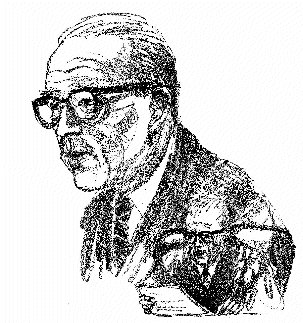

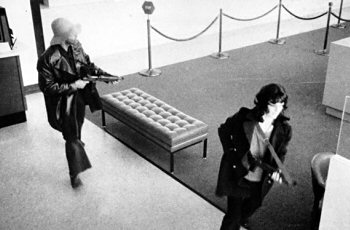

The security camera of the Sunset District branch of Hibernia Bank in San Francisco showed Patricia Hearst holding an assault rifle as members of the Symbionese Liberation Army carried out the midday robbery. Was the rich heiress, kidnapped two months earlier, acting in fear of her life? Was she brainwashed? Or did she participate in the robbery as a loyal soldier in "the revolution"? That was the issue a California jury had to decide in the 1976 trial of Patty Hearst.

On the evening of February 4, 1974, three armed members of a group calling itself the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) burst into the Berkeley, California apartment shared by Patty Hearst and her fiance, Steven Weed. Hearst, the daughter of Randolph Hearst (managing editor of the San Francisco Examiner) and the granddaughter of the legendary William Randolph Hearst, screamed when the men assaulted Weed with a wine bottle. The SLA members carried Hearst, clothed in a nightgown, out of her apartment and forced her into the trunk of a white car. Hearst's abductors fired a round of bullets as they sped away, followed by a second vehicle.

Steven Weed and Patty Hearst (engagement photo)

The SLA released a communique in which it called the kidnapping the "serving of an arrest warrant on Patricia Campbell Hearst." The communique warned that any attempt to rescue Hearst would result in the prisoner being "executed." The statement ended with the capital letters: "DEATH TO THE FASCIST INSECT THAT PREYS UPON THE LIFE OF THE PEOPLE."

Eight days later, the SLA sent a audiotape to a local radio station, KPFA, tape recording from "General Field Marshall Cinque" demanding that Randolph Hearst fund a multi-million dollar food giveaway "as a good faith gesture." "Cinque" was actually Donald DeFreeze, who--following his escape from a California prison in March 1973--organized a group of Berkeley area activists that hoped to spur a revolution. The SLA established as its goals closing prisons, ending monogamy, and eliminating "all other institutions that have made and sustained capitalism." The tape included the frightened voice of Patty Hearst. She is heard telling her parents: "Mom, Dad, I'm okay. I'm with a combat unit with automatic weapons. And these people aren't just a bunch of nuts....I want to get out of here but the only way I'm going to do it is if we do it their way. And I just hope that you'll do what they say, Dad, and do it quickly..." The package received by the radio station also included a photograph showing Hearst, brandishing a carbine and wearing a beret, in front of the SLA's seven-headed cobra symbol.

SLA leader Donald DeFreeze

In response to the SLA demands, Randolph Hearst created the People in Need program and donated about $2 million. The food giveaway program was fraught with problems. In some distribution locations, rioting and fraud hampered efforts, On February 22 at a distribution site in West Oakland, rioting led to dozens of injuries and arrests. In a March audiotape released by the SLA, Patty criticized her father's food distribution efforts: "So far it sounds like you and your advisers managed to turn it into a real disaster."

