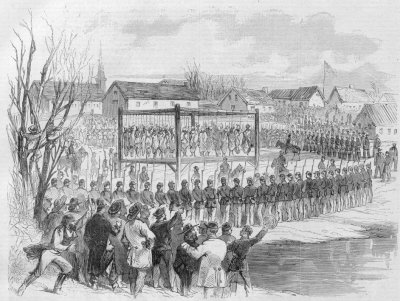

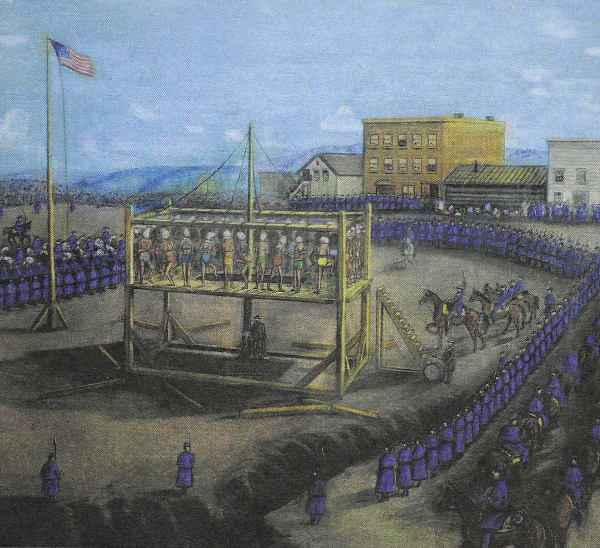

A framed sketch of the scene depicted on this site's homepage, the execution of thirty-eight Sioux on December 26, 1862, used to fascinate me when, as a boy in Mankato, Minnesota, I would visit the Blue Earth County Historical Museum. Apart from its macabre appeal, the picture impressed me because it captured the most famous event in the history of my hometown (easily surpassing in significance the death there of an obscure Vice President who died while changing trains on his way to the Black Hills). The hanging, following trials which condemned over three hundred participants in the 1862 Dakota Conflict, stands as the largest mass execution in American history. Only the unpopular intervention of President Lincoln saved 265 other Dakota and mixed-bloods from the fate met by the less fortunate thirty-eight. The mass hanging was the concluding scene in the opening chapter of a story of the American-Sioux conflict that would not end until the Seventh Cavalry completed its massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890.

In 1862 the Sioux Nation, about 25,000 strong, stretched from the Big Woods of Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains. There were seven Sioux tribes, including three western tribes, collectively called the Lakota, and four eastern tribes living in Minnesota and the eastern Dakotas called the Dakota. About 7,000 members of the four Dakota tribes lived on a reservation bordering what was in 1862 the frontier, the Minnesota River in southwestern Minnesota. The Dakota Conflict (or Dakota War or Sioux Uprising) involved primarily the two southernmost Dakota tribes, the Mdewakantons and Wahpekutes. Tribes consisted of bands, each with a leader or chief. The Mdewakantons, for example, were divided into nine bands. A majority of the 4,000 members of the two northern tribes, the Sissetons and the Wahpetons, were opposed to the fighting. A large number of Sissetons and Wahpetons had been converted both to farming and Christianity, and had both moral objections and strong reasons of self-interest for keeping peace with the whites. In addition to pure-blood Indians, there were many so-called mixed-bloods, the products of relationships between Indians and settlers. A majority of mixed-bloods sided with whites or avoided participation in the Conflict altogether.

A decade before the Dakota Conflict, the Minnesota Territory, stretching from the upper Mississippi to the Missouri River, was still mostly Indian country. The conifer forest and lakes of Northern Minnesota belonged to the Ojibway (or Chippewa), while the deciduous forests and prairie of southern Minnesota was shared by the Dakota and a much smaller number of Winnebago. In 1851, however, the Dakota by treaty agreed to give up most of southern Minnesota and a small part of South Dakota. The land was ceded to the United States in return for two twenty-mile wide by seventy-mile long reservations along the Minnesota River and annuity payments totaling $1.4 million dollars over a fifty-year period. Seven years later, in exchange for increased annuity payments, the Dakota ceded about half of their reservation land. [LINK TO MAP SHOWING RESERVATION LAND]

