going to order us to leave the table just because we were colored. He replied that he could not help it if he was from the South. He moved. We ate our meal. And I felt damned glad I had not lost my life fighting for this country.” In April 1919, Charles Houston left the army. “My battleground,” he declared, is “in America, not France.”

3

The first challenge to segregated education arose not in the South, but in pre-Civil War New England. Benjamin F. Roberts, a Negro active in the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, tried on four separate occasions to enroll his five-year-old daughter Sarah in an all-white primary school in Boston. The school committee, in turning down Sarah’s application, cited their adopted policy: “The distinction is one which the Almighty has seen fit to establish, and it is founded in the deep physical, mental, and moral nature of the two races. No legislation, no moral customs, can efface this distinction.”

Benjamin Roberts brought suit in his daughter’s name based on a Massachusetts law which provided that any child “illegally excluded from the public school” might “recover damages against the city.” Roberts retained as his lawyer Charles Sumner, later famous as a Radical Republican senator during the Civil War and Reconstruction. In 1849, Sumner presented a novel and eloquent argument before Massachusetts’s highest court. Adopting the reasoning first proposed by noted Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, Sumner contended that any classification based on race destroyed the equality of treatment to all citizens guaranteed by the Massachusetts Constitution. He attempted to demonstrate the inherent inequality of segregated schools more than a century before the United States Supreme Court would reach the same conclusion. Sumner told the justices that “the separation of the schools, so far from being for the benefit of both races, is an injury to both. It tends to create a feeling of degradation in the blacks, and of prejudice and uncharitableness in the white.” It was an argument too far ahead of its time, even in relatively progressive Massachusetts. Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw, writing for the Massachusetts Court, concluded that equality did not imply identity, and that racial classifications need only be reasonable to pass constitutional muster. No one objected to separate schools for boys and girls, Chief Justice Shaw pointed out—or separate schools for younger and older students. Why should separate schools for the two races be viewed any differently?

Charles Sumner spent the rest of his life continuing to the fight the evils of racial discrimination. In 1848, he helped form the Free-Soil Party with a platform centered on opposition to the extension of slavery into newly acquired territories. Elected to the Senate on the Free-Soil ticket in 1851, Sumner switched his allegiance to the Republican Party four years later. In 1856 he delivered a powerful speech, “Crimes Against Kansas,” that outraged many supporters of slavery, including a congressman from South Carolina, Preston Brooks. Brooks attacked Sumner on the floor of the Senate with a cane, beating the Massachusetts Senator so badly that it would be more than three years before he could resume his Senate duties. Later, as a leading spokesman for the Radical Republicans during the Civil War, Sumner pressed Abraham Lincoln to sponsor legislation freeing the slaves. During the Reconstruction Era, he helped propose the Fourteenth Amendment which enshrined in the United States Constitution the guarantee of “equal protection of the laws”—the guarantee that would eventually be the basis for the successful attack on Jim Crow.

Sumner’s efforts in the Roberts case provided an important practical lesson for future generations of civil rights lawyers. To successfully challenge segregated schools in the future would require more than political guarantees of “equality,” it would require the ability to communicate a real understanding of the effects of discrimination in education. The lesson would not be lost on the man who would lead the journey to Brown v. Board of Education.

4

As Charles Hamilton Houston returned to civilian life in 1919, he watched an America in turmoil. Race riots—about twenty-five in all—broke out during what was called “Red summer.” Boll weevil damage to the cotton crop caused thousands of out-of-work southern blacks to head to the urban North in search of jobs and a better life. Black migrants crowded into rundown tenements abandoned by recent immigrants who resented the newcomers’ competition for jobs and wages. Resentment turned to violence. Houston later described the summer of 1919 as “the greatest period of interracial strife the nation had ever witnessed.” Mobs burned homes, and shot, flogged, tortured, and lynched blacks. Race riots broke out from Longview, Texas, to Chicago to Washington, D.C.

One incident during the troubled summer of 1919 affected Houston is an especially personal way. On July 19, in the vicinity of the Gem Theater, a twenty-five-year-old black named Theodore Micajah Walker went looking for the children of a friend who worried about them being out in riot-torn Washington. Walker had just given up his unsuccessful search for the children and was returning to the home of their parents when a mob started chasing him. The crowd began yelling, “Kill the nigger, kill the nigger.” Someone hit Walker with an iron pipe. At that point, Walker drew and fired a revolver he had carried since being attacked earlier that summer. He fired low into the throng, hoping not to kill anyone, but the bullet hit and killed a nineteen-year-old white marine private. The mob dispersed. Authorities later arrested Walker and charged him with the murder. Houston’s father, William Houston, by this time a lawyer, handled exclusively civil matters--but the clear injustice of the prosecution caused the elder Houston to take Walker’s case. Despite his best efforts and those of two other attorneys, an all-white jury convicted Walker.

Through the unjust conviction of Theodore Walker, Charles came to see even more clearly how racism permeated society and violated human beings. He knew what he must do. Law school would provide him the tools to do it. In the fall of 1919, Charles Houston applied for admission to the Harvard Law School.

With his sense of purpose and hard work, Houston proved an exceptional law student. His record of mostly A’s and a scattering of B’s earned him a position on the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review—the first African-American to be so honored. Writing to his parents, Houston assessed his standing at the famous law school: “I still go my way alone. They know I am just as independent and a little more so, than they. My stock is pretty high around these parts. God help me against a false move.” Houston graduated in the top 5 percent of his class, then applied for additional work leading to a degree of Doctor of Juridical Science.

His graduate law studies took him to Spain, Algeria, and Tunisia. Standing for the first time on the African continent prompted Houston to write to his grandmother: “Thank God one of the Houston clan stands back on native soil. I count it a happy privilege.” Houston returned to a changed America in 1924 to begin his calculated assault on Jim Crow.

5

For Charles Houston, the training of black lawyers was a key to mounting a successful attack on segregation. While at Harvard, Houston wrote that “there must be Negro lawyers in every community” and that “the great majority” of these lawyers “must come from Negro schools.” It was, he concluded, “in the best interests of the United States… to provide the best teachers possible” at law schools where Negroes might be trained. Houston decided to seek a teaching position at Howard Law School, which since its establishment in 1869 had trained three-fourths of the black lawyers in the United States. He enlisted notable members of the Harvard faculty, including Dean Roscoe Pound and future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter to write letters in support of his application. Pound’s letter assured Howard that Houston “gives promise of becoming a real legal scholar.” In the fall of 1924, Professor Charles Houston began teaching “Agency,” “Surety and Mortgages,” “Jurisprudence,” and “Administrative Law” to first- and second-year law students at Howard.