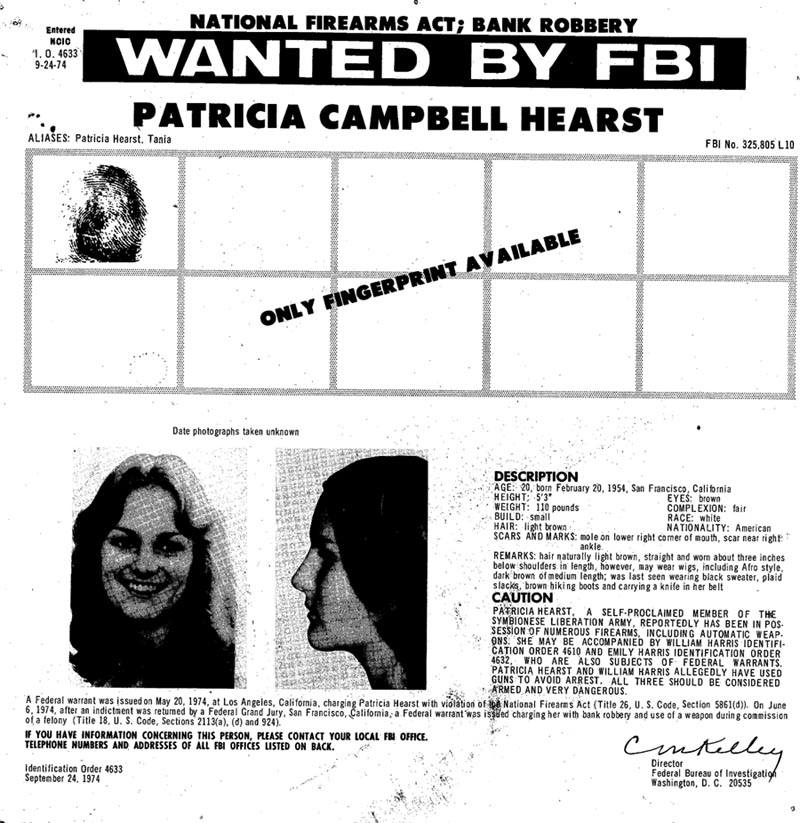

The public heard the most shocking audiotape from the SLA in April, fifty-nine days after Patty's kidnapping. On the tape, Hearst says: "I have been given the choice of being released...or joining the forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army and fighting for my freedom and the freedom of all oppressed people. I have chosen to stay and fight." Hearst further announced that she had accepted the name "Tania," after a "comrade who fought alongside Che in Bolivia."

The Hibernia Bank robbery occurred shortly afterward, on April 15. The robbery, which netted the SLA $10,692, resulted in two bystanders being shot, one fatally. Security camera tapes of the robbery were played on television and closely analyzed by authorities. Different conclusions were drawn from the tapes as to whether Hearst seemed to be a completely willing participant. She can be seen announcing, "I am Tania" and ordering customers to the floor. "We are not fooling around," she warned. In an audiotape released by the SLA after the Hibernia robbery, Hearst says: "Greetings to the people, this is Tania. Our actions of April 15 forced the Corporate State to help finance the revolution. As for being brainwashed, the idea is ridiculous beyond belief. I am a soldier in the People's Army."

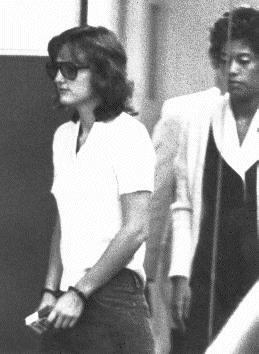

Hearst in Hibernia Bank

A month later, Hearst is at another crime scene, this time at Mel's Sporting Goods Store in Englewood, California. Store employees spotted SLA member William Harris, along with his wife Emily, attempting to shoplift an ammunition case, and a scuffle ensued. From a van parked across the street from Mel's, shots were fired in the direction of the store. The shooter was identified as Patty Hearst.

The "Gotterdaemmerung" came the next day. One hundred Los Angeles police officers mounted an assault on a home at 1466 54th Street, a place determined to be an SLA hideout. The event was captured on live television. Police ordered the home's occupants to "Come on out. Hands up." No one answered the call--except with automatic fire. The heavily armed SLA members succeeded in pinning down the police for a time. In the end, however, teargas grenades started a fire that consumed the house. Six SLA members--a majority of the group's membership, but not included Emily and John Harris or Patty Hearst--died in the assault. Hearst responded by criticizing "the fascist pig media" for "painting a typically distorted picture" of her "beautiful sisters and brothers" killed in the assault. She said that "out of the ashes" of the fire she "was reborn"--and knew what she had to do next.

The arrest of Patty Hearst came over a year later, after authorities following the trail of SLA member Kathleen Soliah (who had not long before organized a commemoration of the gun battle in a Berkeley park) were led to Emily and William Harris and Hearst. Hearst was arrested on September 18, 1975 at her apartment in the outer Mission District of San Francisco. Patty Hearst's mother, Catherine, expressed confidence that her daughter would not face imprisonment: "I don't believe Patty's legal problems are that serious. After all, she's primarily a kidnap victim. She never went off and did anything of her own free will."

