The verdict of "not guilty" for reason of insanity in the 1982 trial of John Hinckley, Jr. for his attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan stunned and outraged many Americans. An ABC News poll taken the day after the verdict showed 83% of those polled thought "justice was not done" in the Hinckley case. Some people--without much evidence--attributed the verdict to an anti-Reagan bias on the part the Washington, D. C. jury of eleven blacks and one white. Many more people, however, blamed a legal system that they claimed made it too easy for juries to return "not guilty" verdicts in insanity cases--despite the fact that such pleas were made in only 2% of felony cases and failed over 75% of the time. Public pressure resulting from the Hinckley verdict spurred Congress and most states into enacting major reforms of laws governing the use of the insanity defense.

The Hinckley trial highlights the difficulty of a system that forces jurors to label a defendant either "sane" or "insane" when the defendant may in fact be close to the middle on a spectrum ranging from Star Trek's Mr. Spock to the person who strangles his wife thinking that he's squeezing a grapefruit. Any objective evaluation of John Hinckley's mental condition shows him to be a troubled young man--not, as one prosecution witness described him, "a normal, All-American boy." But how troubled? The prosecution contended that Hinckley suffered only from "personality disorders" of the type affecting five to ten percent of the population, whereas the defense saw the same evidence as demonstrating Hinckley's serious mental illness.

The Hinckley trial, perhaps better than any other famous trial, reveals the difficulty of ascertaining what exactly is going on in the head of another human being--and then in using that imperfect knowledge to answer a legal question that reduces complex and changing mental states to two oversimplified categories.

THE TROUBLED LIFE OF JOHN HINCKLEY

The youngest of three children born to a workaholic oil executive and an agoraphobic stay-at-home mother, John Hinckley from an early age was clingy and very dependent upon his mother. Reviewing Breaking Points, JoAnn and Jack Hinckley's book about their coming to terms with their son's mental illness, Laura Obolensky writes--too critically, perhaps--in The New Republic of life inside the affectless Hinckley home:

Perhaps it is fear of what lies outside that makes the interior of the family so rigid and subdued, like life in a well-run bunker. The world of the Hinckleys was the rootless, middle-class Sunbelt culture that nurtures pro-family values, Christian fundamentalism, and occasional mass murderers. Families move frequently, but without compromising their parochialism. Everywhere, people are white, Christian, Republican (JoAnn explains John's egregious prejudices by saying he had "never been around people of other races.") Somewhere outside there are malign elements--minority groups, rock musicians, big government, and the cynical, Godless cosmopolites who dominate the media. Mothers in this culture do not lavish attention on their children, but on their furniture.

Hinckley drifted aimlessly through two years of college at Texas Tech, in Lubbock, playing his guitar, listening to music, and watching television. In the spring of 1976, he dropped out of school and headed for Hollywood, where he hoped--despite a lack of musical education--to make it as a songwriter.

While in Hollywood Hinckley first viewed a movie,Taxi Driver, that seemed to give dramatic content to his misery and meaning to his life. Fifteen times over the next several years he watched this tale of a psychotic Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle (played by Robert DeNiro), who contemplates political assassination and then rescues--through violence--a vulnerable young prostitute, Iris (played by Jodie Foster), from the clutches of her pimp. In the movie, Hinckley seems to find clues to escape his depression. He begins to adopt the dress, preferences, and mannerisms of the Bickle character. Like Bickle, Hinckley begins keeping a diary, wearing an army fatigue jacket and boots, drinking peach brandy, and develops a fascination with guns. In letters to his parents in Evergreen, Colorado, Hinckley describes a fabricated relationship with a "Lynn," who shares many characteristics with Bickle's initial love interest in the movie, a campaign worker named "Betsy" (played by Cybill Shepherd). Most significantly, however, Hinckley begins a long-term obsession with actress Jodie Foster.

