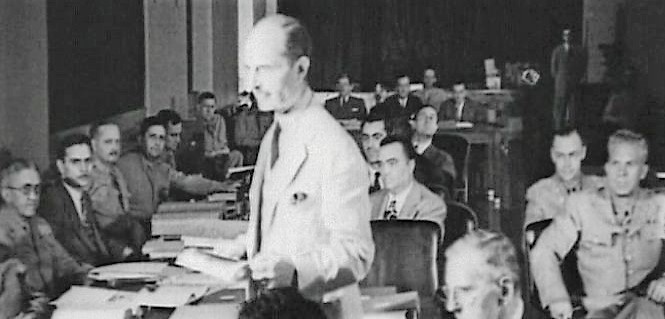

Attorney General Francis Biddle (standing) at the Nazi Saboteurs trial in July 1942.

THE SABOTEUR TRIALS

BY

THE HONORABLE FRANCIS BIDDLE (March 3, 1942)

Dr. Woodward, and ladies and gentlemen: It gives me great pleasure to speak to the Council on Foreign Relations. For nearly ten years I was Chairman of the Philadelphia Branch of the Foreign Policy Association, I take it an organization not unlike yours. General McCoy, who I think lived for some years in Chicago, is now the National Chairman of that organization.

It seems to me that associations of this kind, particularly during the war and during the period when we are discussing post-war problems, can afford a most valuable contribution to public thinking.

I have some hesitation in speaking. One or two of my friends here were good enough to say that they were looking forward to what I was going to say with pleasure. I hope their pleasure will also be present when they look back on it. (Laughter)

I remember a few years ago in Philadelphia I had occasion, at the invitation of the school board, to talk to some girls in a high school there. There were 1500 of them in an assembly hall. I was rather nervous at the appearance of these young ladles, looking at me with a great deal of seriousness, when I talked about the Bill of Rights. I wasn’t sure what kind of impression I had made. But I knew when I received a letter from the Headmistress, who said, "Perhaps you will not consider this as a compliment, but the girls in the special class of intellectually backward and emotionally undeveloped thought that you were the best speaker they had for a long time." (Applause)

I feel sure that what attracted such a large and distinguished audience as is here today was the feeling that the saboteur trial was a good detective story, and I can assure you that it’s a first-rate detective story.

I’m going to talk about it; tell you a little of the circumstances of the trial. Anything I am saying is not taken from the records and the evidence which could not be disclosed; but so much of it has already been disclosed in the reports, and since then, and before then, when the newspaper announcements were first made, that I think what is publicly known makes an interesting story.

You remember there were two submarines that landed on the coast of the United States, The first landed on June 15th, at Amagansett Beach in Long Island; and the second on a beach in Florida, The first saboteur was apprehended on June 20th, precisely a week after the first landing; and the rest of the saboteurs were arrested and in confinement by June 27th.

Now the first we heard of this, which was from a Coast Guardsman who had seen them land in Amagansett, and who had immediately reported to the nearest Coast Guard Station — that, is, about June 14th — was of course immediately relayed by Mr. J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, to me. And from then on we had a very serious problem, which was to decide whether or not we should risk taking time to catch the rest of them — and we thought we could catch them, though we didn’t know how promptly.

We didn’t know how many submarines would land. We didn’t know the extent of the force. And so it was one of those very difficult problems, whether to announce the news immediately, which would give the country warning, put the country on notice, and afford protection to our coasts, or to wait until we could make the case.

Well, we compromised by waiting for a week, and by the end of the week we had all of them; so the problem was solved.

I think the most striking thing about the trial was its speed. You would have been amazed, when the news was made public on June 27th, at the flood of letters that I received saying that it was utterly ridiculous to try these men, that we were wasting precious time; that they should be shot immediately, and that the Department of Justice was showing uncertainty and hesitation in a case of such vital importance.