The Trial

The trial of Patricia Hearst began on February 4, 1976 (two years to the day after the kidnapping) in the courtroom of U. S. District Judge Oliver J. Carter. The kidnap victim, who had spent fifty-nine days blindfolded and living in a closet where she was subjected to verbal and sexual abuse, was charged with armed robbery of the Hibernia Bank. In the days following her arrest three months earlier, Hearst had maintained her allegiance to the SLA. By the time of the trial, however, she had changed her tune. She claimed she had been brainwashed and feared that had she tried to return to her parents, she would have been killed. Carolyn Anspacher, who covered the trial for the San Francisco Chronicle, offered this assessment of Patty Hearst:

“[T]he metamorphosis back to Patricia, if indeed there was one, took time and platoons of lawyers, as assembled in desperation by the frantic Hearsts... [T]he young woman usually referred to as ‘the defendant’ who will be brought into court to stand trial is a seeming replica of the original Patricia Hearst, the soft-voiced Patty who was wrenched from her familiar surroundings by such violence. . . . Her hair, dyed a brassy red when she was arrested, has been toned to a gentle chestnut and coiffed softly around her face. Her tight and revealing sweater and jeans have been replaced by tasteful slacks and jackets. She no longer lifts manacled wrists in black power salute and her eyes are, for the most part, downcast, as if she were sharing a secret with herself.”

Defense attorney F. Lee Bailey

The defense of Hearst was headed by F. Lee Bailey and his associate Albert Johnson. Bailey chose to adopt the strategy of attempting to prove that Hearst had been "brainwashed" and suffered from what has been variously called the "Stockholm Syndrome" or the "POW Survivor Syndrome." (Although, somewhat inconsistently, Bailey suggested at various times in the trial that his client did only what she had to do to stay alive.) Stockholm Syndrome sufferers are captives who, after a period of being utterly dependent upon the captors, become sympathetic to their captors' cause. Under Bailey's theory, Hearst was never a free agent or voluntary member of the SLA, up to and including the time of her arrest.

The defense strategy of claiming brainwashing and duress, critics pointed out, had several problems. First, the actions and statements of Hearst after the Hibernia robbery strongly suggested that she was acting freely and it was not necessary in the case, critics noted, to establish that Hearst remained brainwashed throughout the entire time up to her arrest--rather only that she was not a free agent at the time of the robbery. Second, brainwashing was not recognized as a defense to bank robbery under federal law, and Judge Carter's instructions to jurors, telling them that Hearst had to have been acting out of an "immediate fear for her life" made acquittal on this theory difficult. Third, the strategy seemed to fly in the face of facts. "Why," a juror might ask, "if Hearst was not a free agent, was she carrying in her purse, on the day of her arrest, a stone Olmec monkey face on a chain given to her by SLA member Cujo (William Wolfe)?" "Why did she have revolutionary books, such as Explosives and Homemade Bombs, on her apartment bookshelf?" "Why did she not escape despite her numerous opportunities to do so?"

Judge Oliver Carter

Judge Carter's ruling undercut the defense strategy by allowing the prosecution to introduce evidence of statements and events after the robbery to prove her state of mind at the time of the robbery. Thus the jury listened to Patty tell Americans on an audiotape, "'The idea of brainwashing is ridiculous." On cross-examination, Hearst faced numerous questions from prosecutors about her actions after the bank robbery, causing her to plead the Fifth Amendment forty-two times. She also had to listen to embarrassing expert testimony about her vulnerability and endure a humiliating cross-examination about a wide range of topics, including her sex life. The strategy, one commentator observed, "deprived Patty of the right to feel blameworthy and get on with her life."

Why, then, did Bailey opt for the brainwashing theory? One reason is because that was the theory that Hearst's parents wanted him to use--and they were paying for his defense. Randolph and Catherine Hearst seemed unwilling to accept that their daughter would voluntarily choose to become an SLA member. Another reason might have been Bailey's fear that arguing in this case that Hearst's voluntary conversion came after the Hibernia robbery would expose her to a future prosecution for her shooting outside Mel's Sporting Goods store a month after the bank robbery. Bailey also had a psychiatrist ready to testify that Patty "was not responsible for her actions" and felt confident of his own ability to sway jurors on the brainwashing theory. Finally, it is possible that Bailey's holding book rights to the Patty Hearst story influenced his decision; brainwashing, it might be assumed, would make for a good story line and boost his recently sagging criminal practice.

In choosing to go forward with the brainwashing theory, defense attorneys rejected the offer of prosecutors to allow Patty to plead guilty to practically anything in return for a lenient sentence, possibly just probation as a first-time offender. Bailey, perhaps, thought he couldn't lose.