Houston demanded a lot from his students. He had no tolerance for laziness and rejected out of hand complaints about assignments being too long. Houston told first-year students—as he had been told at Harvard--to “look to your left and look to your right—next year one of you won’t be here.” Houston strove to make Howard into the sort of intellectually rigorous center of learning he saw at Harvard. Later, when he became Vice Dean of the School, he lengthened the school year, toughened the curriculum and standards, and eliminated the night program. His favorite expression, repeated to faculty and students alike, was “no tea for the feeble, no crepe for the dead.” Often his demands of rigor met opposition and criticism from students and colleagues. One defender of the status quo called him “more of a machine than a man.” Another called him “insensitive.” A more charitable observer noted that although Houston “insisted upon perfection,” there “wasn’t a nicer person.” Everyone who knew Houston well conceded that he demanded even more from himself—hard work, integrity, principled conduct, thoroughness, and intellectual rigor—than he demanded from others.

Houston could be equally difficult with those close to him. His letters to his girlfriend since his Amherst days, Gladys Moran, show him to be a no-nonsense perfectionist—and more than a bit suspicious. Houston’s letters frequently took the form of lawyer-like interrogatories—a series of two dozen or more questions with space provided underneath each for Gladys to answer. Typical questions concerned her activities: “How many times have you been to the theatres, what theatres, and with whom?” or “When and how often have you been late to class?” When a letter from Gladys contained a misspelling, Houston sternly demanded that she practice the correct spelling: “You spell 'perhaps' wrongly; you spell it 'prehaps.' Write it below correctly 25 times and never spell it wrongly again.” (Gladys dutifully completed her assignment.) On one occasion, Houston learned from a friend that Gladys had received a “D” in a class when she claimed to have received a “B.” Houston’s wrote a terse letter, with every word underlined: “Dear Gladys, Why did you lie to me? Charlie.” Keeping a tidy house may not have been the first priority of Gladys, but a letter from Houston suggests that it might have been his: “And you better darned right pick up.” (Houston’s inquisitiveness and prickliness did not deter Gladys accepting his offer of marriage. The two wed in August 1924. They amicably divorced in 1937.)

Also suggestive of Houston’s values is his characteristically bold assertion, made to his students, that “a lawyer’s either a social engineer or he’s a parasite on society.” A good social engineer, as Houston saw it, was a lawyer who used his knowledge of the law to better the lot of the nation’s worst-off citizens. Houston became the very model of a good social engineer as by 1927 his professional focus shifted almost exclusively to issues of racial equality. As the director of a survey of Negro lawyers, Houston toured seventeen cities from Savannah to New Orleans, meeting with and interviewing practicing black attorneys. His study found only 487 black lawyers below the Mason-Dixon Line. In some states, the ratio of blacks to black lawyers was over 200,000 to 1. Houston drew from his study the conclusion that Howard should send as many of its graduates as possible to the South, where the need and antagonisms were the greatest. “Experience has proved,” he maintained, “that the average white lawyer, especially in the South, cannot be relied upon to wage an uncompromising fight for equal rights for Negroes.”

Two years later, as the new Vice-Dean of Howard, Houston used his base of power to declare that the “only justification for Howard Law School…is necessary work for the social good.” Houston began a program of bringing to the school for lecture programs nationally recognized civil rights figures such as Arthur Garfield Hays and Clarence Darrow. A 1931 week-long series of lectures by Darrow, the fabled defense attorney, emphasized racial inequities in the criminal justice system. Darrow told Houston’s students that nine-tenths of what one was up against in the courtroom had nothing to do with the formal law.

Houston’s efforts to elevate the status of Howard encouraged many promising black students to enroll. One of the most promising new students was a gangling young man from Baltimore named Thurgood Marshall. Marshall affectionately called his mentor “Iron Shoes” for his relentless drive. Marshall recalled, “He was a sweet man once you saw what he was up to. He was absolutely fair and the door to his office was always open.” Houston hammered into Marshall and all other Howard students the need to understand the workings of government and how they affected racial issues.

6

In its early years, the leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was predominantly white. W. E. B. Du Bois, editor of the NAACP’s official publication, Crisis, held down the only prominent black role. The years between 1916 and 1920, however, saw a concerted effort to recruit new black members in every region of the country. As a result, membership rolls increased tenfold during that four-year period. The organization’s efforts to promote anti-lynching legislation and challenge state-supported disenfranchisement and residential segregation achieved enough success to establish the NAACP as a significant player in the civil rights field.

By the time of the Depression, NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White began calling on Charles Houston to serve on the organization’s National Legal Committee. The assistance of Houston in two prominent criminal cases encouraged White to push in 1933 for Houston to take the NAACP’s most recent cause, the defense of George Crawford. Crawford stood accused by Virginia of having robbed and murdered two socially prominent white women. Blacks assumed the charge to be groundless. Houston replied to White’s request: “This case is far too big to be sloppily prepared. I would not be equal to the task because it would mean that I would have to give up all work here at the University. It would be impossible to do both jobs at the same time.” At the same time, Houston’s reply letter made plain the significance that he and most other blacks attached to the case: “if Crawford could be defended by all Negro counsel it would be a turning point in the legal history of the Negro in this country.” Eventually, the temptation to take the assignment proved too great, and Houston assumed control of the Crawford case.

Houston planned to base his defense of Crawford on the testimony of two alibi witnesses who would place the defendant in Boston at the time of the murders in Middleburg, Virginia. The plan collapsed, however, when Crawford’s girlfriend turned state’s witness and placed him near the scene of the crime. Confronting his client in jail with the new evidence, Crawford admitted to having lied about his alibi and confessed to the robbery, though he continued to insist that he was not guilty of the double murder. Evidence that Crawford pawned the gold watch of one of the victims and a note in his handwriting found in the victim's car left Houston arguing for reasonable doubt in what he first assumed to be a case of clear innocence. Threats against “the nigger lawyers” swirled around the courthouse in Leesburg as the trial opened. It took considerable courage simply to show up.

Houston and his co-counsel commuted to the trial from Washington because no one in the Leesburg area wanted to run the risk of housing them. After three days of trial testimony the jury returned a verdict of guilty, but spared Crawford’s life. Under the difficult circumstances of the trial, NAACP Director White pronounced the case an “outstanding example of a successful legal defense.” Houston described Crawford as “extremely lucky” to escape the chair. However, some people within the organization criticized Houston, calling his decision not to appeal—and thereby risk a death sentence at a new trial—a “retreat” and an “abject surrender.” They argued that the exclusion of blacks from the jury was a winnable issue. The International Labor Defense, an organ of the Communist Party, called the Crawford case "the worse betrayal that the NAACP leaders have ever perpetrated against the Negro masses.” Among radicals of the day, Houston had become an “Uncle Tom.” He felt compelled to defend the widespread criticism in print. In an article published in the Nation, he explained his decision not to appeal: Crawford “did not want to gamble with his life to further challenge the issue of jury selection” and, as Crawford’s counsel, Houston took his “orders from him.” Moreover, argued Houston, it was better to force the jury issue in a less sensational case that might “provoke the minimum amount of resistance.” Houston thought as a result of NAACP strategy, “race relations” in Virginia were “better than ever before.”