Now, let me give you the chronology of events. The first landing was on June 13th. The trial began on July 8th and ended on August 3rd. The President announced on August 8th the sentences which the Commission had recommended to him, and announced, at the same time, that the sentences had been carried out. Six of them had been electrocuted; one was sentenced to thirty years, and one was sentenced to life. So that the time in which the case was handle^ was extremely short. The arrest was on June 13th; the case was tried for 17 days, before a Military Commission; the habeas corpus went into a District Court, a Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court, In the Supreme Court the case was argued for two days. The President studied the case for four or five days, and the case was finally finished on August 8th.

Another interesting result was the way the trial of the case created a feeling throughout the country of the officiency and unity of the Government agencies involved.

This is what we did: As I said, on June 27th the last saboteur was taken. We spent the next two days, the 28th and 29th, studying the law, which was exceedingly, complicated and difficult, largely owing to the Milligan Case, to which I shall refer later; and in conferences with the Secretary of War.

It seems to me that associations of this kind, particularly during the war and during the period when we are discussing post-war problems, can afford a most valuable contribution to public thinking.

I have some hesitation in speaking. One or two of my friends here were good enough to say that they were looking forward to what I was going to say with pleasure. I hope their pleasure will also be present when they look back on it. (Laughter)

I remember a few years ago in Philadelphia I had occasion, at the invitation of the school board, to talk to some girls in a high school there. There were 1500 of them in an assembly hall. I was rather nervous at the appearance of these young ladles, looking at me with a great deal of seriousness, when I talked about the Bill of Rights. I wasn’t sure what kind of impression I had made. But I knew when I received a letter from the Headmistress, who said, "Perhaps you will not consider this as a compliment, but the girls in the special class of intellectually backward and emotionally undeveloped thought that you were the best speaker they had for a long time." (Applause)

I feel sure that what attracted such a large and distinguished audience as is here today was the feeling that the saboteur trial was a good detective story, and I can assure you that it’s a first-rate detective story.

I’m going to talk about it; tell you a little of the circumstances of the trial. Anything I am saying is not taken from the records and the evidence which could not be disclosed; but so much of it has already been disclosed in the reports, and since then, and before then, when the newspaper announcements were first made, that I think what is publicly known makes an interesting story.

You remember there were two submarines that landed on the coast of the United States, The first landed on June 15th, at Amagansett Beach in Long Island; and the second on a beach in Florida, The first saboteur was apprehended on June 20th, precisely a week after the first landing; and the rest of the saboteurs were arrested and in confinement by June 27th.

Now the firs we had of this, which was from a Coast Guard who had seen them land in Amagansett, and who had immediately reported to the nearest Coast Guard Station — that, is, about June 14th — was of course immediately relayed by Mr. J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, to me. And from then on we had a very serious problem, which was to decide whether or not we should risk taking time to catch the rest of them — and we thought we could catch them, though we didn’t know how promptly.

We didn’t know how many submarines would land. We didn’t know the extent of the force. And so it was one of those very difficult problems, whether to announce the news immediately, which would give the country warning, put the country on notice, and afford protection to our coasts, or to wait until we could make the case.

Well, we compromised by waiting for a week, and by the end of the week we had all of them; so the problem was solved.

I think the most striking thing about the trial was its speed. You would have been amazed, when the news was made public on June 27th, at the flood of letters that I received saying that it was utterly ridiculous to try these men, that we were wasting precious time; that they should be shot immediately, and that the Department of Justice was showing uncertainty and hesitation in a case of such vital importance.

Now, let me give you the chronology of events. The first landing was on June 13th. The trial began on July 8th and ended on August 3rd. The President announced on August 8th the sentences which the Commission had recommended to him, and announced, at the same time, that the sentences had been carried out. Six of them had been electrocuted; one was sentenced to thirty years, and one was sentenced to life. So that the time in which the case was handle^ was extremely short. The arrest was on June 13th; the case was tried for 17 days, before a Military Commission; the habeas corpus went into a District Court, a Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court, In the Supreme Court the case was argued for two days. The President studied the case for four or five days, and the case was finally finished on August 8th.

