The Trial of Gilles de Rais (1440): An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2024)

Who was the worst criminal of all time? Asked that question, a reasonable reply might be, “Worst in what way?” The criminal who killed the most people? The criminal who employed the cruelest means of murder? The criminal who chose the most innocent victim? But by whatever measure one chooses, a strong candidate for the worst criminal in history is Gilles de Rais, a French nobleman who, in an eight-year reign of terror in fifteenth-century France, tortured and murdered as many as 200 children (or significantly less than that—the exact number is unknown), mostly boys between the ages of 7 and 15.

That Gilles de Rais, with the help a number of his young accomplices, could go on such a prolonged killing spree without facing a serious investigation, much less a trial, for eight years says a lot about privilege and class in the feudal world of the 1430s. Gilles de Rais was wealthy and connected, with a guard of more than 2oo men, and he carried the title of Marshal of France because of his success in battles with the English during the Hundred Years War, including the key battle to retake Orleans, serving bravely at the side of Joan of Arc. On the other hand, his victims were young and poor—nobodies in the eyes of the privileged class. Child victims, who in many cases made the simple mistake of seeking alms outside the gates of one of the several castles he owned. Who, in a position of power, really cared about these children? Who, in a position of power, would believe them against the word of Gilles de Rais?

Eventually, though, the many dozens of complaining parents and the complaints of a few better-connected people that Gilles de Rais trespassed in serious ways, proved too much for authorities to ignore. He faced trial in 1440. What that trial revealed, through the testimony of Gille de Rais’s accomplices and his own confessions, continues to shock. What Gilles de Rais did in the tower torture rooms of his castles is almost beyond imagination in its depravity.

Background

Gilles de Rais (a.k.a. Gilles de Retz) was born in Champtoce, on the west bank of the Loire, along the border of Brittany and Anjou (in northwestern France), in 1404. His father, Guy de Laval, had recently inherited a vast fortune. All of Gilles’ close relatives were influential feudal lords, owners of large acreages looked over by huge fortresses. The houses from which Gilles came, both on his father’s and mother’s side, were among the noblest and most powerful of his time.

In this privileged world of great lords, no one worked. They might make war against each other, and their fear of the Devil drove might drive them to piety, but mainly they luxuriated in their heavy fortresses, surrounded by servants and men-at-arms ready to respond to their every whim.

Gilles was tutored in his early years by two priests, who taught him Latin and how to read and write. But his education ended abrupted at age eleven, when first his mother, Marie de Craon, and then his father, Guy de Laval, died one after the other in 1415. Under his father’s will, decisions about Gilles’ education were be entrusted to his father’s cousin, as his father apparently feared leaving the course of his son’s future to be determined by his maternal grandfather, a shrewd, but unscrupulous and cruel man.

Despite these stated wishes, Gilles somehow ended up in the care—or more accurately, lack of it—of his grandfather, Jean de Craon. His grandfather taught him the art of extortion and banditry, but little more. Gilles, at the end of his life, attributed his years of evil-doing to the lax education and unbridled idleness that came with living with his grandfather. Gilles said that in his childhood he “pleased himself with every illicit act” and “perpetrated many high and enormous crimes . . . against God and His commandments.”

Only in the combat did Gilles de Rais distinguish himself. In 1427, Craon found a military mentor for his grandson, leading to Gilles’ appointment at a military captain for Duke Louis III of Anjou. Gilles and other French captains led a guerilla campaign against English garrisons, capturing a fortress at Gennes and retaking the castle of Malicorne.

In June of the following year, fresh English troops landed on French soil and laid siege to Orleans. In February of 1429, Joan of Arc met with King Charles VII to promote herself as a champion for France in their holy war against the English invaders. In April, Joan of Arc received authorization from the King to lead a relief army sent to the besieged city of Orleans. Approaching the city, in Blois, the Maid met an escort of several dozen men-at-arms and archers under the command of Gilles de Rais and another military leader.

In May, Rais helped Joan of Arc lift the siege at Orleans, and then joined the Maid in her campaign to recapture English-held towns in the Loire Valley. (The following year, Joan of Arc would be captured by the English, and later be executed.) In recognition of his war efforts, Rais was awarded the rank of Marshal of France. In 1432, Rais lifted the siege of Lagny, near Paris, in one of his most celebrated feats of arms. Although it is speculation, Gilles de Rais biographer, Georges Bataille, argues that the gruesome murders, rape, and pillage associated with military battles of the time facilitated in a way the sadistic violence that became a big part of Rais’ later crimes.