Jodie Foster as "Iris" in the movie Taxi Driver

In the spring of 1977, admitting defeat in his attempt to launch a musical career, Hinckley returned Texas Tech, where he sporadically attended class and spent most of his time alone. Over the next two years, Hinckley's parents expressed increasing concern to their son about his occupational goals. His depression deepened. Life seemed to lack purpose. In August, 1979, he bought his first gun and took up target-shooting. Two times that fall he played "Russian Roulette." By Christmas of 1979, fear of facing his family caused him to spend the holiday by himself in Lubbock. A photo Hinckley took of himself in early 1980 shows him holding a gun to his temple.

In the summer of 1980, Hinckley informed his parents that he had a new career goal, writing. He asked his parents to pay for writing course at Yale. Hinckley never intended to enroll in writing course; his interest in visiting New Haven centered on one of Yale's undergraduates: Jodie Foster. With $3,600 of his parents' money and promising to work diligently at Yale, Hinckley set off for Connecticut on September 17.

Not surprisingly, Hinckley failed in his efforts to win the love of Jodie Foster. Too shy to approach her in person, Hinckley left letters and poems in her mailbox and talked to her twice--awkwardly--over the phone.

Soon after his disappointment at Yale, Hinckley began to stalk President Carter at campaign appearances. In a three-day period, Hinckley visited three cities where Carter rallies were held: Washington, D. C., Columbus, and Dayton. Although assassinating the President was clearly on his mind, Hinckley explained later that at that time he was unable to get himself into "a frame of mind where he could actually carry out the act." Video taken in Dayton showed Hinckley to have gotten within twenty feet of the President.

For the next few weeks, Hinckley continued to fly frenetically around the country. He reappeared in New Haven, then flew to Lincoln, Nebraska on October 6, where he hoped to meet with "one of the leading ideologicians" of the American Nazi Party. The hoped-for meeting never took place. From Lincoln it was on to Nashville, for another Carter campaign stop. Security officers at the Nashville airport arrested Hinckley for carrying handguns in his suitcase, and confiscated both the guns and handcuffs also found in his luggage. Hinckley paid a fine and was released. After yet another short visit to Yale, Hinckley flew to Dallas, where he purchased more handguns. Then Hinckley boarded a flight for Washington, continuing his trailing of Carter.

On October 20, his $3,600 exhausted, Hinckley flew home to Colorado, where his parents expressed strong disappointment in his failure to carry out his promises. After Hinckley overdosed on antidepressant medication, the Hinckleys arranged for their son to meet with a local psychiatrist, Dr. John Hopper. Hopper met with Hinckley several times over the course of the next four months, but learned nothing of Hinckley's thoughts of assassination and little of his obsession with Foster. Hopper urged JoAnn and Jack Hinckley to push John toward emotional and financial independence.

Hinckley's mental health did not improve--rather, it deteriorated. He continued flying across the country to Washington (where the new President-Elect, Ronald Reagan, was staying), New York (where John Lennon had just been assassinated), and New Haven. While in New York, Hinckley seriously contemplated killing himself in front of the Dakota Hotel, at the exact spot where Lennon had been shot. On New Year's Eve of 1980, Hinckley recorded a deeply disturbing monologue in which he spoke of not "really" wanting "to hurt" Jodie Foster, his fears about losing his sanity, and the likelihood of "suicide city" if he failed to win Foster's love.

Hinckley returned to Colorado for his last time on March 7, 1981. Jack Hinckley met John at the Denver airport and told John--having failed to obtain a job--he would not be allowed to go home to Evergreen. Jack Hinckley gave his son $200, which John used to pay for motel rooms in Denver where he sat alone watching television and reading.

Hinckley--unbeknownst to his father--interrupted his stays in cheap motels to visit his mother several times. On March 25, JoAnn Hinckley drove John to the Stapleton Airport in Denver. They drove in virtual silence. At the curbside in front of the terminal, as he reached for his suitcase John said to his mother, "I want to thank you, Mom, for everything you've ever done for me, all these years." JoAnn Hinckley felt fear "climb into my throat" as she replied, "You're very welcome."