Another interesting result was the way the trial of the case created a feeling throughout the country of the officiency and unity of the Government agencies involved.

This is what we did: As I said, on June 27th the last saboteur was taken. We spent the next two days, the 28th and 29th, studying the law, which was exceedingly, complicated and difficult, largely owing to the Milligan Case, to which I shall refer later; and in conferences with the Secretary of War.

June 27th was a Saturday. On Monday morning I reported to the Secretary of War and suggested to him that these men be tried by Military Commission, The problem was how the order setting up the Commission should be drawn, and to what extent any legal steps taken by the prisoners’ counsel which might interfere with our military trial could be blocked off.

These were difficult problems, but the two papers that were vital, the order setting up the Commission and the special proclamation denying these men access to the courts, were drawn within two or three days. The President actually signed the orders on July 2nd, and the trial began six days later, following the rule of courts- martial which provides that at least six days1 notice must be given after the specifications or charges are filed against the prisoners.

Now first let me say a word as to the order setting up the Commission. The laws and regulations governing courts-martial were drawn largely for peace-time, and were chiefly calculated to deal with offenses committed by members of our armed forces. Special commissions had been used, though not very frequently. The last famous one, of course, was the Commission that was set up by President Johnston to try the murderers of Lincoln, Booth was dead when the Commission was set up, but the Military Commission tried and convicted the other conspirators.

Then, before that, General Winfield Scott, in Mexico, had set up a number of commissions to try military offenses; and even before that, during the Revolution, there were several instances of trial by commissions.

The distinction between a Military Commission and court- martial is roughly that a Commission is specially organized for particular circumstances; whereas courts-martial are applicable to the general run of cases, and surrounded by regulations and statutory requirements which were not appropriate to the saboteur case.

For instance, the courts-martial rules provide that every defendant shall have what is called a "peremptory challenge". That means that every defendant has a right to one challenge against the membership of the commission that is trying him, so that any one of these defendants could have challenged the right of any of the Major or Brigadier-Generals to sit on the Commission, How absurd it would have been to permit saboteurs, sent over by the German Reich, to attack our plants, to challenge the authority of their judges without giving any grounds for the challenge.

So that we drew an order which the President signed, that provided the Commission should make its own rules and should not be bound by the usual rules of courts-martial.

I have given you one instance of what those rules are.

There is another rule of courts-martial, for instance, that provides in cases where the death penalty is inflicted a decision of the courts-martial must be unanimous. We saw no reason to apply that rule drawn, as I have said, with the purpose of applying it to men in our armed forces, and we provided, therefore, that a decision of two- thirds of the commission would apply. The commission was

unanimous, and of course there was never any question about any dis agreement.

A further provision in this order that set up the Commission was that the Commission should not be restricted by the usual technical rules applying to the admission of evidence. Specifically it said: "Such evidence shall be admitted as would, in the opinion of the President of the Commission (who was General Frank McCoy, as you know) have probative value to a reasonable man." That seemed to us a wise method of handling the case.

When the trial first started there was a certain conflict as to the extent of the information that was to be given to the press, and there were naturally different views about it.

The Army felt (I think quite properly) that the case should be tried with as little publicity as possible. Of course, a great deal of information with respect to the training of the saboteurs in Germany, and the knowledge of the mechanisms which they had brought with them for the purpose of destruction, was a matter that held certain military secrets. It was finally agreed that General McCoy should give out, twice a day, such news information as would keep the public advised of what was going on. Well, being an old soldier, he gave out darn little. (Laughter) This, for instance, is typical of the type of thing that the President of the Military Commission would give out to the newspapermen who haunted the corridors of the Department of Justice to pick up any possible crumbs on this exciting trial. On July 14th, he revealed this

startling bit of information: "Thus far in the proceedings, a large number of prosecution exhibits, including explosives, clothing, shovels, and documents had been identified and introduced in evidence. There have been presented to the Commission, and accepted in evidence, much information of a military nature, the disclosure of which at this time would not be of interest to the United States. The defense has been permitted to fully cross-examine all Government witnesses. The procedure followed by the Commission had been in general that followed by the military courts."