In November 1432, Rais’ grandfather died. Rais participated in a military expedition in 1434, his last, but no fighting resulted. Soon thereafter, Rais seemed to lose interest in military life.

Rais’s family incriminated him for “insane expenses” beginning by the age of 20. How insane? Rais was enormously wealthy in 1432, with an estimated revenues of 800,000 livres. But, within the short span of two years, he managed to lose a considerable portion of his inheritance. According to Baitille, Rais spent “as one drinks liquor, to become giddy.” Traveling often to the city of Nantes, he came accompanied by a guard of 200 men-at-arms, plus numerous esquires, pages, chaplains, singers, and astrologers. In his fortress, where the drawbridge was always raised and the gates closed, he supposedly kept a chapel with silk and gold tapestries and gem-encrusted sacred vessels. In 1435, in an annual celebration of the liberation of Orleans, Rais sponsored “mystery plays” featuring actors in elaborate and expensive costumes, with Rais purchasing new costumes for each play, not wanting them to be used twice. Spectators were served wine and various delicacies, all at Rais’ expense. In 1435, King Charles proclaimed Rais to be under interdict, prohibiting him from entering into contracts for the sale of property, following complaints from his family about his incrediby extravagant spending.

Criminal Life

Beginning in 1432 or late 1433, soon after the death of Gilles’ grandfather, children began disappearing. Bataille speculates that for Rais, the death of his brutal grandfather “must free him, relieve him, and unhinge him at the same time.” Disgraced by the King, Gilles de Rais increasingly withdrew from public life during the mid-1430s to pursue obsessively his own diabolical and sexual interests.

Many of the missing children were last seen begging for alms by the gates of one of Rais’ residences. Servants or cousins of Rais, living at the master’s expense, often met the beggars at the gate and distributed clothes, money, and food. If there was a beautiful boy in the group, he might be promised a treat if they would follow the servant into the castle kitchen. They never came out. Others were last seen running errands to a Rais castle. Or when Rais was staying nearby, young boys were last noticed gathering plums, tending sheep, guarding cows, or chasing butterflies in a woods. Sometimes worried parents approached some of Rais’ people and asked about the whereabouts of their children, only to receive shrugs or be told not to worry—that they will turn up soon enough.

What happened to the children was a mystery. But peasants occasionally reported seeing at night red glares, and hearing cries, coming from a casement high up in a castle tower.

Ruins of the Champtoce castle

In 1438, Rais’ money problems led him to sell his castle at Champtoce for 100,000 gold crowns. But before turning over possession, Rais orders five of his manservants to go to the tower of the fortress and remove the skeletons of approximately forty children. The men place the remains in three coffers and transport them, much of the way by water, to Rais’ castle at Machecoul, where the bones are burned.

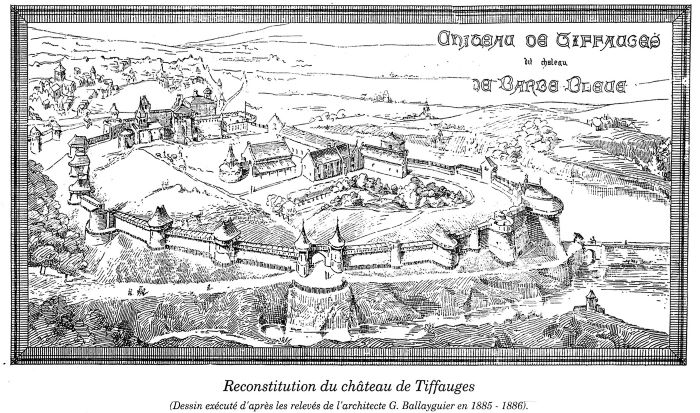

Other than young boys, Gilles de Rais’ other obsession was conjury. Rais participated in ten to twelve rituals in which attempts were made to summon the Devil. One such invocation occurred in the summer of 1439 in his castle at Tiffauges. His conjurer, a charming 22-year-old from Florence named Francois Prelati directed Rais, his priest, and two of Rais’ valets as they traced several circles in the soil with the tip of a sword. Prelati invited anyone who wished to speak and make a pact with the Devil to step inside the circle. Rais willingly did so, holding in his hand a note he signed, should the Devil appear: “Come at my bidding, and I will give you whatever you want, except my soul and the curtailment of my life.” Although “he did everything he could,” Rais reported later that he never actually saw or spoke to the Devil in this or any other invocations—although he became convinced that other participants had.