The Conflict

The causes of the the Dakota Conflict are many and complex. The treaties of 1851 and 1858 contributed to tensions by undermining the Dakota culture and the power of chieftains, concentrating malcontents, and leading to a corrupt system of Indian agents and traders. Settlers, with their agricultural practices, degraded habitats in traditional hunting grounds. Annuity payments reduced the once proud Dakota to the status of dependents. They reduced the power of chiefs because annuity payments were made directly to individuals rather than through tribal structures. They created bitterness because licensed traders sold goods to Indians at 100% to 400% profit and frequently took "claims" for money from individual Dakota paid out of tribal funds. No effective means of legal recourse was available to wronged Dakota, leading some Dakota to talk of another option open to them: robbery and violence. Rumors abounded that "the Great Father," facing the huge costs of the Civil War, was flat broke. The fact that the Dakota people were squeezed into a small fraction of their former lands made it easy, according to Minnesota historian William Folwell, "for malcontents to assemble frequently to growl and fret together over grievances." [LINK TO BISHOP WHIPPLE'S DISCUSSION OF CAUSES OF WAR]

Annuity payments for the Dakota were late in the summer of 1862. An August 4, 1862 confrontation between soldiers and braves at the Upper Agency at Yellow Medicine led to a decision to distribute provisions on credit to avoid violence. At the Lower Agency at Redwood, however, things were handled differently. At an August 15, 1862 meeting attended by Dakota representatives, Indian Agent Thomas Galbraith, and representatives of the traders, the traders resisted pleas to distribute provisions held in agency warehouses to starving Dakota until the annuity payments finally arrived. Trader Andrew Myrick summarized his position in the bluntest possible manner: "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass." Unbeknownst to those gathered at the Lower Agency, the long-delayed 1862 annuity payments were already on their way to the Minnesota frontier. On August 16, a keg with $71,000 worth of gold coins reached St. Paul. The next day the keg was sent to Fort Ridgely for distribution to the Dakota. It arrived a few hours too late to prevent an unprecedented outbreak of violence.

On Sunday, August 17, four Dakota from a breakaway band of young malcontents were on a hunting trip, about forty miles north of Fort Ridgely, when they came across some eggs in a hen's nest along the fence line of a settler's homestead. When one of the four took the eggs, another of the group warned him that the eggs belonged to a white man. The first young man became angry, dashed the eggs to the ground, and accused the other of being afraid of white men, even though half-starved. Apparently to disprove the accusation of cowardice, the other Dakota said that to show he was not afraid of white men he would go the house and shoot the owner. He challenged the others to join him. Minutes later three white men, a white woman, and a fifteen-year-old white girl lay dead.[LINK TO CARTOON STORY OF FIRST VIOLENCE]

Big Eagle, a Dakota Chief, recounted what happened after the young men returned to Chief Shakopee's camp near the Lower Sioux Agency late on the night of August 17:

The tale told by the young men created the greatest excitement. Everybody was waked up and heard it. Shakopee took the young men to Little Crow's house (two miles above the agency), and he sat up in bed and listened to their story. He said war was now declared. Blood had been shed, the payment would be stopped, and the whites would take a dreadful vengeance because women had been killed. Wabasha, Wacouta, myself and others still talked for peace, but nobody would listen to us, and soon the cry was "Kill the whites and kill all these cut-hairs who will not join us." A council was held and war was declared. Parties formed and dashed away in the darkness to kill settlers. The women began to run bullets and the men to clean their guns....

At this time my village was up on Crow creek, near Little Crow's. I did not have a very large band -- not more than thirty or forty fighting men. Most of them were not for the war at first, but nearly all got into it at last. A great many members of the other bands were like my men; they took no part in the first movements, but afterward did. The next morning, when the force started down to attack the agency, I went along.... The killing was nearly all done when I got there. Little Crow was on the ground directing operations. I saw all the dead bodies at the agency. Mr. Andrew Myrick, a trader, with an Indian wife, had refused some hungry Indians credit a short time before when they asked him for provisions. He said to them; "Go and eat grass." Now he was lying on the ground dead, with his mouth stuffed full of grass, and the Indians were saying tauntingly: "Myrick is eating grass himself." When I returned to my village that day I found that many of my band had changed their minds about the war, and wanted to go into it. All the other villagers were the same way.[Big Eagle's Account, Through Dakota Eyes]