As Houston became more involved in NAACP work, he involved himself more in its internal controversies as well. W. E. B. Du Bois led a group within the organization that favored “voluntary segregation” as a solution to the problems black Americans faced in the 1930s. For Du Bois, there was no choice for the foreseeable future between segregation and no segregation, so efforts should be directed to organizing social and political power within the black community. Houston disagreed. In a speech before the NAACP’s 1934 annual conference, Houston argued that “if the Negro is to make any further progress” against “private prejudice and public administration” he “must unite with the poor white.” Houston saw the law as “a powerful weapon” that could be used to advance the cause of the economically disadvantaged classes. Even as he continued to be castigated by Communists and other radicals for his conduct of the Crawford case and for his strategy of attacking segregation gradually, Houston urged a strategy of cooperation with these same groups.

In the view of Houston, the case of the “Scottsboro Boys” called for a setting aside of differences with the ILD, who won the batter to defend eight black teenagers wrongly accused of gang raping two white women. He argued that the two organizations should work together to correct the awful injustice wrought by Alabama’s legal system. Houston and his law students participated in marches and sent financial contributions to the defense effort. Public support for the Scottsboro Boys—demonstrated in marches and protests from Berlin to Chattanooga—impressed Houston. He wrote that the case “caught the imagination of Negroes as nothing else within a decade.” Some voices within the NAACP condemned such tactics as showcasing the recanting complainant, Ruby Bates, at Scottsboro Boys’ rallies, but Houston disagreed. Houston said “she is now testifying before that jury that will ultimately dispose of the Scottsboro cases: that is, before the public opinion of the world.” Bates served, Houston said, as “a living example of the results of the oppressive system of the South by which the working classes white and Negro are set at each other’s throats in order to perpetuate the system of discrimination and exploitation.” Houston urged Walter White “regardless of differences between the NAACP and the ILD” to get the branches “to move, send telegrams, protests, etc.” Houston saw a larger benefit from the I.L.D.’s work on the Scottsboro case. He credited their efforts with making “it impossible for the Negro bourgeoisie in the future to be as complacent and supine before racial injustices as it was prior to Scottsboro."” Years later, Houston would call the Scottsboro case an “historic departure” that raised black consciousness and made African-Americans feel that “even without the ordinary weapons of democracy” they “still had the force” to change an oppressive system.

In October 1934, Houston recommended to the NAACP board that the organization concentrate its legal efforts on ending discrimination in education. The fight must begin, he argued, under the prevailing separate but equal principle announced in Plessy. Given the pervasive discrimination and economic deprivation in the United States, it was unrealistic to expect courts to jettison separate but equal immediately. Rather, the NAACP should work to make segregation with equality too expensive to maintain. It should seek to demonstrate beyond question the inequalities that exist in education—it should provide hard evidence of the salary differentials between black and white teachers and the limited opportunities that exist for black students compared to their white counterparts.

Houston’s proposed campaign to attack segregation in education impressed NAACP leaders, who appointed Houston special counsel. On a rainy summer night, Houston boarded a train in Washington, set to begin a new phase in his remarkable life. In the wee hours of July 11, 1935, Houston registered at the 135th Street YMCA in Harlem. The next morning he traveled to the NAACP national offices at 69 Fifth Avenue to take the first steps down the long road to overturning Plessy.

7

Slavery in the most northern of the slave states, Missouri, took a different form than in states farther south. Cotton was not king in Missouri; plantations were few and far between. Slaves worked on small farms, as cabin boys on riverboats, as domestics, in lead mines. Dred Scott of St. Louis, the most famous of all slaves, like most Missouri slaves, never worked a crop. Instead, typical of urban slaves, he performed odd jobs and errands for his master, a physician named John Sandford. Lower concentrations of slaves in Missouri meant less fear of slave revolts than in the plantation states. Consequently, Missouri—unlike the South, which feared that too much knowledge might inspire collective action—did not have laws on its statute books during the 1820s through early 1840s that prohibited the teaching of slaves. This did not mean, of course, that slaves received instruction even remotely similar to whites. In a frontier slave society, slaves could look only to the families of their slave masters for instruction. Some families taught their slaves how to read and write, but most did not. Slightly better opportunities for education existed in the urban areas of St. Louis and Kansas City. A few schools permitted slaves—provided that their owners agreed--to enroll for basic courses. In the late 1840s, however, this small opening to the world of books and learning closed. Amidst a growing concern about slave revolts, the Missouri General Assembly voted to prohibit schools from teaching slaves how to read or write.

After the Civil War, Missouri adopted a new Constitution that provided “separate schools may be established for the children of African descent.” Where such separate schools were established “funds provided in support…shall be in proportion to the number of children, without regard to color.” In the period of Reconstruction, Missouri built enough schools for blacks that it could be said that the “state has a higher proportion of schools for colored children than any former slave state.” Negroes in cities and larger towns attended segregated schools, but in rural areas, blacks often attended schools along with whites. After Reconstruction, however, black education became increasingly neglected. In 1889, the Missouri Assembly ended the practice of many of its rural school districts by passing legislation prohibiting racial mixing in the schools. Two years later, the Missouri Supreme Court, in Lehew v. Brummel, upheld the state’s order that rural Grundy County cease providing education in its integrated public school to four black students. The Court declared, “Color carries with it natural race peculiarities…some of which can never be eradicated.” The expense of building separate schools to accommodate a handful of blacks meant that the practical effect of the state’s ban on racial mixing was the complete elimination of educational opportunities for many rural blacks.

The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia contributed to a renewed interest in Negro education in the late teens. Many believed education to be the key to making the specters of “anarchy and bolshevism” less appealing to blacks. By the early 1920s, Missouri again could claim to be a leader among the seventeen former slave states in providing educational opportunities to blacks.

Despite improved opportunities for blacks in primary and secondary education, higher education in Missouri remained beyond the reach of all but a handful of blacks. Only one public college in the state, Lincoln University in Jefferson City, admitted blacks—and few that it admitted graduated. In 1916, Lincoln reported no graduates at all. In 1920, it reported eighteen. Although given a governing structure similar to that of the University of Missouri, Lincoln could not compete in either scope or quality of its course offerings. The legislative promise to “afford training to the Negro…up to the standard furnished at the University of Missouri” rang hollow.

8

From his post at the NAACP headquarters in New York, Charles Houston in 1935 planned his legal campaign to end segregation in public education. “Education is preparation for the competition of life,” Houston declared. For blacks to compete successfully, the biggest of all obstacles facing American blacks in the 1930s must be eliminated. His campaign would proceed in three steps. First, he would make plain the inequality that existed in the educational opportunities of blacks and whites. Second, he would make equality too expensive for states to maintain. Finally, he would attack the separate but equal principle upon which segregation rested. “His ultimate goal” was the “complete eliminate of discrimination.”