THE ASSASSINATION

After a one-day stay in Hollywood and a cross-country trip by Greyhound Bus, Hinckley checked into the Park Central Hotel in Washington, D. C. on the afternoon of March 29. After a restless night, Hinckley rose the next morning for a breakfast at McDonald's. On the way back to the hotel, he picked up the Washington Star. Hinckley noticed the President's schedule, on page A-4, indicating that Reagan would be speaking to a labor convention at the Washingon Hilton in just a couple of hours. Hinckley showered, took Valium to calm himself, loaded his twenty-two with exploding Devastator bullets purchased nine months earlier at a pawn shop in Lubbock, then wrote a letter to Jodie Foster. The Foster letter shed light on the bizarre motive for Hinckley's plan:

Dear Jodie,

There is a definite possibility that I will be killed in my attempt to get Reagan. It is for this very reason that I am writing you this letter now.

As you well know by now I love you very much. Over the past seven months I've left you dozens of poems, letters and love messages in the faint hope that you could develop an interest in me. Although we talked on the phone a couple of times I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself. Besides my shyness, I honestly did not wish to bother you with my constant presence. I know the many messages left at your door and in your mailbox were a nuisance, but I felt that it was the most painless way for me to express my love for you.

I feel very good about the fact that you at least know my name and know how I feel about you. And by hanging around your dormitory, I've come to realize that I'm the topic of more than a little conversation, however full of ridicule it may be. At least you know that I'll always love you.

Jodie, I would abandon this idea of getting Reagan in a second if I could only win your heart and live out the rest of my life with you, whether it be in total obscurity or whatever.

I will admit to you that the reason I'm going ahead with this attempt now is because I just cannot wait any longer to impress you. I've got to do something now to make you understand, in no uncertain terms, that I am doing all of this for your sake! By sacrificing my freedom and possibly my life, I hope to change your mind about me. This letter is being written only an hour before I leave for the Hilton Hotel. Jodie, I'm asking you to please look into your heart and at least give me the chance, with this historical deed, to gain your respect and love.

I love you forever,

John Hinckley

At one-thirty, Hinckley took a cab through a light drizzle to the Hilton.

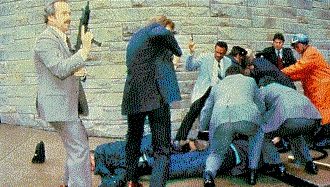

The President waved to a crowd as he walked toward the hotel entrance at 1:45. Hinckley waved back. At 2:25, accompanied by aides and bodyguards, Reagan left the hotel and began moving towards his waiting limousine. A voice yelled, "President Reagan, President Reagan!" As the President turned in his direction, Hinckley--crouching like a marksman--emptied the six bullets in his gun in rapid succession. The first bullet tore through the brain of press secretary James Brady. The second his policeman Thomas Delahanty in the back. The third overshot the President and hit a building. The fourth shot hit secret service agent Timothy McCarthy in the chest. The fifth shot hit the bullet-proof glass of the President's limousine.

The sixth and final bullet nearly killed the President. As aides rushed to push Reagan into his car, the bullet ricocheted off the car, then hit the President in the chest, grazed a rib and lodged in his lung, just inches from his heart. At first it was assumed that the bullet missed the President, and the limousine headed for the White House. Within seconds, however, the President began coughing up blood and the limousine changed course and sped for George Washington University Hospital, where the President underwent two hours of life-saving surgery.

Hinckley was still clicking the trigger on his twenty-two when secret service agents wrestled him to the ground. An agent recalled a "desperate feeling of 'I've got to get to it and stop it.'" as he came down on Hinckley with his right arm around his head.

THE TRIAL

With dozens of witnesses and the shootings captured on videotape, the government knew as well as John Hinckley's own defense lawyer, Vince Fuller, that the only plausible defense was the insanity defense. After a brief detention at the Marine base in Quantico, Virginia--where Fuller first met Hinckley--, he was transferred to a federal penitentiary in Butner, North Carolina. Fuller informed Hinckley's parents of the reasons for the move: "They want to do a psychiatric evaluation, and Butner has the facilities." Over the next four months, psychiatrists for both sides probed nearly every aspect of Hinckley's life.