Opening statements for the two sides addressed the reality that the crime for which Hearst was being tried was captured on videotape. U. S. Attorney Robert R. Browning quoted from the words of Hearst's April 17 communique: "My gun was loaded, and at no time did any of my comrades intentionally point their guns at me." Bailey, on the other hand, suggested that the robbery was staged by the SLA to make Hearst appear to be an "outlaw." Bailey told jurors, the SLA "positioned her directly in front of the cameras" like "a prized pig." Bailey also argued, "Perhaps for the first time in the history of bank robbery, a robber was directed [by other robbers] to identify herself in the midst of the act." Later, when the prosecution played the security videotape, Patty Hearst gazed disbelievingly at the screen, then began weeping.

Psychiatrists played the central role in Hearst's courtroom drama. Jurors listened to over 200 hours of expert psychiatric testimony. Before the psychiatric testimony began, according to Shana Alexander in Anyone's Daughter: The Times and Trials of Patty Hearst, most jurors thought Hearst was probably innocent--or, at least, not guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Government psychiatrist Joel Fort

No psychiatrist had a bigger effect on the jury's thinking than government psychiatrist Joel Fort. He told jurors to be skeptical of defense psychiatrists, who treat everybody as a patient, not a defendant. He suggested that they have a strong interest in helping Hearst avoid hard time in prison. Moreover, he questioned the ability of defense psychiatrists to draw conclusions about Hearst's state of mind at a time fifteen months before they first interviewed her. According to Fort, Patty Hearst was a prime candidate for radicalism even before her kidnapping. Fort described the young Hearst as basically "an amoral person" who thought rules did not apply to her. He noted that she lied to nuns at school about her mother having cancer in order to get out of an exam, engaged in sexual activity at an early age, and experimented with drugs such as LSD. Fort offered his "velcro theory" for aimless, lost souls such at Hearst: such persons, he said, float around in moral space and then find stuck to them the first random ideology they bump into. It is not at all surprising, Fort concluded, that Hearst would find the SLA appealing. Many of its members, including Cinque, came from educated, upper-class background similar to Patty's--and all chose to become members without being brainwashed. Hearst, if the jurors believed Fort, signed on with the sociopaths as a form of self-hatred.

The decision to go with the brainwashing theory meant that Hearst would have to take the stand to describe in some detail how the brainwashing took place. Unfortunately for her case, the jurors didn't believe a lot of what they heard from her. For example, after Hearst described being "raped" by SLA member William Wolfe (or "Cujo") and telling jurors "I hated him," the prosecution produced the love trinket, the so-called Olmec monkey, found in her purse after arrest, that Wolfe had given her. Asked to explain why she would keep a gift in her purse from a rapist that she hated, Hearst answered lamely that she "like art" and took classes in art history. If the love trinket wasn't enough to explain, there was also Patty's own words in her June 7 communique, in which she called Cujo "the gentlest, most beautiful man I've ever known." In his cross-examination of Hearst, Browning repeatedly turned to the defendant's own writings, in the form of the "Tania Interview" (personal reflections written during Patty's so-called "missing year" with the SLA), to undercut her testimony that she was something other than an enthusiastic radical.

The verdict came after twelve hours of deliberation. Many jurors ended their session in tears. On March 20, 1976, a jury of seven men and five women pronounced Hearst guilty of armed robbery and use of a firearm to commit a felony. In the end, jurors thought Hearst lied to try to shoehorn her actions into an untenable theory. One juror explained that Bailey forced him to either buy or reject "the whole package" and that Hearst's firing shots at Mel's "didn't jive" with her supposedly passive role in the SLA. Hearst was not the weak-willed puppet that the defense suggested she was. A female juror concluded Hearst was "lying, through and through," and that no woman would keep a love token from someone who raped and abused her. Other jurors described Hearst as "remote" and "baffling." We didn't know "whether we were looking at a live girl or a robot," one male juror said. Jurors seemed to blame the defendant for hiding behind Bailey's "mind-control" theory and not coming clean about her true feelings. Hearst's repeated taking of "the Fifth" also didn't sit well with jurors. One explained, "It was a real shocker. A witness can't just tell you what he wants to tell you and not tell you what he doesn't want to."

Epilogue

Hearst was sentenced to seven years in prison. President Jimmy Carter commuted Hearst's sentence to time served in February 1979. Hearst gained her release from prison after just twenty-two months. On January 20, 2001, the last full day of his presidency, Bill Clinton granted Patricia Campbell Hearst a full pardon.

Commentator George Will, reflecting on the Hearst story, saw it as a demonstration of "the fragility of the individual's sense of self." Will observed that Arthur Koestler's classic political novel Darkness at Noon featured a sinister figure named Gletkin who was a master mind bender. Will worried: "The disturbing thought is not that the SLA had some cunning Gletkin who destroyed Tania's sense of her former self. The disturbing thought is that no Gletkin was needed."