Big Eagle

Events moved quickly. In the first bloody phase of the war, under the loose direction of Little Crow, the Dakota massacred farm families. To understand the intense desire of Minnesotans for swift and terrible justice in the trials that followed the Conflict, one need only look at what happened in one settlement near the reservation on August 18. Fifteen to twenty Dakota, carrying knifes and hatchets, descended on the farmhouses of Milford, Minnesota. At each house, they gained entry to the house by going to the front door and asking for water. Once inside, the killing began. At one family homestead, they killed an entire family of six, including four children aged two to eight. The warriors disrobed the bodies of two of the girls; they decapitated one of them. The Milford attacks resulted in the deaths of 53 settlers, including twenty children. Not a single Dakota warrior died in the attacks.

Similar indiscriminate killing of whites occurred elsewhere during the first two days of the war. The Dakota wiped the village of Leavenworth off the map, killing everyone of its 23 residents. At eight different sites, Dakota killed 13 or more civilians. The majority of victims were women and children. In all, an estimated 250 whites died in the first three days of fighting. Killing whites, the Dakota decided, was as easy as killing sheep.

"Massacre" is a loaded word. Yet, by any measure, these killings by Dakota warriors were just that--massacres. Yet what these Dakota did do the white settlers of Minnesota was no different than what they had done in earlier conflicts with their hated enemies, the Ojibwes, who occupied the forested lands just to their north and east. When the Dakota went to war, they considered everyone on the other side fair game.

Not all war parties, however, killed indiscriminately. Some Dakota chose to take women and children captive, rather than killing them. Who lived and who died depended on the whims of individual warriors.

Dakota warriors launched attacks Fort Ridgely and the town of New Ulm. Forty-six officers and enlisted men from the Fort Ridgely, who had set out to suppress the outbreak, were ambushed along a river. Just thirteen men returned to the fort alive. Panicking settlers fled eastward from 23 counties, leaving the southwestern Minnesota frontier largely depopulated except for the barricaded fortifications at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm. On August 23, a second Dakota attack on New Ulm left most of the town burned to the ground, and 1,200 refugees, mostly women, children, and wounded men, set off in wagons and on foot for Mankato, thirty miles away.

On August 26, three days after Governor Alexander Ramsey appointed Colonel Henry Sibley, a former governor, to command American forces that would attempt to suppress the uprising, Sibley advanced from the east with 1,400 soldiers toward Fort Ridgely. As squads of mounted and armed men streamed towards the scence of the conflict, more tragedies ensued. Dakota warriors attacked a group of volunteers gathering up the bodies of murdered settlers along roadsides and in homes. Twenty men from the burial party, and ninety of their horses, died in the atack.

But, within days, Sibley and his men succeeded in lifting the Dakota siege at Fort Ridgely, and the second phase of the Dakota Conflict-- an organized American military effort to defeat and punish the Sioux-- began.

President Lincoln federalized the state militia and put the troops under the command of General John Pope. Pope, fresh from his crusing defeat at the second battle of Bull Run, never got closer to the fighting than St. Paul's International Hotel. There he busied himself sending telegrams to Washington. He asked for additional troops and urged extermination of what the called "the wild beasts" and "maniacs" a hundred miles to the west.

Meanwhile, divisions among the Dakota increased. To the north, the chiefs of the Upper Agency region opposed the fighting. Chiefs Red Iron and Standing Buffalo even threatened to fire upon any of Little Crow's warriors who entered their territory. A key fact is this: most of the 7,000 Dakota in Minnesota opposed the war from the beginning and took no part in it.

But Little Crow's offensive continued to achieve success through early September. At dawn on September 2 at Birch Coulee Creek, Dakota warriors attacked a 170-man party of soldiers sent out to bury the bodies of settlers, killing 20 soldiers and 90 horses. Other Dakota attacks were made at Acton, Hutchinson, and Fort Abercrombie. Little Crow is generally acknowledged to have been the leader of the warring Dakota, but Chiefs Mankato, Big Eagle, Shakopee and others played significant leadership roles.

