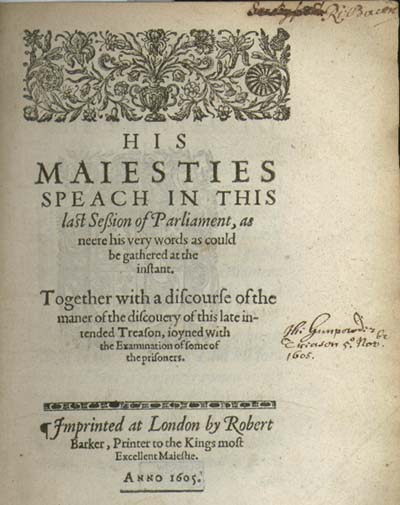

Speech of King James I to both Houses of Parliament, upon occasion of the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot (November 9, 1605)

MY Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and you the Knights and Burgesses of this Parliament; It was far from my thoughts, till very lately, before my coming to this place, that this Subject should have been ministred unto me, whereupon I am now to speak. But now it so falleth out, That whereas in the preceding Session of this Parliament, the principal occasion of my Speech was, to thank and congratulate all you of this House, and in you, all the whole Common-wealth (as being the representative Body of the State) for your so willing, and loving receiving, and embracing of me in that place, which God and Nature by descent of Bloud, had in his own time provided for me: So now my subject is, to speak of a far greater Thanksgiving than before I gave to you, being to a far greater person, which is to GOD, for the great and miraculous Delivery he hath at this time granted to me, and to you all, and consequently to the whole Body of this Estate,

I must therefore begin with this old and most approved Sentence of Divinity, Misericordia Dei supra omnia opera ejus. For Almighty GOD did not furnish so great matter to his Glory, by the Creation of this great World, as he did by the Redemption of the same. Neither did his Generation of the little World, in our old and first ADAM, so much set forth the praises of GOD in his Justice and Mercy, as did our Regeneration in the last and second ADAM.

And now I must crave a little pardon of you, That since Kings are in the word of GOD itself called Gods, as being his Lieutenants and Vicegerents on earth, and so adorned and furnished with some sparkles of the Divinity; to compare some of the Works of GOD the Great King, towards the whole and general World, to some of his Works towards Me, and this little world of my Dominions, compassed and severed by the Sea from the rest of the Earth. For as GOD for the just punishment of the first great Sinner in the original world, when the Sons of GOD went in to the Daughters of Men, and the cup of their iniquities of all sorts was filled, and heaped up to the full, did by a general deluge and overflowing of waters, baptize the World to a general destruction, and not to general purgation (only excepted Noah and his family, who did repent and believe the threatenings of God's judgment:) So now, when the World shall wax old as a Garment, and that all the impieties and sins that can be devised against both the first and second Table, have, and shall be committed to the full measure; GOD is to punish the World the second time by Fire, to the general destruction and not purgation thereof. Although as it was done in the former to Noah and his Family by the waters; So shall all we that believe be likewise purged, and not destroyed by the Fire. In the like sort, I say, I may justly compare these two great and fearful Doomsdays, wherewith GOD threatened to destroy me, and all you of this little World that have interest in me. For although I confess, as all mankind, so chiefly Kings, , as being in the higher places like the high Trees, or stayest Mountains, and steepest Rocks, are most subject to the daily tempests of innumerable dangers; and I amongst all other Kings, have ever been subject unto them, not only ever since my birth, but even as I may justly say, before my birth, and while I was yet in my Mothers belly: yet have I been exposed to two more special and greater dangers than all the rest.

The first of them, in the Kingdom where I was born, and passed the first part of my life: And the last of them here, which is the greatest. In the former, I should have been baptized in blood, and in my destruction, not only the Kingdom, wherein I then was, but ye also by your future interest, should have tasted of my ruin. Yet it pleased GOD to deliver me, as it were, from the very brink of death, from the point of the dagger, and so to purge me by my thankful acknowledgement of so great a benefit. But in this which did so lately fall out, and which was a destruction prepared not for me alone, but for you all that are here present, and wherein no rank, age, or sex should have been spared; This was not a crying sin of bloud as the former, but it may well be called a roaring, nay, a thundering sin of Fire and Brim∣stone, from the which, God hath so miraculously delivered us all. What I can speak of this, I know not: Nay rather, what can I not speak of it? And therefore I must for horror say with the Poet. Vox Fauci bus haeret.

In this great and horrible attempt, whereof the like was never either heard or read, I observe three wonderful, or rather miraculous events.