And so, twice a day, these little bulletins would come down.

We found, after looking around Washington, that probably the best place to hold the trial was in one of the training rooms of the F. B. I. We closed the corridors at both ends and required passes for everybody entering.

The President, in the order setting up the Commission, had provided that the prosecution should be conducted by the Judge Advocate General of the Army, General Cramer, and myself as Attorney General.

I was anxious to have the Department of Justice represented in the prosecution. I suspected that the case get into the Supreme Court, and that I would then have to argue the case. And as those of you who are lawyers here will agree, you have a better chance in your argument if you make your own record, so I wanted to make my record before the Commission.

The President also appointed the counsel for the defendants, in the order; Colonel Royall and Colonel Dowell who were Chief Counsel for seven of them; and Colonel Ristine who represented the defendant Dasch who wished to have separate representation because he thought his case was not like the others.

In the very beginning of the trial a difficult question was posed to counsel for the defendants. The order creating the Commission had provided that they should try the case before the Commission; and yet the Articles of War which provide for the duties of counsel who are assigned to try cases of defendants of this kind, required any officer who was so assigned before a general Court- Martial or a Special Commission to perform such duties as usually devolve upon the counsel for defendants in a civil case..

Now then, Colonel Royall on the one hand had orders to represent them before the Commission; and on the other, the general theory of court-martial was that he should do all he could for them, just as if he had been in civil trial. So, the first question was, did he have a right to file a petition for writ of habeas corpus?

We told him, and he was told when he went to the Secretary of War, that he would have to decide for himself. I think he decided very well. He wrote the President and the Secretary of War that he was going to file a writ of habeas corpus unless he was ordered not to.

Toward the end of the trial Colonel Royall announced that he was going to apply to the Chief Justice for a writ of habeas corpus.

I might say, by the way, in passing that I want to pay a compliment to the way in which Colonel Royall, my adversary, and Cassius Dowell and Major Stone, who is, by the way, a son of the Chief Justice and who had been assigned to the case, represented their clients. They did it with great strength, with great power, with great intelligence, and never for a moment tried to bring in any technical procedure, any procedure that might delay. In other words, they cooperated with the Government in every way they could, unless it interfered with the substantial rights of their clients; and all through the trial, ladies and gentlemen, they were getting excited telegrams and letters, saying: "How dare you represent these saboteur rats who ought to be shot at once!" -- They were but carrying out orders by their superior officers to represent these defendants in the case.

Well, Colonel Royall decided that he would file a petition.

Now, there were two ways of doing that. If he filed a petition for the writ of habeas corpus and the writ was returned in the usual way, the writ would have ordered us to turn over these men, who were under the custody of the' army, to the civil authorities.

This we dicta* t want to do; but I didn’t want to get into a clash between the courts and the military, But I wasn1t going to give them up unless I had to.

So, we devised a method which was exceedingly fair, it seemed to me, in which the question could be tested without changing the possession of the defendants. Royall petitioned the Supreme Court for leave to file a writ of habeas corpus. Chief Justice Stone, I think on account of the fact that his son was associated with the defense, assigned Mr. Justice Roberts and Mr. Justice Black to act on the petition. These Justices refused to entertain the petitions; but the Supreme Court decided to hear argument of the questions involved; and the Chief Justice convened a special session of the court on a few days notice. It was the first time in twenty-two years that the Court had specially met on a particular case during vacation.

There was some suggestion from those who were a little cautious on the side of secrecy that the Court might hear the case in secret and not admit the public. But the suggestion met with very little response, and as always, the Court was open to the public.