By mid-September, the initiative had shifted to the American forces. On September 23, in the decisive Battle of Wood Lake, 700 to 1,200 Dakota warriors were forced to withdraw after suffering heavy casualties. Meanwhile, divisions among Dakota on the war increased. During the Wood Lake Battle, "friendlies" (as Dakota opposed to the war were labeled) were able to seize control of white captives and bring them into their own camp. In late September, the friendlies released 269 white prisoners to the control of Colonel Sibley. Penned in to the north and south, facing severe food shortages and declining morale, many Dakota warriors chose to surrender. Together with those taken captive, the ranks of Dakota prisoners soon swelled to 1,250. The six-week war was over, having cost the lives of between 400 and 600 whites and hundreds (no more reliable estimate has been made) of Dakota. A decision had to be made. What should be done with the Dakota prisoners? [LINK TO CARTOON STORY ABOUT WOOD LAKE BATTLE AND SURRENDER]

The Trials and Mass Execution

The question became whatt to do with the Dakota prisoners. Most settlers and soldiers urged annihilation. Colonel Sibley, however, had another idea.

On September 28, 1862, Colonel Sibley appointed a five-member military commission to "try summarily" Dakota and mixed-bloods for "murder and other outrages" committed against Americans. Whether Sibley had authority to appoint such a commission is a matter of substantial dispute, but he seemed to act with the good intention of avoiding vigilante justice. The commission was convened immediately, meeting first in a military tent near Camp Release (close to modern-day Montevideo, Minnesota). [PHOTO OF LOG COURTHOUSE] The first order of business was to identify both witnesses and potential defendants. Reverend Stephen Riggs, who had worked for twenty-five years as a missionary to the Dakota and who had served as chaplain for Sibley's military expedition, proved to be an invaluable asset. He spoke the Dakota language and his Dakota parishioners trusted him. By enlisting their help, Riggs effectively served as a one-man grand jury.

To understand the final outcome of the trials that followed, it is important to distinguish between two types of violence. Some Dakota participated in massacres--and, in a couple of instances, rapes of white settlers. Other Dakota participated only in battles, such as the sieged of Fort Ridgely or the two assaults on St. Paul. (Although one could argue that the an assault on a town defended only by local residents is not a battle.) Generally, we do not think of warriors or soldiers who participate only in battlefield actions as murderers. On the other hand, the indiscriminate killing of civilians is generally treated differently, considered a war crime punishable under the law.

The trials moved to the summer kitchen cabin of trader Francois LaBathe, at the Lower Sioux Agency. Sixteen trials were conducted the first day at Camp Release, resulting in convictions and death sentences for ten prisoners and acquittals for another six. Over the six weeks that followed, the military court would try a total of 393 cases, convicting 323 and sentencing 303 to death by hanging. Reverend Riggs gathered much of the evidence and produced many of the witnesses.

The trials proceeded in three batches. The first to be tried was Joseph Godfrey (or Otakle), the son of a French-Canadian father and an African-American mother. Godfrey faced charges of "killing seven white women and children, more or less, peaceable citizens of the United States." Unlike most criminal trials, where the prosecution presents its case first, the court called Godfrey himselff as the first witness. Going first is worst. It locks in testimony and opens the defendant up to counter-charges from people that he implicates in his testimony.

Godfrey, in what the trial recorder described as "a voice of the most marvelous sweetness," testified that he was "mowing hay" when approached on horseback by a gun-toting Dakota warrior. Apparently, the warrior did not know what to make of the dark-skinned Godfrey. With his gun cocked, the warrior told Godfrey the Dakota were out to kill whites. In Godfrey's words, "He asked me which way I would go." Godfrey claimed that he decided to go with the Indians out of duress: "I have my wife and children I didn't want killed." Godfrey and the warrior joined up with a large group of Indians at a creek about a mile from Godfrey's house. There the warrriors insisted that Godfrey change from pants into breechcloth and put on war paint. Godfrey, in his testimony, admitted that he joined in various battles and massacres--and provided vivid details about all of them. For example, he told the court that at one settler's home, the war party found the table set for a family dinner. Spying the table, a warrior told Godfrey, "After we kill, we will have dinner." Godfrey named names. For example, he identified a Dakota who knifed an old man and then "cut him all to pieces." He named another who shot a woman and then kicked and killed her children.

The question for the military commission was whether Godfrey acted as a willing participant or whether he did what he did to save his own life. Godfrey admitted he drove wagons for Dakota warriors. He admitted seizing horses. He admitted being present at massacres. He even admitted to firing shots during the assault on New Ulm. But the one thing Godfrey did not admit to was murder. He claimed always to have been a reluctant warrior.

