In May, 1868, the Senate came within a single vote of taking the unprecedented step of removing a president from office. Although the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson was ostensibly about a violation of the Tenure of Office Act, it was about much more than that. Also on trial in 1868 were Johnson's lenient policies towards Reconstruction and his vetoes of the Freedmen's Bureau Act and the Civil Rights Act. The trial was, above all else, a political trial.

Andrew Johnson was a lifelong Democrat and slave owner who won a place alongside Abraham Lincoln on the 1864 Republican ("National Unity") ticket in order to gain the support of pro-war Democrats. Johnson was fiercely pro-Union and had come to national prominence when, as a senator from the important border state of Tennessee, he denounced secession as "treason."

On April 11, 1865, Abraham Lincoln gave his last major address. Lincoln congratulated Lee on his surrender, announced that his cabinet was united on a policy of reconstructing the Union, and expressed the hope that the states of the Confederacy would extend the vote to literate negroes and those who served as Union soldiers. Then came the tragic events at the Ford Theater.

Andrew Johnson became president. He was manifestly unfit for the office. Johnson was bullheaded and a narcissist. He would sometimes launch into drunken harangues. But it was Johnson's racism that presented the greatest threat to the Republic. Johnson said, "This is a country for white man, and by God as long as I am president it will be government for the white men." During his three years in office, Johnson largely tried to make good on that promise, undermining efforts to secure rights for African Americans in every way he could. Johnson pardoned Confederates and appointed numerous traitors to the Union cause to positions of power throughout the South. The predictable result was a resurgence of white supremacy in the states of the old Confederacy. Former Confederates, holding important local positions such as sheriffs, beat black freedmen and arrested them on trumped up charges. Massacres of dozens of former slaves and some white Republicans in places such as New Orleans and Memphis brought only a shrug from Johnson.

Johnson took issue with the Congress's insistence that seceding states ratify the Fourteenth Amendment as a ticket back to having full representation in Congress. Johnson's idiosyncratic view was basically that secession was illegal and so it never really happened and the southern states should therefore be welcomed back unconditionally. Consistent with his racist views, Johnson would veto bill after bill passed by the Republican Congress to help secure and protect the rights of southern slaves.

One could make a strong argument that Johnson's efforts to betray the cause of the Civil War and thwart the efforts of Congress to protect a class of Americans was a "high crime" and, therefore, an impeachable offense. That would have made for an impeachment trial that turned on America's ideals. It would have been an impeachment trial that went to the heart of the matter. But, instead, the impeachment trial would turn on a narrower question. The question of whether Johnson's firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, in violation of a law passed by Congress, rose to the level of an impeachable offense.

Events Leading to Impeachment

Interestingly, some Republicans in Congress believed, after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, that efforts to improve the lives of the newly freed slaves would actually increase. These Republicans in Congress, those most opposed to what they saw as the too-lenient policies of Lincoln toward reconstruction, thus saw Johnson's ascension as a hopeful sign. One of the radical Republicans of the Senate, Benjamin Wade, expressed his support: "Johnson, we have faith in you. By the gods, there will be no more trouble in running the government." Less than three years later, Wade would cast a vote to convict Johnson in the impeachment trial that nearly made him the next president of the United States.

There were two contending theories in post-war Washington concerning reconstruction. One theory argued that the states of the United States are indestructible by the acts of their own people and state sovereignty cannot be forfeited to the national government. Under this theory, the only task for the Federal Government was to suppress the insurrection, replace its leaders, and provide an opportunity for free government to re-emerge. Rehabilitation of the state was a job for the state itself. The other theory of reconstruction argued that the Civil War was a struggle between two governments, and that the southern territory was conquered land, without internal borders-- much less places with a right to statehood. Under this theory, the Federal Government might rule this territory as it pleases, admitting places as states under whatever rules it might prescribe.

Andrew Johnson was a proponent of the first, more lenient theory, while the radical Republicans who would so nearly remove him from office were advocates of the second theory. The most radical of the radical Republicans, men like Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner , believed also in the full political equality of the freed slaves. They believed that black men must be given equal rights to vote, hold office, own land, and enter into contracts, and until southern states made such promises in their laws they had no right to claim membership in the Union. (Republicans also had more practical reasons to worry about Johnson's lenient reconstruction policy: the congressmen elected by white southerners were certain to be overwhelmingly Democrats, reducing if not eliminating the Republican majorities in both houses.)