We had now reached the point in the trial where all of the Governments evidence was completed and substantially all of the defendants’ evidence. We all agreed that we should do nothing that would delay the case unreasonably. We wanted to have the case decided as promptly as possible, and yet to give these defendants a fair hearing. Only seven of them filed petitions.

Therefore, the Commission adjourned the day the argument was heard in the Supreme Court.

The argument lasted from Wednesday through Thursday, and on Friday the Court met and handed down their decision. We went right back to the Commission, put in the rest of the evidence; and on Saturday the evidence was completed and the record was taken over by General McCoy and the other members of the Commission to the President on the following Monday.

Let me say a word about the argument before the Supreme Court.

The essence of our argument was that these men were actually caught in armed invasion of our country. They had come to our shores in fatigue uniforms of the German Army. They had changed those uniforms before landing in the rubber boats that took them from the submarines, in order that they could penetrate our lines in civilian clothes and not be recognized as enemies. They had then scattered throughout the United States, armed with high explosives*, with time fuses, with machines calculated to control explosions that would create terrific damage. They had been carefully trained in the saboteur school in Germany, and had been given a list of the various places that they were to attack in this country, particularly some of the aluminum plants; some of the stations; some of the operations of the various railroads.

In our way stood the famous case of Ex Parte Milligan. And we had to convince the court either that the facts of modern war made the situation entirely different from what it had been in the Civil War; or secondly., as we argued very vigorously, that the majority of opinions, if construed in the way we believed the case had been construed, was bad law anyway and we asked that it be overruled.

This was the Milligan Case. Milligan was a citizen of the United States who had lived in Indiana most of his life. He had not taken any part in the war. He was not in the Army, or a member of any militia. He was tried before a Military Commission and accused of plotting against the Government, a part of the plot being to steal weapons from the arsenals, to release Federal prisoners; and in general to use obstructive espionage and sabotage methods against the Federal Government, against the United States.

The case was tried before the commission. Milligan was convicted and ordered shot. But the war was over, and the Milligan argument was made in an atmosphere of resentment against powers exercised by the military, Milligan was held to have been improperly tried by the commission, and was released on what amounted to a petition for habeas corpus. Technically it was a slightly different procedure, but the case amounted in substance to that. The majority of the court said no war was being waged in Indiana; that the courts were still open for trials, and as long as that was true, as long as there had been no martial law declared, it was improper for the military to take citizens and try them by a commission. The case didn’t have to go as far as that because Congress had provided in the Act of 1865 that where men had been arrested by the military, the writ of habeas corpus could be suspended, but they had to be tried within a certain fixed time provided by the Act. If the court had said that Milligan had not been tried under the provisions of the Act, and discharged him, the case would not have been questionable. But the majority went very much further. The case was a rather close parallel to ours, because our courts all over the United States were open to the trial of the saboteurs. They could, theoretically, have been tried by civil courts, and therefore the same kind of logic might be applied.

Before coming to the way the court dealt with the argument,

I thought it might interest you to know that the case of our saboteurs was almost precisely like the famous Wolfe Tone Case in England.

Wolfe Tone was an Irish revolutionary. He had plotted during the Franco-British War and during the Revolution in France to organize a rebellion in Ireland against England. He had been to France, and had been commissioned in the French Army, had then come to Philadelphia, where he had raised money and secured some letters of introduction to the Committee of Defense of the Revolutionary Government in France.

He was later captured and taken in a naval expedition in 1798, if I remember correctly, that went from France to England. He was taken by a British man-of-war, was brought to Dublin and tried before a court-martial.

The description of his appearing in court, as contained in the old account, is not uninteresting. It says: "He was dressed in the French uniform with a large and fiercely-cocked hat, with broad gold lace and the Tricolor Cockade, a blue uniform coat, with gold and embroidered collar, and two large gold epaulettes; blue pantaloons, with gold lace garters at the knees, in short boots, bound at the top with gold lace." Wolfe Tone said: "I have led this rebellion. I’m not ashamed of it, but want to be shot, as becomes an officer in the French Army, and a gentleman." But then one of his lawyer friends, without his knowledge perhaps, filed a writ of habeas corpus to have him discharged. The Commission had ordered him hanged, and that the hanging should be given wide publicity.