First, in the cruelty of the Plot it self, wherein cannot be enough admired the horrible and fearful cruelty of their Device, which was not only for the destruction of my Person, nor of my Wife and Posterity only, but of the whole Body of the State in general; wherein should neither have been spared, or distinction made of young nor of old, of great nor of small, of man nor of woman: The whole Nobility, the whole Reverend Clergy, Bishops, and most part of the good Preachers, the most part of the Knights and Gentry; yea, and if that any in this Society were favourers of their Profession, they should all have gone one way: The whole Judges of the Land, with the most of the Lawyers and the whole Clerks: And as the wretch himself that is in the Tower, doth confess, it was purposely devised by them, and concluded to be done in this house; That where the cruel Laws (as they say) were made against their Religion, both place and persons should all be destroyed and blown up at once. And then consider therewithal the cruel form of that practice: for by three different sorts in general may mankind be put to death.

The First, by other men, and reasonable creatures, which is least cruel: for then both defence of men against men may be expected, and likewise who knoweth what pity GOD may stir up in the hearts of the Actors at the very instant? besides the many ways and means, whereby men may escape in such a present fury.

And the Second way more cruel than that, is by Animal and unreasonable creatures: for as they have less pity then men, so is it a greater horror, and more unnatural for men to deal with them: But yet with them both resistance may avail, and also some pity may be had, as was in the Lyons, in whose Den Daniel was thrown; or that thankful Lyon, that had the Roman slave in his mercy.

But the Third, which is most cruel and unmerciful of all, is the destruction by insensible and inanimate things; and amongst them all, the most cruel are the two Elements of Walter and Fire; and of those two the Fire most raging and merciless.

Secondly, How wonderful it is when you shall think upon the small, or rather no ground, whereupon the Practisers were enticed to invent this Tragedy. For if these Conspirators had only been bankrupt persons, or discontented upon occasion of any disgraces done unto them; this might have seemed to have been but a work of revenge. But for my own part, as I scarcely ever knew any of them, So cannot they alledge so much as a pretended cause of grief: And the wretch himself in hands doth confess, That there was no cause moving him or them, but merely, and only Religion. And specially, that Christian men, at least so called, Englishmen, born within the Countrey, and one of the specials of them, my sworn Servant, in an Honorable place, should Practise the destruction of their King, his Posterity, their Countrey and all: wherein their following obstinacy is so joyned to their former malice, as the fellow himself that is in hand, cannot be moved to discover any signes or notes of repentance, except only, that he doth not yet stand to avow, that he repents for not being able to perform his intent.

Thirdly, The discovery hereof is not a little * 1.8 wonderful, which would be thought the more miraculous by you all, if you were as well acquainted with my natural disposition, as those are who be near about me. For as I ever did hold suspition to be the sickness of a Tyrant, so was I so far upon the other extremity, as I rather contemned all advertisements, or apprehensions of practises. And yet now at this time was I so far contrary to my self, as when the Letter was shewed to me by my Secretary, wherein a general obscure advertisement was given of some dangerous blow at this time, I did upon the instant inter∣pret and apprehend some dark phrases therein, contrary to the ordinary Grammer construction of them, (and in another sort then I am sure any Divine, or Lawyer in any University would have taken them) to be meant by this horrible form of blowing us up all by Powder; and thereupon ordered, that search to be made, whereby the matter was discovered, and the man apprehended: whereas if I had apprehended or interpreted it to any other sort of danger, no worldly provision or prevention could have made us escape our utter destruction

And in that also, was there a wonderful providence of God, that when the party himself was taken, he was but new come out of his house from working, having his Firework for kindling ready in his pocket, wherewith as he confesseth, if he had been taken but immediately before, when he was in the House, he was resolved to have blown up himself with his Takers.