Rais seemed to attribute the Devil’s hesitation to appear to him to be the result of a dissatisfaction that the Devil had with his behavior. Rais did, however, began wearing around his neck a silver box containing a black powder which his conjurer (and likely lover) told him was a present given by Prelati’s personal demon and intended for Rais. By late fall of the year, at Prelati’s urging and in a desperate effort to make contact with the Devil, Rais prepared an offering, on glass and covered with linen, of the heart and hand (and possibly eyes) of a boy he had just killed.

By early 1440, Rais’ huge personal fortune was virtually exhausted. To raise funds, he sold one of his last remaining castles, Saint-Etienne-de-Mermorte, to a nobleman and the Treasurer of Brittany, a man named Geoffroy Le Ferron. But Rais had second thoughts about the sale of his castle. In an undeniably rash move, Rais attempted to forcibly take back his castle. Rais found that Le Ferron had assigned protection of his purchased castle to his brother Jean, a clergyman protected with ecclesiastical immunity. But Rais refused to let any immunity stop him from bursting, screaming, into the village church where Jean Le Ferron was officiating in a service, dragging the clergyman to the castle, forcing him to open the castle doors, and then putting him in irons.

It was Rais’ wild impulse to retake his castle and hold Jean Le Ferron hostage, not his bloody murder of unnumbered peasant boys (and a few girls), that would prove his undoing. Geoffroy Le Ferron had powerful allies. Before long, the Duke of Brittany enlisted his brother, King Charles VII’s constable, Jean Labbe’, and twenty additional men, to liberate Jean.

Meanwhile, rumors about Rais being responsible for large numbers of missing children became too pervasive for church authorities to ignore. In July 1440, the Bishop Jean de Malestroit of Nantes ordered an investigation. Parents and other relatives of the missing were invited to give either live testimony or prepare depositions. And dozens did. The results of the ecclesiastical investigation were published on July 29.

On September 15, 1440, Gilles de Rais was arrested.

Investigation and Trials

Gilles de Rais surrendered, offering his sword to constable Jean Labbe. The constable unrolled a parchment seal and read the order: Rais was to follow Labbe to Nantes, and there to hear the charges made against him. Horses were saddled and Rais, plus several of his associates, followed the Duke of Brittany’s soldiers along the road to Nantes. Accompanying Rais to prison were alchemist and conjuror Francois Prelati, priest Eustache Blanchet, and valets and partners in crime, Henriet Griart, and Poitu (a.k.a. Etienne Corrillaut).

