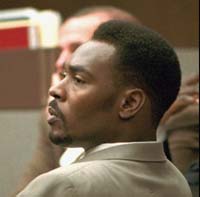

Rodney Glen King (known to friends as "Glen") found himself thrust into the spotlight--both literally and figuratively--after he led California Highway Patrol officers on a high speed chase through the north Los Angeles suburbs. The video of King's beating by LAPD officers, made possible by the overhead illumination of a police helicopter, shocked the nation and led to two criminal trials and a civil trial against the officers.

The beating on March 3, 1991 was not King's first difficulty with the law--and it wouldn't be his last. In 1987, King received probation after pleading "no contest" to charges for beating his wife. Two years later, King received a two-year sentence after robbing a convenience store and assaulting the store clerk. He was paroled on December 27, 1990. In the years following the trials that made him famous, King would again face charges of wife beating (this time his second wife, as well as his out-of-wedlock daughter) and multiple charges of driving while intoxicated.

King's problems with the law stemmed more from his heavy drinking than from any criminal bent. Tim Fowler, King's parole officer, described Rodney as "basically a decent guy with borderline intelligence but [who] could function in society. His problem was alcoholism. He had been drinking from an early age." Friends described King as usually friendly and gentle, but strong-willed and capable of blowing up after drinking.

King was born in Sacramento in 1965. As a boy, Rodney showed considerable athletic promise. He enjoyed fishing with his father. By fourth grade, Rodney was cleaning commercial buildings from 5 P.M. to 2 A.M. with his father. The late night work, according to King, "really whacked" his concentration at school, where he was already suffering because of a learning disability. Teachers reported that King could barely read. He dropped out of school during his senior year.

King found work in the construction industry. Years later, King said, "I got a real thrill out of building skyscrapers." At the time of his well-publicized beating, King was working on a construction project at Dodger Stadium.

King's best moment came after the rioting that came on the heels of the Simi Valley jury's verdict. King went before television cameras to plead for calm. "Can we all get along?" he asked.

King received a $3.8 million award in damages as a result of a civil suit filed against the City of Los Angeles. King used some of the money to start a rap label record business, Alta-Pazz Recording Company. King drowned in his pool in Rialto, California on June 17, 2012, at the age of 47.

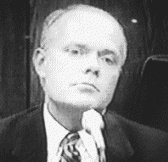

Sergeant Stacey Cornell Koon, the supervising officer at the arrest of Rodney King, wanted nothing so much as to be known as a good cop who did his job in a professional manner. Forty-one at the time of the King incident, Koon believed then--and continued to believe throughout his trials--that his actions may well have saved Rodney King's life. Looking back at March 3, 1991 many years later, Koon said, "I wouldn't change what happened one iota."

Koon was a well-respected fourteen-year veteran of the LAPD with a masters degree in criminology. In his years on the force, he earned over ninety commendations and just three reprimands. His courage was legendary. While working out of the tough South Central district, Koon once witnessed a black transvestite prostitute--who had been brought in for booking--fall over from an apparent heart attack. Even though AIDS was rampant in the city and the prostitute had symptomatic open mouth sores, Koon dropped to the floor and administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. (The prostitute did in fact have AIDS).

Fellow black officers considered Koon to be committed to racial equality. One black officer on the force said of him, "Stacey is a guy you can walk up to and he'll give you the shirt off his back." Koon once investigated a police brutality charge brought against a white officer by two black transients--a charge most officers might have let drop. He even angered many officers by ordering the accused officer to stand in a line-up for identification by the transients. (The officer was later found guilty of using excessive force.)

On the night of March 3, 1991, Koon ordered CHP officers to stand away. He said later he thought the CHP officers' use of drawn guns was "a lousy tactic." Instead, he twice tried tasing King. The ineffectiveness of the Taser convinced Koon that King was "dusted," or on the drug PCP. When the Taser and swarming King proved unsuccessful, Koon, according to one investigator, "looked around and saw a bunch of rookies--he tunneled in."

Koon may have won the case for the defense in the Simi Valley trial. Although Prosecutor Terry White thought Koon to be "an arrogant sonofabitch," he came across as a sincere witness who genuinely believed that the force used against King was managed and controlled. One of the most dramatic moments of the trial came when his attorney Daryll Mounger asked him what he was "thinking at the time you saw Melanie Singer approaching with a gun in her hand?" Koon fought back tears as he answered: "They show you a picture when you are in the Academy [taken] at the morgue, and it is four [highway patrol] officers in full uniform that are on a slab and they are dead, and it is the Newhall shooting."

At the federal trial, Koon revealed none of the emotions that came through in Simi Valley--and that might have sealed his fate. To some observers, he came across as cool or "cocky."

After his conviction in the federal trial, Koon served over two years in federal prison. Shortly before his parole in December of 1995, an unsuccessful attempt was made on his life.

In recent years, Koon--ineligible as a convicted felon to serve on a police force--sought satisfaction in part-time paralegal work and in being a "house husband."

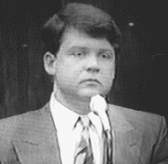

Laurence Michael Powell, age twenty-eight, was the problem officer for the defense. Just hours before the King arrest, the three-year veteran of the LAPD had been called upon at roll call to demonstrate power strokes with his metal baton and had performed poorly enough to have been singled out for inefficient use of his weapon. His ineffective technique also was in evidence in his performance as the lead officer in the King arrest, where he hit King in the face (against LAPD policy), missed with many of his estimated forty swings at King, and failed to pause in his blows long enough to evaluate the effect they were having on the subject. After the arrest, Powell typed into his in-car computer the message: "I haven't beaten anyone this bad in a long time." Another message of Powell's--one sent shortly before the King arrest--also would prove highly embarrassing to the defense. In his message, Powell described the scene of a domestic disturbance involving African-Americans as right out of "Gorillas in the Mist."