One thing for my own part have I cause to thank GOD in, That if GOD for our sins had suffered their wicked intents to have prevailed, it should never have been spoken nor written in ages succeeding, that I had died ingloriously in an Ale-house, a Stews, or such vile place, but mine end should have been with the most Honourable and best company, and in that most Honourable and fittest place for a King to be in, for doing the turns most proper to his Office; And the more have We all cause to thank and magnifie GOD for this his merciful Delivery. And specially I for my part, that he hath given me yet once leave, whatsoever should come of me hereafter, to assemble you in this Honourable place; And here in this place, where our general destruction should have been, to magnifie and praise him for Our general delivery; That I may justly now say of mine enemies and yours, as David doth often say in the Psalm, Inciderunt in foveam, quam fecerunt. And since Scipio an Ethnick, led only by the light of Nature, That day when he was accused by the Tribunes of the people of Rome, for misspending and wasting in his Punick wars the Cities Treasure, even upon the sudden brake out with that diversion of them from that matter, calling them to remembrance how that day, was the day of the year, wherein GOD hath given them so great a victory against Hannibal, and therefore it was fitter for them all, leaving other matters, to run to the Temple to praise GOD for that so great delivery, which the people did all follow with one applause: How much more cause have we that are Christians to bestow this time in this place for Thanksgiving to GOD for his great Mercy, tho we had had no other errand of assembling here at this time; wherein if I have spoken more like a Divine, than would seem to belong to this place, the matter it self must plead for mine excuse: for be∣ing here come to thank God for a Divine work of his Mercy, how can I speak of this deliverance of us from so hellish a practise, so well, as in language of Divinity, which is the direct opposite to so damnable an intention? And therefore may I justly end this purpose, as I did begin it with this Sentence, The mercy of God is above all his works.

It resteth now, that I should shortly inform you what is to be done hereafter upon the occasion of this horrible and strange accident. As for your part that are my faithful and loving Subjects of all degrees, I know that your hearts are so burnt up with zeal in this errand, and your tongues so ready to utter your dutiful affections, and your hands and feet so bent to concurr in the execution thereof, (for which as I need not to spurr you, so can I not but praise you for the same:) As it may very well be possible, that the zeal of your hearts shall make some of you in your speeches, rashly to blame such as may be innocent of this attempt;

But upon the other part I wish you to consider, That I would be sorry that any be∣ing innocent of this practise, either domestic or forrain, should receive blame or harm, for the same. For although it cannot be denied, That it was the only blind superstition of their errors in Religion, that led them to this desperate device; yet doth it not follow, That all professing that Romish Religion were guilty of the same. For as it is true, That no other sect of Heretiques, not excepting Turk Iew, nor Pagan, no not even those of Calicute who adore the Devil, did ever maintain by the grounds of their Religion, That it was lawful, or rather meritorious (as the Romish Catholicks call it) to murther Princes or people for quarrel of Religion. And although particular men of all professions of Religion have been some Thieves, some Murtherers, some Traitors, yet ever when they came to their end and just punishment, they confessed their fault to be in their nature, and not in their profession, (These Romish Catholicks only excepted:) Yet it is true on the other side, That many honest men blinded peradventure with some opinions of Popery, as if they be not found in the questions of the Real presence, or in the number of the Sacraments, or some such School-question: yet do they either not know, or at least, not believe all the true grounds of Popery, which is indeed, The mistery of iniquity. And therefore do we justly confess, that many Papists, especially our fore-fathers, laying their only trust upon Christ and his Merits at their last breath, may be, and oftentimes are saved; detesting in that point, and thinking the cruelty of Puritans worthy of Fire, that will admit no salvation to any Papist. I therefore thus do conclude this point, That as upon the one part many honest men, seduced with some errors of Popery, may yet remain good and faithful Subjects: So upon the other part, none of those that truly know and believe the whole grounds, and School-conclusions of their Doctrine, can ever prove either good Christians, or faithful Subjects. And for the part of forrain Princes and States, I may so much the more acquite them, and their Ministers, of their knowledge and consent to any such villany, as I may justly say, that in that point I better know all Christian Kings by my self, that no King nor Prince of Honor will ever abase himself so much, as to think a good thought of so base and dishonourable a Treachery: wishing you therefore, that as GOD hath given me an happy peace and amity, with all other Christian Princes my neighbors (as was even now very gravely told you by my L. Chancellor) that so you will reverently judge and speak of them in this case. And for my part I would wish with those antient Philosophers, that there were a Christal window in my breast, wherein all my people might see the secretest thoughts of my heart, for then might you all see no alteration in my mind for this accident, further than in those two points. The first, caution and wariness in government: to discover and search out the mysteries of this wickedness as far as may be: The other, after due trial, Severity of punishment upon those that shall be found guilty of so detestable and unheard of villany. And now in this matter, if I have troubled your ears with an abrupt Speech, undisgested in any good method or order; you have to consider that an abrupt, and unadvised Speech doth best become in the relation of so abrupt and unorderly an accident.