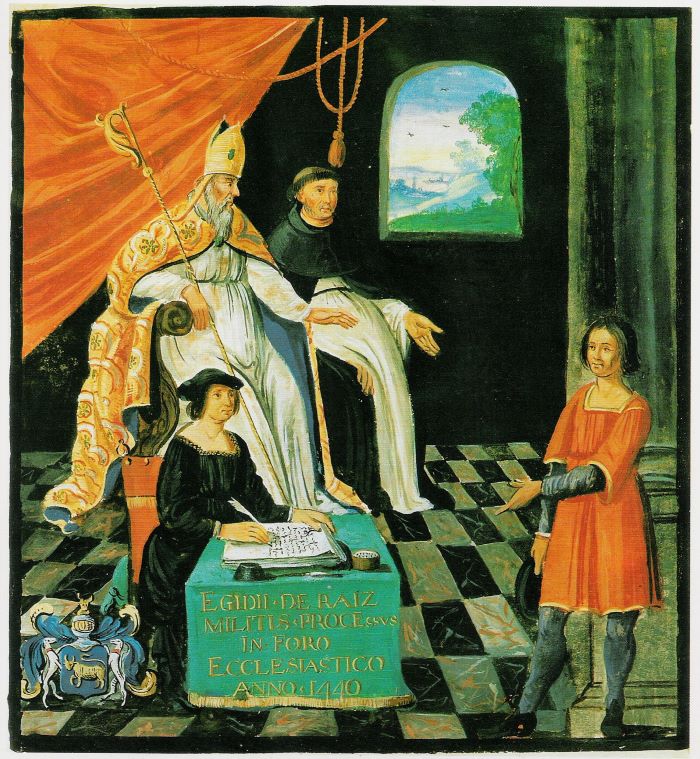

Rais was subject to two proceedings, a secular inquest and an ecclesiastical trial, the two transpiring in parallel. The focus of the two proceedings differed. The secular inquest focused on two criminal charges, the murder of some unknown number of children and Rais’ assault and false imprisonment of clergyman Jean Le Ferron. The ecclesiastical trial, or Inquisition, considered both of those matters, but also raised the issue of “doctrinal heresy” relating to his numerous efforts to summon the Devil and practice magical arts. A secular inquest, ending in a trial, also differs from an ecclesiastical trial in their respective conclusions. Guilt in an ecclesiastical court results in excommunication and makes the accused subject to other lawful punishments. Guilt in the secular trial ends in a specific sentence, likely execution in a case with such serious charges as Rais faced. More-or-less complete records exist of Rais’ ecclesiastical trial, but some of the records of his secular proceedings were destroyed in a fire and what remains is incomplete.

In the secular proceeding on September 15 in Nantes, Rais was read the charges against him, relating to the murder of many children, and his assault and detention of Jean Le Ferron and unlawful occupation of his former castle. Four days later, in the ecclesiastical trial, Rais listened as the prosecutor reads an indictment consisting of 49 articles.

A commissioner appointed to take evidence in the secular inquest, Jean de Toucheronde, opened his investigation on September 18. Each witness who entered knelt before the commissioner, made the sign of the cross, and swore to tell the truth. The first witness, Perrone Loessart, testified that in September 1438, when Rais and his company were passing through her hometown of Roche-Bernard, her ten-year-old son was approached by Poitou. Poitou began chatting with the boy, asking about his ambitions. When the boy said his hope was to become a soldier, Poitou suggested that the child accompany him to Machecoul, where he would taught military skills. Loessart testified that she protested, telling Poitou the boy was doing well in school, but Pontou won permission to carry the boy off after giving her some money. She saw her son off on a horse the next day, tearfully asking Gilles de Rais to treat her son kindly. He made no reply, but Poitu said her son “was as beautiful as an angel.” She never saw her son again.

Witness after witness, in hearings over the course of the next three weeks, told stories of lost children, mostly boys. A common story, told by multiple parents, was of sending their young children off to seek alms at Rais’ castle at Machecoul, only to have them never return.

Other witnesses told stories that implicated Rais or his accomplices. A shoemaker from Machecoul, where parental worries about snatched children were commonplace, testified about the sudden disappearance of a boy last seen picking apples. He said the relatives of lost children were afraid to speak up, fearing violent reprisals from Rais’ men. A woman from the hamlet of La Boucardiere, near Machecoul, testified that she had left her eight-year-old son at home to tend to her infant daughter while she left to plant hemp in a field. When she returned home, she found her daughter, but her son was missing, never to be seen again. Other witnesses told of other disappearances: an eighteen-year-old boy last seen playing with a ball of thread near Rais’ castle; a twelve-year-old who disappeared after being asked by one of Rais’ men to carry a message to the castle; a nine-year-old boy who was tending animals when approached by a Rais accomplice and then never seen again; two boys, ages 15 and 7, sent off to buy bread in Machecoul, but who never returned home. The sad tales went on and on.

Yet other witnesses suggested the fate of the lost children, such as one man who testified that he heard of a conduit filled with dead little children at Rais’ castle of Champtoce. Another woman testified that she heard a woman named Perrine Martin, then detained in a Nantes prison, confess that following the orders of Gilles de Rais, she had led a twelve-year-old boy to Rais’ castle in Machecoul and there turned him over to a porter.