Journalist Lou Cannon, author of Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD, described Powell as a "uniformed accident in waiting." Cannon quoted a black officer who said of Powell, "He treated everybody like crap. He always had his hand on his gun." Other officers called Powell "immature" and sexist. Prosecution investigator Jack White called Powell "an overaggressive and slightly sadistic police officer of questionable judgment." Prior to the King incident, Los Angeles had settled one excessive force claim against Powell for $70,000. He had also been identified as striking a handcuffed prisoner and cursing a black motorist simply for driving in a white neighborhood.

Powell's early career on the LAPD was more promising. After graduating as an honor student from Crescenta Valley High School in the San Fernando Valley and taking three semesters of college, Powell enrolled in the Police Academy. He graduated near the top of his class and received praise from a supervisor of his early field work, who called Powell "a hard worker" with a "real positive attitude."

Powell became one of two officers convicted for violating the civil rights of Rodney King. Also, while other officers were acquitted of all state charges by the Simi Valley jury, the jury was unable to reach a verdict in Powell's case. As a result of his conviction, Powell served over two years in federal prison.

After serving his time, Powell had difficulty finding work and chose instead to enrolled in school.

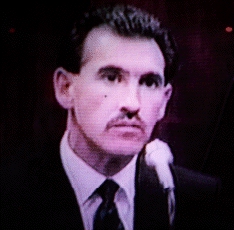

Among the officers who witnessed the King arrest, only Theodore Briseno, a hard-working nine-year veteran of the LAPD, expressed criticism of it before learning of the existence of a videotape. Briseno said to his partner, Rolando Solano, "Sarge really fucked up out there tonight." He added that his fellow officers "should have their asses reamed." In statements to Internal Affairs investigators and in trial testimony, Briseno never wavered from his view that excessive force was used against Rodney King. His criticism of the handling of the King arrest led Stacey Koon to dub the thirty-eight-year old officer "Benedict Briseno."

Briseno had once earlier been charged with using excessive force. In 1987, Briseno was suspended from the force for using force on a handcuffed child abuse suspect. Chastened by the suspension, Briseno never again became the target of an excessive force investigation.

The Holliday videotape showed Briseno step in between King and the baton-swinging Laurence Powell. Briseno said he did so to stop the beating. Powell claimed he did so to warn him to get back so that he not get struck by Koon's electric stun gun.

The only use of force shown on the videotape involving Briseno was a single stomp on King's shoulders at about the time Powell was reaching for his handcuffs. Briseno testified that the stomp was an effort to get King down so that the other officers would stop their clubbing. He said he stomped on King--rather than put his knee on him, as LAPD policy dictates--because he feared getting accidentally struck by a baton if he lowered himself to his knees.

In the Simi Valley trial, defendant Briseno became the prosecution's best witness. He told jurors that he thought Powell "was out of control" and that the beating was "excessive." He said that he yelled to Powell to "get the hell off" King, but that Powell ignored him. "It was like he moved, they hit him," Briseno testified. "I just didn't understand what was going on out there....It didn't make any sense to me."

Acquitted in the Simi Valley trial, Briseno next faced federal charges. Federal prosecutors contemplated not charging Briseno, but concluded his testimony as a defendant might be more persuasive as a defendant than as a witness for the prosecution. Harland Braun, Briseno's attorney in the federal trial, contended that Briseno was named as a defendant "so jurors can condemn Larry Powell and Stacey Koon yet feel good they released someone." Briseno did not appear as a live witness at the federal trial as Braun agreed to lend his support to a unified defense theory. Instead, the jury saw an edited version of his videotaped Simi Valley testimony--which may have been even more damaging to the defense. (It eliminated the possibility of cross-examination.) The jury acquitted Briseno. Jurors were reported to have concluded that Briseno showed himself to be a highly professional officer.

Despite his two acquittals, Briseno was dismissed from the LAPD force. Because of his testimony against fellow officers violated a widely honored "code of silence," Briseno found obtaining work as a police officer difficult. He took a job as a private security officer.

In May 1990 Timothy Wind left his native Kansas, where he had worked for seven years on a suburban police force, because, he said, "I wanted to work for the best." A promising thirty-year-old rookie cop at the time of the Rodney King incident, Wind is often seen as a victim.

Evaluators at the Los Angeles Police Academy called Wind "highly motivated, eager to learn, and extremely safety conscious." After completing work at the Academy, Wind was assigned a position as a probationary officer in the Foothill Division. Supervisors reported that he demonstrated "good judgment in dealing with violent suspects."

At the time of the King arrest, Wind was working his third day in a car with Officer Laurence Powell. Although tarred because of the racist "Gorillas in the Mist" message sent from the Powell-Wind car, Wind was anything but a racist. He later described the message sent by Powell as "immature, irresponsible, and unprofessional."

In the Holliday video, Wind is seen kicking King (six times) and striking King with his baton numerous times. The baton blows were in response to instructions by Sergeant Stacey Koon to deliver power strokes against King. The kicks were later determined to be a violation of police department policy. The video also shows Wind stepping back from King after delivering blows, presumably to evaluate their impact as he was instructed at the Police Academy.

After the arrest, Wind told his story to Internal Affairs investigators. He remembered everything and answered every question. His account was the one most consistent with the videotape.

For his role in the King arrest, Wind was tried twice, once in Simi Valley on state charges and once in federal court. He was acquitted in both trials.

Nonetheless, Wind's connection with the King case made his life very difficult. He faced large debts, joblessness, personal threats, and three stress-induced surgeries. Fired in 1994 by Police Chief Willie Williams, Wind took work as a community service officer in Culver City, California.