And although I have ordained the Proroguing of this Parliament until after Christmass upon two necessary respects: whereof the first is, that neither I nor my Council can have leasure at this time both to take order for the apprehension and trial of these Conspirators, and also to wait upon the daily affairs of the Parliament, as the Council must do. And the other reason is, the necessity at this time of divers of your presences in your Shires that have Charges and Commandments there. For as these wretches thought to have blown up in a manner the whole world of this Island, every man being now come up here, either for publick causes of Parliament, or else for their own private causes in Law, or otherwise: So these Rebels that now wander through the Countrey, could never have gotten so fit a time of safety in their passage, or whatsoever unlawful Actions, as now when the Countrey by the foresaid occasions is in a manner left desolate, and waste unto them. Besides that, It may be that I shall desire you at your next Session, to take upon you the Judgment of this Crime: for as so extraordinary a Fact deserves extraordinary Judgment, So can there not I think (following even their own Rule) be a fitter Judgment for them, then that they should be measured with the same measure wherewith they thought to measure us: and that the same place and persons, whom they thought to destroy, should be the just avengers of their so unnatural a Parricide: Yet not knowing that I will have occasion to meet with you my self in this place at the beginning of the next Session of this Parliament (because if it had not been for delivering of the Articles agreed upon by the Commissioners of the Union, which was thought most convenient to be done in my presence, where both Head and Members of the Parliament were met together, my presence had not otherwise been requisite here at this time:) I have therefore thought good for conclusion of this Meeting, to discourse to you somewhat anent the true nature and definition of a Parliament, which I will remit to your memories, till your next sitting down; that you may then make use of it as occasion shall be ministred.

For albeit it be true, that at the first Session of my first Parliament, which was not long after mine Entry into this Kingdome, It could not become me to informe you of any thing belonging to Law or State here: (for all knowledge must either be infured, or acquired, and seeing the former sort thereof is now with Prophesie, ceased in the World, it could not be possible for me, at my first Entry here, before Experience had taught it me, to be able to understand the particular Mysteries of this State:) yet now that I have reigned almost three years amongst you, and have been careful to observe those things that belong to the Office of a King, albeit that Time be but a short time for experience in others, yet in a King may it be thought a reasonable long time, especially in me, who, although I be but in a manner a new King here, yet have been long acquainted with the office of a King in such another Kingdom, as doth nearest of all others agree with the Lawes and Customes of this State. Remitting to your consideration to judge of that which hath been concluded by the Commissioners of the Union, wherein I am at this time to signifie unto you, That as I can bear witness to the foresaid Commissioners, that they have not agreed nor concluded therein any thing, wherein they have not foreseen as well the Weale and Commodity of the one Countrey, as of the other; So can they all bear me record, that I was so far from pressing them to agree to any thing, which might bring with it any prejudice to this People; as by the contrary I did ever admonish them, never to conclude upon any such Union, as might carry hurt or grudge with it to either of the said Nations: for the leaving of any such thing, could not but be the greatest hinderance that might be to such an Action, which GOD by the Laws of Nature had provided to be in his own time, and hath now in effect perfected in my Person; to which purpose my Lord Chancellor hath better spoken, then I am able to relate.

And as to the nature of this high Court of Parliament, It is nothing else but the Kings great Council, which the King doth assemble, either upon occasion of interpreting, or abrogating old Lawes, or making of new, according as ill manners shall deserve, or for the publick punishment of notorious evil doers, or the praise and reward of the vertuous and well deservers; wherein these four things are to be considered.

First, Whereof this Court is composed.

Secondly, What Matters are proper for it.

Thirdly, To what end it is ordained.

And Fourthly, What are the meanes and wayes whereby this end should be brought to pass.

As for the thing it self, It is composed of a Head and a Body: The Head is the King, the Body are the members of the Parliament. This Body again is subdivided into two parts; The Upper and Lower House: The Upper compounded partly of Nobility, Temporal men, who are heritable Councellors to

to the high Court of Parliament by the honor of their Creation and Lands: And partly of Bishops, Spiritual men, who are likewise by the vertue of their place and dignity Counsellors, Life-Renters, or Ad vitam of this Court. The other House is composed of Knights for the Shire; and Gentry, and Burgesses for the Towns. But because the number would be infinite for all the Gentlemen and Burgesses to be present at every Parliament, Therefore a certain number is selected and chosen out of that great Body, serving onely for that Parliament, where their persons are the representation of that Body.