Houston opened his appeal for support of his campaign with the words of Frederick Douglass: “To make a contented slave you must make a thoughtless one,…darken his moral and mental visions, and…annihilate his power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery….It must not depend upon mere force; the slave must know no higher law than his master’s will.” As long as ignorance prevails, blacks will remain “tools” of the “exploiting class.”

As Houston saw it, whites claimed that the backwardness of blacks justified “poorer teachers, wretched schools, shorter terms and an inferior type of education.” The real reason was more insidious. “Discrimination in education is symbolic of all the more drastic discrimination which Negroes suffer in American life.” It was, he argued, the objective of whites to prepare blacks “to accept an inferior position…without protest or struggle.” According to Houston, the discrimination in education practiced against the black was “no accident.”

Before a frontal attack on segregation could be made, favorable precedents must be established. Big trees in the legal forest such as Plessy fell only when their roots became so weakened that they could no longer sustain the weight. Houston believed that the NAACP “cannot depend upon the judges to fight…our battles.” The campaign would be a long one. Blacks would have to unite behind it. Poor whites would have to be made to understand the justice of the blacks’ position and how their cause might advance common interests. The propositions put forward by the NAACP would have to be viewed not as Negro propositions, but as those of “all the poor people of this country, black and white alike.” According to Houston, “The social and public factors must be developed along with and, if possible, before the actual litigation commences.”

Houston chose to focus first on segregation in the graduate and professional schools of state universities. The complete absence of graduate and professional opportunities in many states made the inequality dramatic and impossible to dismiss. “Not a single state-supported institution of higher learning in anyone of seventeen states out of nineteen states” enforcing separation by law allowed a Negro ‘to pursue professional or graduate training at public expense.” The Border states of Missouri and Maryland bowed in the direction of equality by providing so-called “out-of-state scholarships” that provided tuition reimbursement for qualified blacks to attend integrated schools in neighboring states. Houston saw the continuation of segregation in professional schools as nothing less than a tax on blacks “to educate the future white leaders who are supposed to rule over” them.

Houston saw other reasons for beginning his attack on Plessy in the professional schools. First, professional schools could be the source of sorely needed black leaders. Second, judges—as products of professional schools themselves—could appreciate the consequences of the inequalities that indisputably existed. Third, opposition to integration of professional schools, affecting relatively small numbers of older students, threatened southern whites far less than did the immediate integration of primary and secondary schools.

Houston filed his first case on behalf of Donald Murray, a black graduate of Amherst College who wished to attend the University of Maryland Law School. The case came to Houston’s attention by way of his ex-student Thurgood Marshall, then a lawyer practicing in his hometown of Baltimore. Houston petitioned a Maryland state court to order the University of Maryland to accept Murray’s application and, if he met the general standards, admit him. After listening to Murray’s evidence and arguments, a Maryland district judge directed the University to admit Murray. The Maryland Court of Appeals in November 1935 affirmed the district court’s decision. An important precedent had been established, but the Murray decision had the force of law only in Maryland. To end segregation in the professional schools of other states, a case must be taken to the United States Supreme Court.

In an article entitled “Don’t Shout Too Soon,” Houston warned black Americans not to get overly excited by the Maryland result: “Lawsuits mean little unless supported by public opinion. Nobody needs to explain to the Negro the difference between the law in books and the law in action.” Houston wrote that “the walls of prejudice are not going to tumble down just because the Court of Appeals issued its solemn pronouncement.” He noted that the decision set off “fear among white students” that “a flood of Negroes” might enroll “and injure the standing of the University.” The future of black Americans, said Houston, depended upon educating white Americans about racial injustice. “As Negroes we have wrestled with the problems of discrimination so long that we have a tendency to feel that any person in the country knows those problems as well as we do.” To illustrate his point that they don’t, Houston noted: “In St. Louis last January the editor of one of the most influential dailies was shocked to learn that qualified Negroes were excluded from the state university.” We must, Houston urged his readers, send our message out to white America “ahead of rank reactionaries feeding them racial intolerance and hatred.”

9

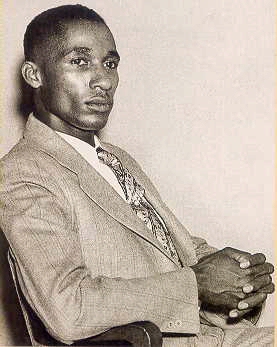

Lloyd Gaines

In June 1935, the Registrar at the University of Missouri, Silas Woodson Canada, received a request for a catalog from a prospective student living at 1000 Moreau Drive in Jefferson City. S. W. Canada responded as he had to hundreds of similar requests. Within a week, a form letter and a catalog were on their way to Lloyd L. Gaines.

Although neither Canada nor anyone else at the University of Missouri knew it at the time, Lloyd L. Gaines was black. Born in Mississippi in 1911, Lloyd at age fifteen moved with his family to St. Louis. Gaines proved himself to be a superior student. The tall, rangy, thin-faced youth graduated in three years from Vashon High School as the senior class president and valedictorian in a class of fifty. His entry in an essay competition, “U. S. Inspection of Meat,” won first place and earned him a $250 scholarship. Gaines used the scholarship to study for a year at Stowe Teachers College in St. Louis, then transferred to Lincoln University, Missouri’s all-black college, after it awarded him a another scholarship in 1933. At Lincoln as in high school, Gaines combined solid academic performance and an impressive schedule of activities. He joined the Negro social fraternity, attended the American Negro Economic Conference at Wilberforce University as Lincoln’s campus representative, and served at president of the 1935 class. He graduated in August 1935 with a major in History and minors in English and Education.

Gaines left Lincoln in the Depression year of 1935 with three impressive recommendations from his college teachers. His Education professor, S. F. Collins, wrote that Gaines “is conscientious, painstaking and is desirous of growing in the teaching field.” Cecil Blue of the English Department described Gaines as “an earnest young man who wants to get somewhere.” Sherman Savage, Gaines’ major supervisor from the History Department, believed “his resourcefulness and ingenuity will make him an excellent teacher.” Savage added that “his poise and temperment” should be “an asset in any community where he happens to work.” Despite the glowing praise from his professors, Gaines failed to find work as a teacher.

