Esther Brown

In 1948, Esther Brown, a 30-year-old Jewish housewife in Merriam, Kansas (a suburb of Kansas City), began a fight for racial justice in a Kansas school district. Shocked by the condition of an all-black school in the South Park neighborhood of her African-American maid, Brown took her complaints to the all-white school board, which was then supporting a bond issue for a well-equipped new school for whites. The school board seemed unmoved by the fact that students at the all-black, 88-year-old, two-room Walker School had to use an outhouse on the dirt playground, walk home for lunch, and attend a school with no principal and just two teachers. The board's concession to install new light bulbs caused Brown to leave the meeting feeling "nauseated." Esther grew increasingly active in the fight for better schools for African-Americans. She organized meetings of African-American parents and tried to convince white parents to join her cause. "I know none of you would want your children educated under such circumstances," she told a crowd of 350 at a meeting at the new white school. "They're not asking for integration--just a fair shake." Faced with intransigence, Esther asked the Kansas City, Kansas chapter of the NAACP to file suit, and then raised money for the legal battle, making pitches at a Billie Holliday concert and anywhere else she thought she might find supporters. Dissatisfied with her first counsel, she fired him, and hired black Topeka attorney Elisha Scott to pursue the case against the South Park district. As the suit progressed, Brown helped organize a boycott of the all-black school, and set up new private schools to educate the students instead. Brown paid a price for her activism. She was threatened, a cross was burned in her yard, and her husband fired from his job. In 1949, the Kansas Supreme Court, in Webb vs School District No. 90, held that blacks had the right to attend the new, previously all-white, South Park school. Esther's next target was Topeka, where she assisted in an effort that had been launched by the NAACP to integrate the city's elementary schools. Lucinda Todd, Secretary of the Topeka branch, years after the Brown v Board of Education decision said of Esther Brown's involvement: "I don't know if we could have done it without her." Esther Brown died in 1970. In 1975, a new public park in Merriam, Kansas, across from the site of the former all-black school, was dedicated in her honor. |

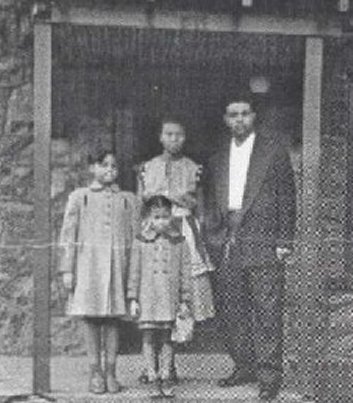

Oliver Brown and family

The Brown of Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka is Oliver Brown. Oliver Brown and his daughter, Linda, are remembered today, while the thirty-three plaintiffs, including thirteen parents and twenty children are largely forgotten, simply because Oliver Brown was listed first in the complaint. Had Oliver not agreed to participate in the suit, students today might talk of the famous case, say, of Carper v Board of Education or Fleming v Board of Education (two of the other adult plaintiffs who challenged Topeka's policy). Oliver Brown became involved in the case after being asked to become a plaintiff by attorney Charles Scott, an old childhood friend. Oliver Brown, 32 at the time the suit against the school district was brought, served as an assistant pastor at Topeka's black Methodist church and as a welder for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway. A former teacher described Brown as "an average pupil and a good citizen." Shy, hard-working, religious, and clearly no militant, Brown became the non-threatening face of the lawsuit. Brown and his wife had three children, ages 8, 4, and 5 months at the time of trial. Linda Brown attended all-black Monroe Elementary, a school located 21 blocks from their home on West First Street. Oliver Brown testified that "many times [Linda] had to wait through cold, the rain, and the snow" for a bus to take her to Monroe, even though the family lived only seven blocks from an all-white elementary school. Oliver also testified that Linda's route to her bus stop took her over a "main thoroughfare...with a vast amount of traffic." By the time the Supreme Court announced its decision in Brown, and the Topeka schools desegregated, Linda had moved on to a previously integrated junior high school. Linda's siblings, however, enjoyed the benefits of a desegregated elementary school education. Oliver Brown and his family moved to Springfield, Missouri in 1959 where he served as a minister. He died of a heart attack in 1961. |

Meet the Browns: Esther Brown And The Oliver Brown Family

- Details