Now the Matters whereof they are to treat ought therefore to be general, and rather of such matters as cannot well be performed without the assembling of that general Body, and no more of these generals neither, then necessity shall require: for as in Corruptissima Republica sunt plurimae leges: So doth the life and strength of the Law consist not in heaping up infinite and confused numbers of Lawes, but in the right interpretation and good execution of good and wholsome Laws. If this be so then, neither is this a place on the one side for every rash and harebrain fellow to propone new Laws of his own invention: nay rather I could wish these busie heads to remember that Law of the Lacedemonians, That whosoever came to propone a new Law to the People, behoved publickly to present himself with a Rope about his neck, that in case the Law were not allowed, he should be

hanged therewith. So wary should men be of proponing Novelties, but most of all, not to propone any bitter or seditious Laws, which can produce nothing but grudges and discontentment between the Prince and his people: nor yet is it on the other side a convenient place for private men under the colour of general Laws, to propone nothing but their own particular gain, either to the hurt of their private neighbours, or to the hurt of the whole State in general, which many times under fair and pleasing Titles, are smoothly passed over, and so by stealth procure without consideration, that the private meaning of them tendeth to nothing but either to the wreck of a particular party, or else under colour of publique benefit to pill the poor people, and serve as it were for a general Impost upon them for filling the purses of some private persons.

And as to the end for which the Parliament is ordained, being only for the advancement of Gods glory, and the establishment and wealth of the King and his people: It is no place then for particular men to utter there their private conceipts, nor for satisfaction of their curiosities, and least of all to make shew of their eloquence, by tyning the time with long studyed and eloquent Orations. No, the reverence of GOD, their King, and their Countrey being well setled in their hearts, will make them ashamed of such toyes, and remember that they are there as sworn Councellors to their King, to give their best advice for the furtherance of his Service, and the flourishing Weale of his Estate.

And lastly, if you will rightly consider the means and wayes how to bring all your labors to a good end, you must remember, That you are here assembled by your lawful King to give him your best advices, in the matters proposed by bim unto you, being of that nature, which I have already told, wherein you are gravely to deliberate, and upon your consciences plainly to determine how far those things propounded do agree with the Weale, both of your King, and of your Country, whose weales cannot be separated. And as for my self, the world shall ever bear me witness, That I never shall propone any thing unto you, which shall not as well tend to the Weale publick, as to any benefit for me: So shall I never oppose my self to that, which may tend to the good of the Commonwealth, for the which I am ordained, as I have often said. And as you are to give your advice in such things, as shall by your King be proposed: So is it on your part your duties to propone any thing that you can, after mature deliberation judge to be needful, either for these ends already spoken of, or otherwise for the discovery of any latent evil in the Kingdom, which peradventure may not have come to the Kings eare. If this then ought to be your grave manner of proceeding in this place, Men should be ashamed to make snew of the quickness of their wits here, either in taunting, scoffing, or detracting the Prince or State in any point, or yet in breaking jests upon their fellowes, for which the Ordinaries or Alehouses are fitter places, than this Honourable and high Court of Parliament.

In conclusion then, since you are to break up, for the Reasons I have already told you, I wish such of you as have any charges in your Countreys, to hasten you home for the repressing of the insolencies of these Rebels, and apprehension of their persons, wherein, as I heartily pray to the Almighty for your prosperous success: So do I not doubt, but we shall shortly hear the good newes of the same; And that you shall have an happy re∣turn, and meeting here to all our comforts.

Here the Lord Chancellor spake touching the Proroguing of the Parliament. And having done, his Majesty rose again, and said:

Since it pleased GOD to grant me two such notable Deliveries upon one day of the week, which was Tuesday, and likewise one day of the Moneth, which was the fifth; thereby to teach me, That as it was the same Devil that still persecuted me: So it was one and the same GOD that still mightily delivered me; I thought it therefore not amiss, that the one and twentieth day of January, which fell to be upon Tuesday, should be the day of meeting of this next Session of Parliament, hoping and assuring my Self, that the same GOD who hath now granted me and you all so notable and gracious a Delivery,

shall prosper all our affairs at that next Session, and bring them to a happy conclusion. And now I consider God hath well provided it that the ending of this Parliament hath been so long continued; For as for mine own part, I never had any other intention, but only to seek so far my weale, and prosperity, as might conjunctly stand with the flourishing State of the whole Common-wealth, as I have often told you: So on the other part I confess, if I had been in your places at the beginning of this Parliament (which was so soon after mine entry into this Kingdom, wherein ye could not possibly have so perfect a knowledge of mine inclination, as experience since hath taught you) I could not but have suspected, and mis-interpreted divers things, In the trying whereof, now I hope, by your experience of my behaviour and form of government, you are well enough cleared, and resolved.

(London: Printed by Tho. Newcomb, and H. Hills. 1679.)