While Lloyd Gaines was looking for work, Charles Houston analyzed the prospects for a successful suit against the University of Missouri based on its policy of segregation. In July, Houston contracted with a black St. Louis attorney, Sidney R. Redmond, to prepare a “preliminary investigation and written report concerning the exclusion of Negroes from the University of Missouri.” Houston’s memorandum to Redmond requested him to investigate and compare rates of faculty compensation, course offerings, and budgets of the University of Missouri and its all-black counterpart, Lincoln University. Houston had more specific requests as well: “On the visit to Columbia, take camera along and take pictures of the buildings at the University which house departments for which there is no equivalent Negro education in the state.” Thinking ahead to the possible lawsuit, Houston asked Redmond to “obtain application for admission blanks.” But Houston warned Redmond to be careful: “These must not be obtained under subterfuge, because we want our hands to be absolutely clean. Best way here is to let the prospective student or some of his friends obtain the blank in his or her own way.” For his efforts, Redmond received fifty dollars plus expenses.

Within a few weeks of Houston’s memo to Redmond, in August 1935, Lloyd Gaines filled out an application for the University of Missouri Law School. At the same time, Gaines wrote to the president of Lincoln University informing him of his plans: “I am applying for admission to the Missouri University School of Law with no other hope than this initial move will ultimately rebound to increase the opportunities for intellectual advancement of the Negro youth.” Gaines also requested that the Registrar at Lincoln forward his transcript to the University of Missouri in Columbia. University lawyers later suspected Gaines to be a mere pawn of the NAACP with no serious desire to attend law school—a charge which Gaines and the NAACP publicly denied. It remains a mystery whether Gaines made his application on his own initiative or at the suggestion of the NAACP, although the timing of Houston’s memo and the application gives some credence to the University lawyers’ charge.

Application forms in 1935 did not ask applicants to identify their race. Only when the University of Missouri received Gaines’s transcript from Lincoln did officials realize that Gaines was black. Registrar S. W. Canada sent Gaines a telegram indicating that his application no longer was considered a routine matter: REGARDING YOUR ADMISSION TO LAW SCHOOL PRESIDENT FLORENCE AND MEMBER BOARD LINCOLN UNIVERSITY WILL CONFER THIS AFTERNOON IN JEFFERSON CITY ABOUT MATTER SUGGEST YOU COMMUNICATE WITH PRESIDENT FLORENCE REGARDING POSSIBLE ARRANGEMENTS AND FURTHER ADVICE. The same day that Gaines received the telegram, September 18, 1935, he wrote President Florence of Lincoln University. He asked Florence to let him know, by return mail, “just what are the POSSIBLE ARRANGEMENTS and FURTHER ADVICE.” President Florence responded five days later with the advice that Gaines take advantage of the Missouri law that made him eligible for a scholarship to attend law school at a neighboring state school that admitted blacks.

Gaines wrote instead directly to the President Frederick Middlebush of the University of Missouri. “I am a student of limited means but commendable scholastic standing,” Gaines wrote. “May I depend upon you to see that I am admitted to Missouri University, where I am sure of getting what I want at a cost that is most reasonable? An immediate reply would be highly appreciated.” President Middlebush never replied. Nor did the university formally admit or reject the application of Gaines. It merely sat there on a desk, a pile of one.

10

Houston initially believed that the Murray decision in Maryland might convince the University of Missouri not to contest Gaines’ admission. Houston seemed to be more concerned in early 1936 about making Gaines’ entry into the all-white student body as smooth as possible than in forcing his admission through a lawsuit. Houston knew Columbia’s history of racism. On July 28, 1923, a mob in Columbia—including University of Missouri students—lynched a black named James Scott. Scott also was a victim of inaction. Although the Governor learned of the impending lynching hours before it occurred, he chose not to call out the militia. With a view to this history, Houston wrote: “It is up to the Association, the citizens of Missouri, and the people of the United States to convince the Governor of Missouri, the President and Board of Curators of the University, and the student body, that regardless of what happened in 1923, there must be no violence when Lloyd Gaines arrives at the School of Law in 1936 or 1937. A broad sympathetic appeal for fair play must be made to the students of the University. Perhaps when students realize that Lloyd Gaines’ presence will not interfere with their ordinary routine and when they understand some of the hardships and handicaps which Negro boys and girls have had to face in order to get an education, the spirit of fair play will prevail.”

Soon, however, Missouri made it clear that it would not desegregate without a fight. Redmond’s report on the suitability of Missouri as a test case described in detail discrimination in higher education in Missouri and recommended that the NAACP take the Gaines case. Houston and a team of black lawyers from Missouri, Tennessee, Maryland, and Washington D. C. examined Redmond’s report. They considered the likelihood of successful litigation and compared it against other possible challenges from around the country. On January 24, 1936, the NAACP, on behalf of Lloyd Gaines, filed suit against the University of Missouri in Boone County Circuit Court in Columbia. The suit was in the form of a petition for a writ of mandamus asking the court to order Registrar S. W. Canada to either approve or reject Gaines’s pending application. From the Hotel Booker in Washington, Houston sent a telegram to NAACP President Walter White informing him of the action: “LLOYD L. GAINES AGAINST S. W. CANADA REGISTRAR NO OTHER DEFENDANTS FILED TODAY PAPERS IN MAIL SUGGEST SCHULYER TRY HAND AT SPECIAL ARTICLE FOR NEGRO PRESS WHEN PAPERS ARRIVE MONDAY.”

President Middlebush took the issue of Gaines’s suit to the Board of Curators the next month. The Board, turning to its lawyer members, requested a report on possible responses as soon as possible. When the Board reconvened, it followed the recommendation of its lawyers by adopting a resolution concerning the admittance of Negro applicants to the University. The resolution contained three “whereas paragraphs” outlining the facts as the Board understood them: “Lloyd Gaines, Colored, has applied for admission to the School of Law,” the “people of Missouri” have “forbidden the attendance…of a colored person at the University of Missouri,” and the Legislature has provided for “the payment, out of the public treasury, of the tuition, at universities in adjacent states, of colored students desiring to take any course of study not being taught at Lincoln University.” A fourth paragraph concluded “any change in the state system of separate instruction…would react to the detriment of both Lincoln University and the University of Missouri.” Accordingly, the Board resolved “that the application of Lloyd L. Gaines be and it hereby is rejected.”

The action of the Board rendered the NAACP’s request for a writ of mandamus moot. A new petition filed by Charles Houston, Sidney Redmond, and Henry D. Espy contended that the rejection of Gaines “solely on the basis of color was a clear violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution.” Lawyers for the University responded by arguing that the fault lay with Lincoln University, which failed to provide a law program for Negroes, and not with their client. Gaines, the lawyers suggested, sued the wrong party. After both parties filed briefs with the Boone County court, Judge W. M. Dinwiddie set the matter for trial on July 10, 1936.

Charles Houston arrived in St. Louis on July 6 to begin concentrated preparation for the Gaines trial. At 6:00 A.M. on a hot Friday, July 10, Houston, Gaines, and two other NAACP attorneys set out for the courthouse in Columbia. They arrived three hours later. Houston took his seat at the plaintiff’s table along with Gaines, Redmond and Espy. The three lawyers for the university, Registrar Canada, and President Middlebush, seated themselves at the defense table.