Before the court heard argument on the writ, Wolfe Tone was so discouraged by the thought that he couldn’t die like a gentleman, that he cut his throat in jail, and died in three or four days before the habeas corpus writ could be decided. So it became an interesting episode that was not very valuable as a precedent. (Laughter)

Curiously enough, the influence of the Milligan case got into England, and several of the courts followed it, but later rejected it.

There are, I argued to the Court, two types of offenses.

One is a crime. A crime is known to the civil courts. That is something which is tried by a jury under our Constitution.

The offense which is' tried by military tribunal is not a crime in the sense that it must be tried in a certain way. It is an offense against the Army. A commission is not fundamentally a court. The commanding officer finds that a spy has lurked behind the lines. Instead of shooting him outright, which he might have the power to do, we have thought it proper, where the man wasn’t actually taken in the commission of the offense but was arrested later, to provide by law that he should be tried before a Commission in a certain kind of way. But that is not a trial for crime, but an investigation to decide whether an offense against the law of war had been committed.

For the first time (and I think very few lawyers know that)

I found that there is no such thing as the law of war. It’s not writ- ten in any statute. It is not found in any special precedent, but

In war. It is like a common law of war. In one or two cases the Supreme Court has recognized the law of war as something that is the basis of a trial before a Military Commission or Court-Martial.

We argued, therefore, that these men had no right to a trial by jury because the law was perfectly clear that if one of our own officers or men had committed an offense against military regulations he would be tried by a court-martial in peacetime or in war, without any jury. Now, how absurd to say that if a German spy, an enemy agent and saboteur, comes over here, he is entitled to a trial by a jury, and that the Constitution was meant to protect him in this manner, We admitted that the international law of war provides certain protection for prisoners conquered in battle; but argued that where a man changes his uniform and puts on civilian clothes and turns into a spy, he has no protection of international law, and should be tried by any military commission the way Major Andre’ was tried.

The court adopted this reasoning and held that the Commission was properly constituted and had power to try these defendants as they were tried, and that the law of war was applicable. Therefore the Court refused to grant the writ.

There was another very interesting aspect of the case, which the Supreme Court didn’t have to pass on, as it had determined the case in the manner that I have suggested; and that is a con-struction of the proclamation which I spoke of a little while ago, but which I haven't explained very much.

The proclamation was founded on an old Act of 1798, which I don't think has been used for many years, but which we dug out.

is exceedingly interesting - prepared, of course, during the Revolutionary War. It provides that whenever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or "where an invasion is threatened or perpetrated then the persons shall be liable to be apprehended". The language seems to contemplate exactly our case. The invasion had been perpetrated by the saboteurs coming over in a submarine. And then the Statute adds this very interesting if slightly ambiguous language: "The President is authorized in such event, by his proclamation or other public act, to direct the conduct to be observed on the part of the United States toward the alien."

We argued that the President has a right under this law to say how the saboteurs should be handled; and we had drawn the proclamation, which the president signed, so that it barred access to the courts by these alien enemies. In other words, we tried to prevent their even getting into the Courts or asserting the rights of habeas corpus, It is an exceedingly interesting question, but the court, as I've said, did not pass on it, and dealt with the case on much broader grounds.

There was the choice possibility of trying these saboteurs either in civil courts or before a Military Commission. Let us look at the possibility of the civil side of such a procedure.

These men, mind you, had landed in the United States and had brought their implements of destruction with them, had buried them in the sand, buried the TNT, the explosives and the fuses. But they had not used them, so there was no crime of sabotage. They could have been punished for thirty years under the anti-sabotage statute.