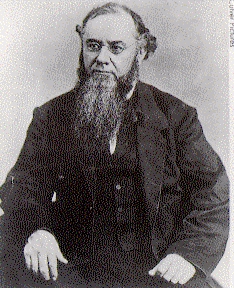

Thaddeus Stevens

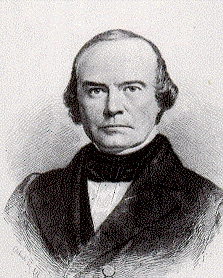

Senator Charles Sumner

In the spring of 1867, the new Congress passed over Johnson's veto a second Freedmen's Bureau bill and proposed to the states a Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution. (The Fourteenth Amendment is best known today for its requirement that states guarantee equal protection and due process of law, but the most controversial provisions of the time concerned the conditions precedent that imposed on states for readmission to the Union.) Johnson announced his opposition to the Fourteenth Amendment and campaigned for its defeat. The Reconstruction Act of 1867, also passed over a presidential veto, wiped out the "pretended state governments" of the ten excluded states and divided them into five military districts, each commanded by an officer of the army. To escape military rule, states were required to assent to the Fourteenth Amendment, frame a new constitution with delegates chosen without regard to color, and submit the new constitution to the Congress for examination. Johnson's message vetoing the Reconstruction Act was angry and accusatory, calling the act "a bill of attainder against nine million people at once" and suggesting that it reduced southerners to "the most abject and degrading slavery." Impeachment efforts in the House intensified, but the doubtfulness of conviction in the Senate, due in part to the knowledge that removal of Johnson would elevate to the presidency the less than universally popular Ben Wade, President Pro Tempore of the Senate, convinced many in the House to hold their fire. Representative Blaine spoke for a number of conservative Republicans when he said he "would rather have the President than the scallywags of Ben Wade."

Senator Benjamin Wade

The issue that finally turned the tide in favor of impeachment concerned Johnson's alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act. The Tenure of Office Act, passed in 1867 over yet another presidential veto, prohibited the President from removing from office, without the concurrence of the Senate, those officials whose appointment required Senate approval. The Act was passed primarily to preserve in office as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a holdover from the Lincoln Administration, whom the radical Republicans regarded "as their trusty outpost in the camp of the enemy." Although Stanton for many months largely acquiesced in Johnson's reconstruction policies, by June of 1867, his opposition was out in the open.The Department of War, under Stanton, occupied and administered military zones in the states fo the former Confederacy, until such time as they established biracial governments and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. Although in theory the Department of War was under the President, in the years following the Civil War it acted more as an independent organization enforcing the wishes of Congress agains the wishes of the president.

Johnson saw the situtation as nothing short of a mutiny. By July, Johnson was close to convinced that Stanton must go, Tenure of Office Act or no Tenure of Office Act. The final straw appears to have been the revelation on August 5, 1867, during an ongoing trial of Lincoln assassination conspirator John Surratt that Stanton two years earlier had deliberately withheld from Johnson a petition from five members of the military commission that convicted Mary Surratt urging that her death sentence be commuted to imprisonment. Stanton, Johnson believed, had hood-winked him into signing the death warrant of a woman who he most likely would have spared. That day Johnson sent Secretary Stanton the following message: "Sir: Public consideration of high character constrain me to say that your resignation as Secretary of War will be accepted." Stanton answered "that public considerations of a high character...constrain me not to resign." The Tenure of Office Act allowed the President to "suspend" an officer when the Congress was out of session, as it was at the time, so the President responded by suspending Stanton and replacing him with war hero Ulysses S. Grant.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

In January of 1868 the returning Senate took up the issue of Johnson's suspension of Secretary Stanton, and voted 35 to 6 not to concur in the action. On January 14, a triumphant Stanton marched to his old office in the War Building as the President considered his next move. Johnson was anxious to challenge the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act in court, but to do so he would have to replace Stanton and defy the Senate. This he did on February 21, 1868, naming as the new Secretary of War Major General Lorenzo Thomas. When Stanton notified his Capitol Hill allies of the presidential order to vacate his office, he received from Senator Sumner a one-word telegram: "Stick." Stick he did. When Thomas went to the War Department Building to claim his new office, Stanton refused to budge. After an awkward confrontation, the two men enjoyed a bottle of liquor together before Thomas finally headed home. For the next ninety days, Stanton would remain barricaded in his office.