About 200 people crowded into the Boone County courthouse to view the proceedings. Houston had hoped for a large black turnout to demonstrate the importance of the case to Missouri’s African-American population. As Houston scanned the crowd, however, he saw more white faces than black faces. The heat (temperatures rose to over 100 degrees in the afternoon), the distance of Columbia from centers of black population, the lack of public transportation, and the fact that two blacks had recently been lynched in the Columbia vicinity reduced the number of black spectators. Many in the crowd were white farmers. A serious drought had hit central Missouri. Dozens of farmers had traveled to Columbia to seek relief from county welfare agencies located in the courthouse. When the relief lines got too long, farmers wandered into the courtroom to observe the rare spectacle of Negro lawyers performing. In addition to the farmers, about one hundred law students from the University of Missouri came to learn about the case that had put their school in the news.

Houston noted that blacks and whites sat together in the courtroom. No “whites only” or “colored” signs hung on restroom doors or water fountains. Missouri practiced selective—not pervasive—segregation.

Sidney Redmond opened the hearing with a factual statement of the case for Lloyd Gaines. William Hogsett of Kansas City, responded with an opening statement for the university. Addressing the press table more than the judge, Hogsett in a dramatic and driving style called the ambition of Gaines to attend law school “laudable.” Gaines, in fact, had every right to a legal education—but not at the University of Missouri, which for one hundred years had been an all-white institution. Gaines had no claim against the University of Missouri. He should apply to Lincoln and hope that they will see fit to add a law program.

When Judge Didwiddle said, looking toward the plaintiff’s table, “Call your first witness,” Lloyd Lionel Gaines stood and walked to the stand. After a few introductory questions, Redmond asked Gaines, “Have you made up your mind as to what you wish to do with your life?” “I wish to practice law,” Gaines replied. “To what schools have you made application?” “I have made application only to the University of Missouri,” Gaines answered. Redmond asked Gaines why he chose not to accept Missouri’s offer of a scholarship to attend an out-of-state law school. Gaines gave his reasons: Missouri was “a very good law school,” it was cheaper “taking into account the facts of transportation and communication,” it was “nearer home…if I wanted to make a fast trip home and back,” and it emphasized Missouri law that would help fulfill his “wish to practice law here within the state of Missouri.” Asked if he would obey the rules of the University were he to be admitted, Gaines answered, “Yes, sir.”

Defense attorney Hogsett tried to portray Gaines as someone more interested in helping the NAACP than going to law school. He suggested Gaines should have applied to all-black Lincoln University, even though it had no law program. He asked Gaines whether he had “ever seen a colored student in Missouri University,” suggesting that he knew—and may even have hoped—that his application would be denied. Hogsett demanded to know whether “within two days” after receiving his denial he “was in communication with the NAACP.” Did “these gentlemen now representing you” advise you “to bring this suit?” Hogsett wondered. “No, that is my idea—about this suit,” Gaines replied. What’s wrong with going to law school in Iowa, Hogsett asked. Gaines pointed Hogsett to a paragraph in the Iowa Law School catalog that promised “special attention to the needs of the residents of Iowa, for the practice of law within Iowa.” Hogsett asked Gaines about his refusal to answer, in an earlier deposition, a question about his willingness to attend Lincoln University if it offered a good law program. “You refused to answer, didn’t you?” he stated more than asked. Hogsett ended his cross-examination with a simple question, “Mr. Gaines, did you believe that Negroes were barred from attending the Law School of the University of Missouri?” The answer of Gaines could not have been honest: “No sir, I did not.”

Charles Houston next called Missouri Law Dean William Masterson to the stand. Houston’s main purpose in calling Masterson—obviously an unfriendly witness—was to use him to show the benefits to Gaines of legal education at the University of Missouri. Somewhat disingenuously, Masterson claimed a legal education is a legal education, regardless of what school it comes from. Houston suggested to Masterson, “you pay particular attention to Missouri decisions and Missouri law, do you not?” “We do not,” Masterson replied. Houston pointed to the Law Review’s policy of including at least one article on Missouri law in each issue as evidence that the school emphasized Missouri law. Masterson continued to assert that Gaines could do just as well in Iowa City, Champaign, Lincoln, or Lawrence—they all use the same casebooks, they all cover the same law. Masterson even contended that Gaines might get a better education at a new all-black law school: “you would get a lot more” opportunities to participate in class discussions “with two or three students in the class.” Houston asked, “But if you had only one student, wouldn’t you lose all that?” Masterson thought getting information “directly” would be more “time-saving.” Besides, he concluded, “you know yourself, when you were in the Harvard Law School, a great many questions were sheer nonsense.” Houston rejoined, “But sometimes it was the ‘nonsense’ that made you learn, wasn’t it?” Judge Didwiddle broke in: “Well, let’s get along. The Court is pretty well informed on that.” Later, Charles Houston recalled his encounter with Missouri’s Law Dean: “Masterson wiggled like an earthworm…and made just about the sorriest and most pitiable spectacle.” Houston called Masterson’s inability to provide details concerning the Law School’s admission process or its budget, “the most complete lapse of memory” he had “ever witnessed.”

Silas Woodson Canada, the Registrar of the University of Missouri, was Houston’s next witness. Houston demonstrated that discrimination at the Univeristy of Missouri was exclusively racial. “Did you admit Chinese student?”—Yes, sir. “Japanese students?”—Yes, sir. “Hindu students?”—Yes, sir. “The only students you bar would be students of African descent, is that right?” Canada admitted, “Other things being equal, I think so, yes, sir.”

Houston filled in his case with the brief testimony of three other witnesses. He called T. D. Stanford, the University’s fiscal manager, to show that law schools have large budgets, many employees, and are not likely to sprout up overnight. Robert Witherspoon, a black lawyer from St. Louis, testified concerning the racial make-up of the Missouri bar. Witherspoon said that of the forty-five black lawyers in Missouri, all but one lived in St. Louis or Kansas City. Most of the forty-five were “old practicioners.” Only “about three” Negroes had joined the Missouri bar in the previous five years. Houston called Joseph Elliff, a member of State Board of Curators, to the stand to show that Missouri had neither a current plan nor money for the development of a law program at Lincoln University. Eliff, asked by Houston whether he believed Lincoln qualified as a true university, called the all-black school “an embryo university.”