Six prosecution witnesses testified against Godfrey. They included a woman held captive by the Dakota who described Godfrey as "whooping around" and "happy with the Indians." She testified that a Dakota warrior told her that Godfrey led a raid into a house and clubbed an occupant with a hatchet. Another former captive testified, "He appeared to me to be with the Indians, and to act as they did." Most damningly, the father of a mixed-race friend of Godfrey's testified that Godfrey bragged about killing seven men. "He never told me he was forced into it," the witness said.

The military commission voted to sentence Godfrey to death. At the same time, however, they cited his "air of candor" and "valuable testimony and information" in their recommended commutation of his sentence to imprisonment for ten years. None of the other 300-plus defendants the commission sentenced to death received such a recommendation.

The trials that followed Godfrey's troubling case were quick affairs, getting quicker as they progressed. In the first batch of 29 trials, most prisoners received death sentences, but six received acquittals. The commission was not just a conviction mill; it insisted at least on some credible evidence of guilt before convicting. On the other hand, the bar for conviction was low. Consider that the last batch of 253 trials took place over ten days. That's a rate of more than 25 trials per day. Soldiers escorted the defendants into the courtroom in manacled pairs, eight at a time. The commission heard nearly 40 cases on November 3, the last day it met.

How could the trials move so quickly. Essentially, it is because the commission believed that mere participation in a battle justified a death sentence. So in the many cases, perhaps two-thirds of the total, where the prisoner admitted firing shots it proceeded to a guilty verdict in a matter of a few minutes. One can imagine why this happened. The Dakota simply did not understand that their admissions to firing a shot could cost them their lives. In finding these defendants guilty, the commission was merely following orders. Colonel Sibley directed the judges, once they were satisfied that the defendant has "voluntarily participated" in the war, to convict--and to convict on "double quick" time. General Pope, who later reviewed the commission's verdicts, also made no secret of his feelings on the matter. Pope declared that "any Dakota should be executed who was guilty of any sort of complicity in the late outrages."

Somewhat more deliberation was required for trials in which the charge was the murder or rape of settlers, because admissions were much rarer in these cases. After the defendant gave whatever response he cared to make to the charge, prosecution witnesses were called. Where prosecution witnesses contradicted the testimony of the defendant, the commission almost invariably found the prisoner to be guilty. The best witnesses for the prosecution, by a large measure, was Joseph Godfrey, the first prisoner tried, and who had joined forces with the Dakota under duress [GODFREY'S CASE]. Dead settlers cannot testify. Most of the whites who survived the war fled the area. In many cases, that left just Godfrey to testify for the prosecution. Godfrey gave evidence in fifty-five cases and was described by Recorder Isaac Heard as "the greatest institution of the commission." With his "melodious voice" and "remarkable memory" he seemed to Heard "specifically designed as an instrument of justice." [HEARD'S ACCOUNT OF TRIALS]

Godfrey's testimony hurt most defendants, but helped others. For example, when the commission tried mixed-race Thomas Robertson, Godfrey testified: "I don't think Tom is a bad man. I believe he was forced to go." In another case involving a Dakota warrior named Chankahda, Godfrey testified that when other Indians wanted to kill a white woman, "this Indian saved her." In a third case, Godfrey testified that the defendant "always gave good advice. . . He told the Indians that they should not cut the whites' heads off."

In dozens of other cases, Godfrey played the role of quasi-prosecutor. As recorder Isaac Heard put it: "When a prisoner would state he was innocent, and Godfrey knew he was guilty, he would drop his head upon his breast and convulse in a fit of musical laughter." Heard explained that when the commission asked Godfrey to talk to the defendant, he would often "force the Indian, by a series of questions in his own language, into an admission of the truth."

Consider trial #366, the trial of a Dakota named Haypee. Haypee, in his testimony, claimed to have had a lame arm at the time of the raids. He also told the commission that his gun was defective and could not fire. Then Godfrey took over. "Why don't you tell the truth?" he asked. "I saw you go and take the gun of an Indian who was killed and fire two shots. Then you borrowed mine mine and shot with it. You made me reload and you fired again." Faced with Godfrey's accusation, Haypee backed down. "It is true what Godfrey says," Haypee admitted. The commission sentenced Haypee to death.