While the secular inquest still continued, Rais appeared in the upper hall of the castle of La Tour Neuve before the Bishop of Nantes and the Vicar of the Inquisition on October 13 to hear the prosecutor in his ecclesiastical trial read a bill of indictment consisting of 49 articles. The articles include allegations that Rais and his accomplices murdered and “shamefully tortured” 140 children, committed heresy by the invocation of demons, and violated ecclesiastical immunity in the seizing and confining of Jean Le Ferron. The indictment lists the places where the child murders allegedly occurred, including the Champtoce castle, the house of La Suze in Nantes, the Machecoul and Tiffauges castles, and other locations. Some murders are specified in detail, including the murder that facilitated the offering of a boy’s body parts in a invocation of demons. The indictment calls for excommunication and “other lawful punishments.”

Rais denied the authority of the ecclesiastical judges. He told them he’d rather be “hanged by a rope around my neck” than respond to their charges. After listening to his rants and refusal to answer the charges, the judges pronounce Rais excommunicated.

But two days later, Rais had second thoughts. Excommunication can have a powerful impact on the faithful. Rais accepted the authority of his judges and admitted that he “maliciously committed and perpetrated” the crimes he was accused of. He “humbly, devoutly, and tearfully” asked the judges to pardon him for his behavior in the previous hearing. The judges accepted the apology and agreed to lift his excommunication. With the excommunication lifted, Rais backtracked again and admitted only to insignificant facts outlined in the bill of indictment.

But the prosecutor in the ecclesiastical trial held all the cards. He called, among nineteen total witnesses, the valets Henriet and Poitu, the conjuror Prelati, Blanchet (Rais’ personal priest), and Perrine Martin, one of Rais’ procurers of children. Their testimony, over the course of the next four days, was shocking and devastating. They described, in sometimes gruesome detail, the torture and murder of dozens of children over the course of years. Never in the history of medieval trials, nor in any trial since, has there been testimony quite so hard to read.

When the witness testimony ended on October 20, the prosecutor asked Gilles de Rais if he had anything to say. Rais responded that he did not. The prosecutor then reminded Rais that he had the power to apply torture “in order to shed light and more thoroughly scrutinize the truth.” The threat worked. He consents to make a full confession, which took place in the castle’s “high room” before a notary and several officials, including cleric Jean de Touscheronde, the official in charge of the secular inquest.

The confession was presented to the Bishop and Vicar of the Inquisition. The officials asked Rais if he had anything more to say beyond what he included in his confession. He at first said no, but then “with great contrition of heart” and “a great effusion of tears,” Rais spilled out every dark secret. He blamed his crimes on the laxity of his upbringing and asked that his confession be printed in French as a warning to all parents. He described the tortured some children by suspending their bodies with cords or on hooks, how he “rubbed” or “erected” the penises of the boys, how he or his accomplices slashed their throats and severed their heads, how he ejaculated and laughed on their dying bodies, how he examined and kissed the most beautiful decapitated heads of the children he killed. Finally, he asked for God’s pardon and the forgiveness of the parents and friends of all the children “I so cruelly murdered.”

When Rais finally finished what must have been a truly stunning speech, the prosecutor set October 25th as the day for “definitive sentences.”

After sentence was rendered, the judges offered a chance to be received back into the Church if he fully confessed his sins. Rais did so in the presence of a monk.

Immediately following the conclusion of the ecclesiastical trial, Rais faced a final reckoning in a secular trial at the fortress of Le Bouffay, where he confessed again, adding a few additional details. Rais was sentenced to be hanged and burned, the sentence to be carried out the next day at eleven o’clock.

On October 26, Giles de Rais, and the previously convicted Henriet and Poitu, were led in a procession from the castle of La Tour Neuve to a meadow beyond the Loire that overlooked Nantes. Accompanying the condemned was an immense crowd, chanting prayers and singing. At the execution site, three gibbets had been erected above three funeral pyres. The tallest gibbet, the one in the middle, was for Rais. Reaching the site, Rais knelt and begged the crowd’s forgiveness.

Just before being led to gibbet, Rais said to his two friends, “We have sinned, all three of us, but as soon as our souls depart our bodies we shall all see God in His glory in Heaven.” Rais was hanged. When the flames burned through the hanging rope, four women “of high rank” rushed forward to snatch his body from the flames and put it into a coffin. Rais was buried in the nearby Church of Notre-Dame-du-Carmel in Nantes. Henriet and Poitu were also hanged, and their bodies burned.