The defense employed several well-known Missouri figures to buttress its case. N. T. Gentry, a former judge and Attorney General, took the stand to agree the segregated education was “the settled policy of this state ever since you have known it.” F. M. McDavid, state senator and President of the University of Missouri, testified that the University, in turning down the application of Gaines, was just doing its duty under state law. Hogsett asked McDavid, “What would be the effect of the admission of Negroes into the University of Missouri?” McDavid answered, “I think it would create a great amount of trouble.” McDavid continued, “it would make discipline difficult” and undermine “the traditions of this city and school, running through nearly a hundred years.” Houston, cross-examining McDavid, wanted to know whether “a hundred years tradition” could “bind progress forever?” Responding to Houston’s questions, McDavid said he believed the state would fulfill its duty to Gaines, even if it meant creating a new program. Houston replied, “They give Negroes a piece of paper, while the white citizens have an actuality.” Houston asked McDavid if he was “familiar with the fact that a Negro boy was granted admission to the School of Law of the University of Maryland.” McDavid allowed, “I think so.” “Did you make any investigation, in considering the Gaines case, to find out whether any disciplinary problems had arisen at the University of Maryland?” McDavid conceded that he had not. Houston wondered what led him to think the presence of a Negro would cause problems? McDavid, saying he “talked with a good many students about this,” said that it would be “a most unfortunate thing,--an unhappy thing.” “I don’t think [Gaines] would be happy and I don’t think the other crowd would be happy.”

Two weeks later, Judge Didwiddle issued his decision dismissing the petition of Gaines. The judge gave no reasons for his conclusion. The decision came as no surprise to Houston, who had already written in a memorandum to the New York office, “It is beyond expectation that the court will decide in our favor.” Houston announced that the decision would be appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court.

11

The Depression wreaked havoc with Houston’s ambitious plans to challenge segregated schools. Houston complained, “The NAACP is so poor that it has to strain to the utmost to find even enough money for primary court expenses.” The Garland Fund, the source of most of the revenues for the legal campaign, was severely depleted. In October, Houston received a memo from the NAACP’s financial director that warned that the Gaines case might have to be dropped: “This is clearly an instance of a case that will have to be abandoned. This case cannot be taken to the Supreme Court without additional funds.” Houston would not let that happen. He would find other ways of trimming his office’s already tight budget.

The Gaines case presented Houston with other problems. The considerable work Houston put into Gaines and other education cases in the early stages of litigation made it impossible for him to keep up with the other legal work of the NAACP. Houston wrote Thurgood Marshall: “The Association needs another full-time lawyer in the national office. I am not only a lawyer but evangelist and stump speaker…I don’t know of anybody I would rather have in the national office than you.” Following Houston’s recommendation, the NAACP Board voted in October 1936 to make Thurgood Marshall Assistant Special Counsel.

Charles Houston arrived in St. Louis on December 11, 1936, checking into the Hotel Washington. The next day he travelled to Jefferson City to argue Gaines’s appeal before the Missouri Supreme Court. Normally, one of two Divisions of the Court considered appeals. Because of the importance of the Gaines case, all justices of the Court heard his appeal.

Houston argued that the refusal to admit Gaines to the University of Missouri violated his rights under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Neither “the slender hope” that Gaines might someday attend a new law program at Lincoln nor the provision of tuition scholarships to attend an out-of-state law school met the Constitution’s requirement of equal treatment regardless of race.

Two months later a unanimous Missouri Supreme Court affirmed Judge Dinwiddie’s decision. Justice Frank’s opinion repeated language from an earlier Missouri decision: “There are differences in the races” that “create different social relations recognized by all well-organized governments.” Separate school for blacks “is to their great advantage.” Missouri did not violate the separate-but-equal principle of Plessy: “Equality is not identity of privileges.” Gaines can be adequately prepared for Missouri practice in an out-of-state school. His added travel costs to out-of-state schools “furnishes no substantial ground for complaint.” Justice Frank concluded for the Court: “[W]e hold that the opportunity offered appellant for law education in the university of an adjacent state is substantially equal to that offered white students by the University of Missouri.”

With the decision of the Missouri Supreme Court, the case of Gaines became the right challenge at the right time. The NAACP petitioned the United State Supreme Court to consider the Gaines appeal.

In the summer of 1938, Charles Houston began preparations for the most significant challenge to segregated education since Charles Sumner presented his arguments to the Massachusetts Supreme Court in the Roberts case almost a century earlier.

12

The Supreme Court in 1938 was a more moderate Court than the one that just three years earlier had President Roosevelt devising his “court-packing” plan. Roosevelt had made two appointments in the previous fifteen months. One of the new appointees, Hugo Black, would become a leading voice on the Court for civil liberties for decades to come. The other recent addition to the Court, Stanley Reed, though hardly a champion of civil rights, represented at least a winnable vote.

Moreover, the Supreme Court had issued landmark decisions over the past six years upholding the claims of black litigants. None of these recent decisions attracted more attention, of course, than those rendered by the Court in two appeals in the Scottsboro Boys cases. As Houston prepared in the fall of 1938 to argue the Gaines case, he had reasons to be cautiously optimistic.

On November 8, 1938, Houston reread the record in Gaines. He made notes on issues to stress and honed his arguments. Then he walked from his office on F Street to the Howard Law School where he rehearsed his oral argument before students and professors. Two members of his audience, Robert Carter and Spottswood Robinson, would later be among the first blacks to serve on the federal bench. After Houston completed his argument, he asked his audience to critique him.

The next day, before eight justices of the Supreme Court—a replacement for the recently deceased Justice Cardozo had not yet been made--Charles Houston argued the case on which the hopes of so many black lawyers had been fastened.

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes announced the Court’s decision in Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, Registrar of the University of Missouri on December 12, 1938. The Missouri Supreme Court had erred. Missouri had violated the right of Lloyd Gaines to the equal protection of the laws. “The equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws,” Hughes declared. “The obligation of the State to provide the protection of equal laws must be performed…within its own jurisdiction.” “The essence of the constitutional right is that it is a personal one.” Gaines “as an individual” was entitled to have Missouri “furnish within its borders facilities for legal education substantially equal to those which the State afforded for persons of the white race, whether or not other Negroes sought the same opportunity.”

Justices Pierce Butler and James McReynolds dissented. They concluded that the Missouri Supreme Court “well understood the grave difficulties of the situation and rightly refused to upset the settled legislative policy of the State.” The two dissenters predicted that Missouri might, in response to the Court’s decision, “abandon her law school and thereby disadvantage her white citizens without improving petitioner’s opportunities for legal instruction.” Or they wrote, Missouri might choose to integrate her law school and “as indicated by experience, damnify both races.”

Charles Houston told the press that Gaines would open up new opportunities for blacks in the sixteen states that barred them from professional schools. He said the decision “completely knocked out as a permanent policy” the practice of a state paying tuition for blacks to attend schools in other states instead of providing them an education within its own borders. Many black commentators were less restrained than Houston. One called the decision “the greatest victory Negroes had won since freedom.” More than being a decision just about Missouri’s unique approach to race and higher education, the Gaines case established the principle of equality of education.