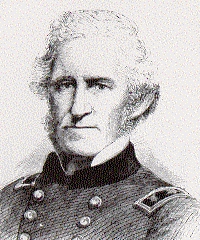

Lorenzo Thomas

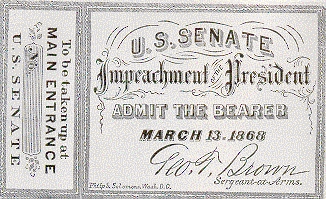

The Lorenzo Thomas appointment made impeachment in the House for violation of the Tenure of Office Act and other "high crimes and misdemeanors" inevitable. On February 24, the House voted to adopt an Impeachment Resolution by a vote of 126 to 47. Five days later, formal articles of impeachment were adopted by the House.

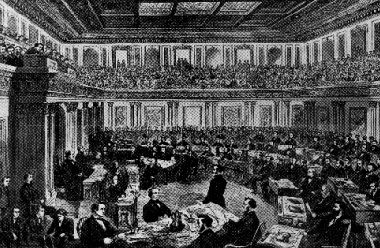

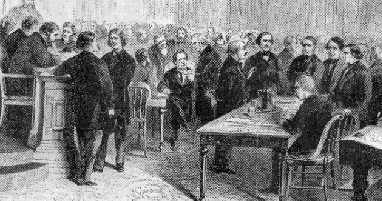

On March 30, 1868, Benjamin Butler rose before Chief Justice Salmon Chase and fifty-four senators to deliver the opening argument for the House Managers in the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson. Historians such as David Dewitt have been struck by the improbability of the scene: "The ponderous two-handed engine of impeachment, designed to be kept in cryptic darkness until some crisis of the nation's life cried out for interposition, was being dragged into open day to crush a formidable political antagonist a few months before the appointed time when the people might get rid of him altogether." Butler's three-hour opening argument was "a lawyer's plea with a dash of the demagogue." He contemptuously dismissed arguments that the Tenure of Office Act didn't cover Stanton, read parts of Johnson's 1866 speeches that were the basis of the tenth article of impeachment, and referred to the President as "accidental Chief" and "the elect of an assassin." (Butler was a poor choice for manager. His disrespectful treatment of the President damaged the prosecution's case with wavering senators and, in general, he made key strategic errors.)

Board of Impeachment Managers

House Managers proceeded to introduce documentary evidence and witness testimony supporting the eleven various articles of impeachment. Two witnesses described the confrontation between Edwin Stanton and Lorenzon Thomas in the War Office on the day of Stanton's firing, February 22. One witness brought on torrents of laughter by his description of his meeting with Thomas in the East Room of the White House when he told Thomas "that the eyes of Delaware were upon him." Several witnesses testified as to details concerning speeches by the President delivered in Cleveland and St. Louis in September of 1866. On Thursday, April 9, the Managers closed their case. Many observers concluded that the testimony added little to the Manager's case, and may have actually hurt their case by emphasizing the President's isolation and powerlessness in the face of a hostile Congress.

The opening argument for the President was delivered by Benjamin Curtis, a former justice of the Supreme Court best known for his dissent in the famous Dred Scott case. Curtis argued that Stanton was not covered by the Tenure of Office Act because the "term" of Lincoln ended with his death, that the President did not in fact violate the Act because he did not succeed in removing Stanton from office, and that the Act itself unconstitutionally infringed upon the powers of the President. As for the article based on Johnson's 1866 speeches, Curtis said "The House of Representatives has erected itself into a school of manners...and they desire the judgment of this body whether the President has not been guilty of indecorum." Curtis argued that conviction based on the tenth article of impeachment would violate the free speech clause of the First Amendment.