Very good — was there any attempt to commit sabotage? I think not. When a man buys a gun that doesn’t yet constitute an attempt to murder. There was practically no evidence of espionage. They had a formula for secret writing, but they hadn’t used it.

So, all they had done was to conspire to commit sabotage, and that under the general conspiracy laws of the United States is a crime punishable by imprisonment for two years. How ridiculous it would have been therefore for us to turn these cases over to the civil side of the Government to try.

There were fourteen accessories to the saboteurs. Seven of them were tried and convicted in Chicago, and their case is now on appeal. Several were tried and convicted in New York. But one of the accessories was a man who was told the story of the landings, and who looked after one of the saboteurs, and changed his money - they had between^ them $150,000.00 In $50.00 bills. He was tried in New York for treason, and the judge directed an acquittal on the ground that the Government had not shown sufficient evidence to convict him. He was a German citizen. His name had been given as the contact man for the saboteurs in this country, and he had been active in their help; and yet the court held that the statute did not permit his conviction for treason.

We then indicted him on trading with the enemy, and other similar charges; but crimes under those statutes are not subject to punishment commensurate with the acts that he had committed.

The cases construing treason are ambiguous. There is some doubt whether an alien, though he has lived in this country, can be convicted of treason. The Supreme Court has never ruled on that. But the basis of treason Is disloyalty to your country; and therefore, an alien, perhaps, cannot commit treason; and yet an alien, who does these things, certainly is as guilty as an American citizen who does them. Therefore, it seemed to us advisable to implement the law with a statute which would make properly punishable the kind of offenses of which these saboteurs were guilty.

I recommended the introduction of an appropriate statute in the last session of Congress. It was reported favorably by the Judiciary Committee of the Senate, and of course had to be re-introduced at this session.

It is, I think, an important bill. It is known as the War Security Bill and provides for death where certain offenses are committed; for imprisonment for life or a shorter term, where an attempt or conspiracy to commit those acts, is perpetrated. It pro-vides for a prompt handling of the cases, so that they may go quickly up through the appeal procedure. And it makes a serious offense for any person who knows that the crime is being committed not to report it to the F.B.I. or to the appropriate authorities.

Now, although the sentences are extremely severe, the Act provides in every clause that the actions forbidden must be done with intent to aid a country which is at war with the United States.

The Act has been attacked from a few sources as being Tin- fair, and not preserving civil liberties. It doesn't seem to me that criticism is in any way warranted. The Act defines certain acts of sabotage; certain acts of espionage; the use of certain means of communication, as, for instance, the operation of a radio in this country for short wave abroad - obviously things of the most serious kind, that are not covered properly now by any of the existing laws. Some of its provisions are more narrowly drawn under some existing laws, notably the Espionage

Act of the last war, which is still in effect, where a reasonable ground to believe is made the basis of the criminal intent, whereas in the proposed Act there must be the specific intent of injuring the United States.

I think in all these things, during the war, there is a great responsibility on the-Attorney General, to guard security of the United States in time of war, which seems to me paramount. I am glad to report that with the exception of sabotage in plants from time to time amounting to malicious mischief, which occurs also in time of peace, this saboteur case is the only case of sabotage directed by the enemy since the war broke out, I think that we are well protected by the F.B.I. and by the men in the Army and Navy Intelligence, working in close cooperation with the F.B.I. That is my first responsibility, ladies and gentlemen.

It seems to me, also, that a responsibility of the Attorney General is to prevent the mis-use of the great power of the prosecutor during a war in which men's minds and the minds of juries are not un-naturally often inflamed. It is often easy to convict persons accused of acts against their government during the war, and therefore, we must always remember that if we are given these great powers they must be administered with the sense that the prosecutor must think not only of obtaining a conviction, but must remember that our method of obtaining convictions is to have a fair trial, and that the defendant gets his day in court. The way in which this sabotage case was handled gave evidence that a democracy at war can be prompt and effective, and at the same time can play fair no matter who the accused is. He can be and will be given a fair trial in the courts of this country. (Applause)