Lloyd Gaines learned of the Court’s decision in Lansing, Michigan, where he was working for the Michigan civil service department on a compensation survey. He declined comment except to say he would confer with his attorneys before making any plans.

13

Northern papers praised the Supreme Court’s decision in the Gaines. The New York Times declared, “Once more the Supreme Court has spoken out in defense of equality of human rights.” The Philadelphia Bulletin saw the decision as establishing for the black “that equality before the law which dictatorship flouts but which is the life-breath of democracy.” The Iowa City Iowan stated “The surprising thing is not the nature of the decision, but the fact that such a decision actually had to be made affecting a neighboring university.” The editorial in The Iowan expressed pleasure “that the University of Missouri’s absurd self-assurance has been so realistically punctured.” Black papers joined the chorus of praise for the decision. An editorial in the Kansas City Call declared: “If keeping the races separate is so important to Missourians that coeducation is unthinkable, then let them count the cost! Because Negroes will accept no make shifts, no postponements, no evasions!”

Southern papers, on the other hand, worried over what Gaines might mean for their own state universities. The Fort Worth Star Telegram urged states to provide opportunities for blacks “in the form of annexes to state universities or enlargement of existing Negro colleges.” The Charleston News and Courier, on the other hand, expressed the view that the decision would lower standards and reduce higher education in the South “to a lowly estate in public opinion.” The paper urged the State to consider adopting, for the first time, entrance examinations as a means of keeping blacks out of all-white institutions.

The Missouri Student, a paper edited by students at the University of Missouri, offered an interesting editorial comment:

It is apparent that the state will employ every trick in its hand to maintain its traditional policy of separation of whites and Negroes in schools. At the same time it is fighting an uphill battle that measures as high as all the states who allow the Negro to mix with the white in educational institutions, American tradition of racial equality, and topping it all, the written constitution. The hill is steep, and rugged, and the fight looms as a losing battle.Of immediate importance to students is the possibility of Gaines occupying a seat in a Missouri University classroom. The law students were convinced Monday that Gaines would be “treated like a dog”—if he entered. Outspoken students said they would not sit by a Negro in class. Stronger voices announced that they would leave school, if Gaines were admitted. Where would they go? The Supreme Court decision holds for the nation; consequently, all southern schools will be forced to allow whites and Negroes to study in the same institution….

We who are students will have no say as to what will be done about the Negro attending school, but it is we who will go to school with him. Few will have the money to come, and those who do will come mostly for advanced education and, for the most part, will be a superior Negro.

Our actions in accepting him will define our status as Americans. Our pilgrim, continental, Gettysburg tradition is freedom and racial equality for all. It is our cue to pioneer the nation out of this last frontier of racial prejudice and superstition.

Hopes that Missouri would now consent to enroll Gaines in the University of Missouri School of Law soon faded. John D. Taylor, a lawyer from Keytesville in an area of Missouri known as “Little Dixie,” introduced a bill in the Missouri legislature designed to postpone integration of the University. Taylor, a thirty-year veteran of state politics and chairman of the House appropriations committee, proudly called himself “an unreconstructed rebel.” He referred to Negro constituents in his Chariton County as “my darkies.” Black students in his county, thanks in part to his effort to defeat appropriations for better facilities, attended school in a dilapidated, unpainted, framed two-room shack with scarred sixty-year-old desks and no indoor plumbing. White students, meanwhile, enjoyed a spacious brick school building with a spanking new gymnasium.

Taylor’s proposal, House Bill No. 195, authorized Lincoln University to “establish whatever graduate and professional schools are necessary to make Lincoln University the equivalent of the University of Missouri.” To accomplish this lofty goal, Taylor proposed appropriating only $200,000—and that out of so-called “special funds” that past experience had proven to be chimerical. Negroes denounced the Taylor bill as “subterfuge” and “an affront to the Supreme Court.” One black writer asked skeptically, “Missouri has the best journalism school in the country—could it be duplicated?” Thousands of blacks signed petitions urging a “no” vote on the Taylor bill. Carloads of blacks from Kansas City traveled to Jefferson City to voice their opposition at a hearing on the bill. Lucille Bluford, writing in Crisis magazine, observed that “nothing has tended to unify the race like the effort to defeat the Taylor bill.” A few whites offered their protests as well. A theology professor told legislators, “I feel a sense of shame that it was necessary for a group of people of one race to have come down here and show us how to treat them. Despite the efforts of black citizens and their white supporters, the Taylor bill passed the House 102 to 19, the Senate 25 to 6, and was signed by the Governor.

The Lincoln Board of Curators ordered Lincoln’s president to have a law school up and running and ready for Lloyd Gaines by September 1, 1939. The Missouri Supreme Court sent the Gaines case back to Boone County Circuit Court to determine whether the planned law school at Lincoln would comply with the U. S. Supreme Court’s requirement of “substantial equality.” Lincoln, meanwhile, made plans to open its law school. The University rented a building in St. Louis, hired a faculty of four, brought in a dean from Howard, and purchased a law library of 10,000 volumes. On September 21, the Lincoln Law School opened with thirty black students. Lloyd Gaines was not among them. A St. Louis organization called the Colored Clerk’s Circle formed a picket around what they denounced as the “Jim Crow” school.

Charles Houston and other NAACP attorneys assembled in early October 1939 to take depositions in preparation for the hearing scheduled a week later in Columbia to determine whether the University had complied with the Gaines decision. Attorneys deposed each of the four instructors of the new Lincoln Law School. The deposition of Lloyd Gaines was next. Attorneys planned to ask Gaines whether he considered Lincoln to be as good of a law school as Missouri and whether he planned to enroll there. Called for questioning, Gaines did not respond. He could not be located anywhere.

The NAACP enlisted the help of the nation’s press. Newspapers around the country ran his picture. People knowing his whereabouts were asked to call his attorneys. No news.

Lawyers for the University of Missouri warned that if Gaines could not be found soon, the case would have to be dismissed.

15

Shortly after the Supreme Court decision, Lloyd Gaines left his civil service job in Michigan and returned home to St. Louis, arriving on New Year’s Eve, 1938. He told friends that he intended to remain there until September, when he planned to begin school in Columbia. In the meantime, to pay the bills, he took a job as a filling station attendant.

On January 9, Gaines spoke to the St. Louis branch chapter of the NAACP. He told them that he stood “ready, willing, and able to enroll in the law department of the University, and had the fullest intention of doing so.”

Gaines quit his gas station job. He explained to his family that the station owner substituted inferior gas and he could not—in good conscience—continue to work there. Lloyd’s mother, Callie Gaines, recalled that her son “left here to go to Kansas City to make a speech. That’s the last I saw of him.” Gaines spoke at the Centennial Methodist Church. While in Kansas City, Gaines looked for work, but not finding any, boarded a train for Chicago, telling people in Kansas City that he would spend a few days there and then return to St. Louis.