Remarkably, not a single defendant offered an alibi after Godfrey had placed him at the scene of a shooting. Not a single defendant claimed that Godfrey had identified the wrong man.

In the end, the commission sentenced 303 defendants "to be hanged by the neck until dead." Seventy defendants were acquitted.

Critics have challenged the fairness of the trials. This was a one-of-a-kind set of trials. The usual protections of criminal procedure that defendants in civilian courts enjoy did not apply here. The Dakota had no defense lawyers. They had no one in their corner who could cross-examine prosecution witnesses. They had no one to track down possible defense witnesses. The commission could convict even when one or two members entertained reasonable doubts as to guilt. Convictions sometimes turned on the testimony of a single witness--a witness who might not even have been present when the alleged crime occurred. In addition to raising concerns about the sufficiency of the evidence supporting convictions and the rapidity of trials, critics have charged commission members of harboring prejudice against the defendants. The critics may have a point. The commission members, though men of integrity, were also military men whose troops had recently been under attack by the very men whose cases they were judging. Critics of the trials also have argued that the commission was wrong to treat the defendants as common criminals rather than as the legitimate belligerents of a sovereign power. Finally, they have suggested that the trials should have been conducted in state courts using normal rules of criminal procedure rather than by military commission. [WERE THE TRIALS FAIR?]

The defendants were not the only people for whom the trials were unfair. These were homicide trials without sheriffs, detectives, or coroners. Trials in which witnesses rarely mentioned the names, ages, or apparent causes of death of the victims. One could argue that the Dakota trials were unfair to the victims--victims who were not identified, not even enumerated.

So let's agree that the trials were unfair. Would it be reasonable to expect better? After all, this was the frontier. There were no courthouses in the vicinity. And, in the whole state it seemed, everyone was calling for Dakota blood. Colonel Sibley may well have viewed summary trials by a commission as necessary to avoid vigilante justice by angry mobs of Minnesotans. As it was, the 303 condemned prisoners were attacked in New Ulm on November 9 as they being transported to Mankato to await their execution[SKETCH OF ATTACK IN NEW ULM]. Another planned attack of the prison camp by several hundred armed local citizens on December 4 was foiled by soldiers guarding the Dakota prisoners.

Camp Lincoln

When the trial record arrived in St. Paul, General Pope wasted no time in approving all sentences. He rejected the commission's request for mercy for Joseph Godfrey.

The final decision on whether to go ahead with the planned mass execution of the 303 Dakota and mixed-bloods rested with President Lincoln. General John Pope, having been sent to Minnesota after his defeat at Bull Run, campaigned by telegraph for the speedy execution of all the condemned. He told anyone who would listen that he "is sure" the president will swiftly approve all the sentences. Virtually all of the editorial writers, politicians, and citizens of Minnesota agreed with Pope. One of the few who did not was Henry Whipple, the Episcopal Bishop of Minnesota. Whipple traveled to Washington to meet with Lincoln and discuss the causes of the Dakota Conflict. By Lincoln's own account, the visit impressed him deeply. Lincoln knew well that the lust for Dakota blood could not be ignored; to prevent any executions from going forward might well have condemned all 303 to death at mob hands. The president sent a telegram to General Pope requesting that he "forward as soon as possible the full and complete record of the convictions."

Aware of rumors that many of the convicted men had raped white women, Lincoln ordered two White House lawyers, George Whiting and Francis Ruggles, to make "a careful examination" of the transcripts and identify those "proved guilty of violating females." The aides found exactly two convicted rapists (cases #2 and #4) among the 303 condemned men. Minnesotans would demand more blood than that. Knowing that a decision to permit the execution of only two men would almost certainly lead to a mass lynching of the prisonerss, Lincoln gave Whiting and Ruggles a second order. He asked them to search the records a second time and identify those convicted of participating in the massacres of settlers. The distinction that the commission and General Pope refused to make, and probably should have, Lincoln made for them. This time the aides came up with 40 names. They provided Lincoln with a summary of proof against each man.

Whiting and Ruggles, however, made no point of mentioning the commission's recommendation of mercy for one of the forty, Joseph Godfrey. In early December, the president considered his aides summaries and the transcripts. Then Lincoln hand wrote and execution order listing the name of each Dakota defendant and his case number. Lincoln's list included 39 names--he decided that Joseph Godfrey should live. Lincoln's handwritten order of execution was dated December 6, 1862. [PHOTO OF LINCOLN'S ORDER]

In his report to the Senate, Lincoln explained his decision. He was, he wrote, "anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak of violence, ...nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other hand."