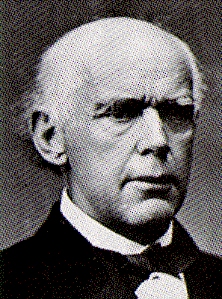

Senator Benjamin Curtis

Counsel for the President called only two witnesses of real consequence. Lorenzo Thomas , Johnson's would-be Secretary of War, was sworn in as a witness for the President and examined by Attorney General Stanbery concerning his encounters with Stanton. According to Thomas's testimony, the two were surprisingly cordial after Stanton had Thomas arrested, at one point sharing a bottle of whiskey together. Secretary Welles was called for the purpose of testifying to the fact that the Cabinet had advised Johnson that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and that secretaries Seward and Stanton had agreed to prepare a draft of a veto message. Benjamin Curtis argued that the testimony was relevant because an article of impeachment charged the President with "intending" to violate the Constitution, and that Welles's testimony tended to show that the President honestly believed the law to be unconstitutional. Over the House Managers' objection, Chief Justice Chase ruled the evidence admissible, but was overruled by the Senate 29 to 20, and the testimony was not allowed.

Chief Justice Chase

Final arguments in the impeachment trial stretched from April 22 to May 6, with the Managers speaking for six days and counsel for the President speaking for five days. Arguments ranged from the technical to the hyperbolic. Manager Thaddeus Stevens railed against the "wretched man, standing at bay, surrounded by a cordon of living men, each with the axe of an executioner uplifted for his just punishment." Manager John Bingham brought the crowded galleries to its feet with his thunderous closing:

"May God forbid that the future historian shall record of this day's proceedings, that by reason of the failure of the legislative power of the people to triumph over the usurpations of an apostate President, the fabric of American empire fell and perished from the earth!...I ask you to consider that we stand this day pleading for the violated majesty of the law, by the graves of half a million of martyred hero-patriots who made death beautiful by the sacrifice of themselves for their country, the Constitution and the laws, and who, by their sublime example, have taught us all to obey the law; that none are above the law;... and that position, however high, patronage, however powerful, cannot be permitted to shelter crime to the peril of the republic."

William Groesbeck's peroration for the President offered a spirited defense of Johnson's view of reconstruction:

"He was eager for pacification. He thought that the war was ended. It seemed so. The drums were all silent; the arsenals were all shut; the roar of the cannon had died away to the last reverberations; the army was disbanded; not a single enemy confronted us in the field. Ah, he was too eager, too forgiving, too kind. The hand of reconciliation was stretched out to him and he took it. It may be that he should have put it away, but was it a crime to take it? Kindness, forgiveness a crime? Kindness a crime? Kindness is statesmanship. Kindness is the high statesmanship of heaven itself. The thunders of Sinai do but terrify and distract; alone they accomplish little; it is the kindness of Calvary that subdues and pacifies."

William Everts contended in his closing argument for the President that violation of the Tenure of Office Act did not rise to the level of an impeachable offense:

"They wish to know whether the President has betrayed our liberties or our possessions to a foreign state. They wish to know whether he has delivered up a fortress or surrendered a fleet. They wish to know whether he has made merchandise of the public trust and turned the authority to private gain. And when informed that none of these things are charges, imputed, or even declaimed about, they yet seek further information and are told that he has removed a member of his cabinet."

Impeachment trial of Andew Johnson

Finally, Attorney General Henry Stanbery's closing for the President compared conviction to a despicable crime:

"But if, Senators, as I cannot believe, but as has been boldly said with almost official sanction, your votes have been canvassed and the doom of the President is sealed, then let that judgment not be pronounced in this Senate Chamber; not here, where our Camillus in the hour of our greatest peril, single-handed, met and baffled the enemies of the Republic; not here, where he stood faithful among the faithless; not here, where he fought the good fight for the Union and the Constitution; not in this Chamber, whose walls echo with that clarion voice that, in the days of our greatest danger, carried hope and comfort to many a desponding heart, strong as an army with banners. No, not here. Seek out rather the darkest and gloomiest chamber in the subterranean recesses of this Capitol, where the cheerful light of day never enters. There erect the altar and immolate the victim."