In Mankato, at ten o'clock on a sunny December 26, thirty-eight (one person was reprieved between the date of Lincoln's order and the execution) prisoners wearing white muslin coverings and singing Dakota death songs were led to gallows in a rectangular scaffold and took the places assigned to them on the platform. Ropes were placed around each of the 38 necks. At the signal of three drumbeats, a single blow from an ax cut the rope that held the platform and the prisoners (except for one whose rope had broke, and who consequently had to be restrung) fell to their deaths. A "loud huzza" rose up from the thousands of spectators gathered to witness the event. The bodies were buried in a mass grave on the edge of town. Soon area doctors, including one named William Mayo, arrived to collect cadavers for their medical research. Mayo's sons, both physicians, would later found the Mayo Clinic. [ACCOUNT OF EXECUTIONS]

Epilogue

In April, 1863, Congress enacted a law providing for the forcible removal from Minnesota of all Sioux. Most Dakota, after suffering through a harsh Minnesota winter at a Fort Snelling encampment [PHOTO OF ENCAMPMENT], moved to South Dakota. Prisoners previously held at Mankato were transported on the steamboat Favorite down the Mississippi to Camp McClellan, near Davenport, Iowa.

On March 22, 1866, President Andrew Johnson ordered the release of the 177 surviving prisoners. They were moved to the Santee Reservation near Niobrara, Nebraska.

Little Crow was not among the Dakota tried by the military commission. He, along with 150 or so of his followers, fled to present-day North Dakota and Canada. In June 1863, Little Crow returned to Minnesota on a horse-stealing foray. On July 3, a farmer shot Little Crow while the Dakota chief picked berries with his son near Hutchinson. The farmer received a $500 reward from the state.

The Sioux Wars went on for many years. A military expedition carried the fighting into the Dakota Territory in 1863 and 1864. As the frontier moved westward, new fighting erupted. Finally, in 1890 at Wounded Knee, the generation of warfare that began at Acton, Minnesota in August of 1862 came to an end.

Recently, an effort has been launched to pardon one of the 38 Dakota, a warrior who was wrongfully executed in Mankato in 1862. We-Chank-Washta-don-pee (often called Chaska, the defendant in Case 3) was one of the prisoners whose sentence was commuted by President Lincoln. The evidence at trial showed that Chaska had taken a woman, Sarah Wakefield, and her children prisoner, but had treated them kindly and protected them from other Dakota who would have abused or killed them. Wakefield, testifying before the military tribunal, said: "If it had not been for Chaska, my bones would now be bleaching on the prairie, and my children with Little Crow." Chaska's execution was most likely a mistake, as another convicted Dakota who was scheduled to die, but was spared, had a similar name: Chaskey-etay. (Chaskey-etay had been convicted of murdering a pregnant woman.) A prison chaplain later wrote to Wakefield, distressed over learning of Chaska's death, "Chaska was hung instead of another, I doubt whether I can satisfactorily explain it." Legislation was proposed that would extend a posthumous pardon to Chaska.

Tribal leaders from Minnesota and South Dakota enter downtown Mankato on December 26, 2012 for dedication of a new memorial at the site of the 1862 executions

In Mankato, an old granite monument that simply read "Here were hanged 38 Sioux Indidans--December 26, 1862" has been removed. In its place is a large limestone statue of a bison. The site of 1862 execution has been renamed Reconciliation Park. Each December, scores of members of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe ride on horseback from their South Dakota reservation to Mankato to commemorate the mass hanging. Many non-Indians, some with ancestors who died in the Dakota war, join them.

In thinking about the Dakota trials, my thoughts often return to accounts of the meeting in the White House between Bishop Henry Whipple and President Lincoln. Whipple pushed Lincoln to champion more just and humane treatment of Indians. Of this meeting, Lincoln said, "The Bishop came here the other day and talked with me about the rascality of this Indian business until I felt it down in my boots." Lincoln suggested that once the Civil War was over, he would make better treatment for Indians a priority. If not for a bullet from the gun of John Wilkes Booth, how different--how much better--might have been the history of U.S.--Indian relations?