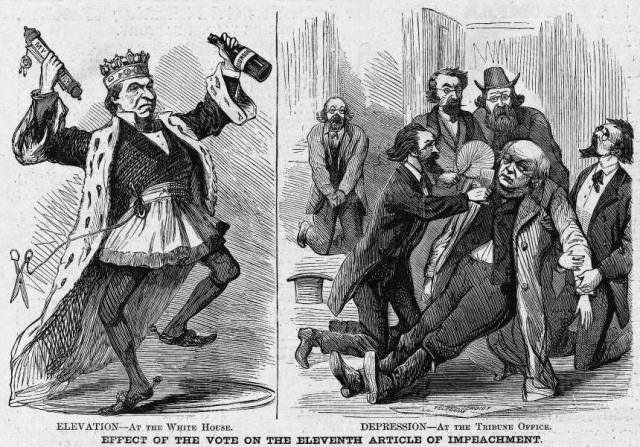

Outwardly, House Managers were confident. Benjamin Butler told a Republican audience on May 4 that "The removal of the great obstruction is certain. Wade and prosperity are sure to come with the apple blossoms." Privately, the were less optimistic. In the week before the vote, much money was being bet by professional gamblers on the outcome of the trial, and the odds favored acquittal. On May 11, from 11 am to midnight, senators debated the merits of the case behind closed doors. The best chance for conviction seemed to rest with the eleventh article that charged the President with attempting to prevent Stanton from resuming his office after the Senate disapproved his suspension. It was obvious that the vote would be very close, depending upon the decisions of two or three undecided Senators. No Senator's vote was more critical than that of Edmund Ross of Kansas, who remained stubbornly silent throughout the trial and discussions.

At noon on May 16, 1868, the High Court of Impeachment was called to order by Chief Justice Chase. The galleries were packed and the House of Representatives was present en mass. A motion was made and adopted to vote first on the eleventh article. The Chief Justice said, "Call the roll." Historian David Dewitt described the tension as the roll call reaches the name of Senator Ross:

"Twenty-four 'Guilties' have been pronounced and ten more certain are to come. Willey is almost sure and that will make thirty-five. Thirty-six votes are needed, and with this one vote the grand consummation is attained, Johnson is out and Wade in his place. It is a singular fact that not one of the actors in that high scene was sure in his own mind how his one senator was going to vote, except, perhaps, himself. 'Mr. Senator Ross, how say you?' the voice of the Chief Justice rings out over the solemn silence. 'Is the respondent, Andrew Johnson, guilty or not guilty of a high misdemeanor as charged in this article?' The Chief Justice bends forward, intense anxiety furrowing his brow. The seated associates of the senator on his feet fix upon him their united gaze. The representatives of the people of the United States watch every movement of his features. The whole audience listens for the coming answer as it would have listened for the crack of doom. And the answer comes, full, distinct, definite, unhesitating and unmistakable. The words 'Not Guilty' sweep over the assembly, and, as one man, the hearers fling themselves back into their seats; the strain snaps; the contest ends; impeachment is blown into the air."

Although John F. Kennedy described Edmund Ross as a "profile in courage" in his book of the same name, historian David O. Stewart believes otherwise. In his excellent book Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy, Stewart contends that Ross's vote was bought. Defenders of the President had raised $150,000 for an "Acquittal Fund," and Stewart believes that Johnson's supporters were approaching Republican senators and offering bribes. Political fixer Perry Fuller, a key contributer to Ross's Senate campaign, spent the night before the Senate vote with Ross, who until that time had indicated an intent to vote for conviction. Stewart contends that a few days after the vote, Fuller was rewarded for his successful efforts to thwart conviction with an appointment by Johnson to the position of head of the Internal Revenue Service, perhaps the best post in Washington for someone interested in feathering his own nest. When Congress refused to confirm Fuller, Johnson appointed him as collector of taxes for the Port of New Orleans, a position which Fuller made personally enriching for the remainder of the Johnson term.

The debate continues as to whether Johnson should have been convicted. David Stewart argues, and I agree, that Johnson deserved to be removed from office, but not for the arguable offense of violating the Tenure of Office Act or for being a blowhard. Instead, Johnson should have been convicted because he seriously undermined efforts to improve the lot of the country's newly freed slaves and because he stood idly by, and provided not a finger of federal assistance, even when ex-slaves were being slaughtered on southern highways. Johnson was a confrontational and insensitive president at a time when the nation desperately needed someone to heal the nation's wounds--someone like Abraham Lincoln.

Still, the impeachment trial had its value. It served to channel the potentially explosive anger in many parts of the country against Andrew Johnson into a morality play. Things could have been worse.