When the psychiatric reports came in, there were no surprises. All the government psychiatrists concluded that Hinckley was legally sane--that he appreciated the wrongfulness of his act--at the time of the shooting. All three defense psychiatrists diagnosed Hinckley as psychotic--and legally insane--at the time of the shooting. Further evidence of the severity of Hinckley's mental problems came in May, two days before his twenty-sixth birthday, when he attempted suicide by overdosing on Valium. In November, he tried again--this time hanging himself in his cell window.

Hinckley insisted that his lawyers get Jodie Foster to testify in his trial. If they didn't make every effort to do so, he said, he would refuse to cooperate in his own defense. Eventually, Fuller arranged with Foster's lawyer to have the actress testify in a closed session with only the judge, lawyers, and Hinckley present. The tape could later be introduced into evidence at the trial. When Hinckley received the news he excitedly told his parents, "Mom! Dad! I'll be right there in the same room!"

On March 30, 1982, authorities took Hinckley to the federal courthouse in Washington for Jodie Foster's videotaped testimony. The testimony sorely disappointed Hinckley, who received not a single glance or word on his behalf from Foster. As Foster completed her testimony, Hinckley hurled a ballpoint pen at her and yelled, "I'll get you Foster!" Marshals surrounded Hinckley and hauled him from the room.

Jury selection for the Hinckley trial began on April 27, 1982. Selected from a pool of ninety potential jurors were eleven blacks and one white, seven women and five men.

The first phase of the prosecution case, uncontested by the defense, established the obvious: that a shooting had occurred and that Hinckley had done the shooting. Early prosecution witnesses included two of Hinckley's victims, police officer Thomas Delahanty and secret service agent Timothy McCarthy, and a neurosurgeon who described the path of Hinckley's bullet through the brain of James Brady. Prosecutor Roger Adelman also attempted to show premeditation by introducing video footage showing Hinckley's face in a crowd at a Carter campaign rally in Dayton and producing an attendant at a Colorado rifle range who testified that Hinckley engaged in target practicing there in December, 1980.

When the prosecution rested its formal case, the real trial--the insanity trial--began. Defense attorney Vince Fuller opened by asking JoAnn Hinckley about John's childhood, his letters to home from Texas Tech about the imaginary "Lynn," missing money (presumably stolen by John) from Jack Hinckley's study. In cross-examination of JoAnn Hinckley, Assistant U. S. Attorney Robert Chapman tried to establish through his questions that Hinckley couldn't have been too sick--or his parents would have known about it. Why, Chapman wanted to know, did JoAnn Hinckley in the months before the shooting tell John's psychiatrist, Dr. Hopper, that "things are fine."

Jack Hinckley testified about his decision to cut off John's financial support. He told about the day in Denver when he left him to find a cheap motel and try to make a life: "O.K., you are on your own. Do whatever you want to do." Jack Hinckley said, "Looking back on that, I'm sure that it was the greatest mistake in my life." He tried to take the blame for what happened: "I am the cause of John's tragedy--I forced him out at a time when he simply couldn't cope. I wish to God that I could trade places with him right now."

Dr. John Hopper, wearing aviator glasses and talking in a weary tone, testified about his misdiagnosis of Hinckley. John was not merely an "unmotivated kid who needed behavioral therapy," as he first thought, but someone suffering from serious mental illness. An autobiography written by John in November 1980 at Hopper's request was introduced into evidence. In it, Hinckley wrote of "a relationship I had dreamed about" that "went absolutely nowhere" and a mind that was "on the breaking point." Hopper, relying on his face-to-face judgment of Hinckley, had failed to appreciate the seriousness of the warnings contained in the autobiography. Hopper also testified that he knew nothing of Hinckley's stalking of President Carter or his purchase of handguns.

As technicians set up television sets at various locations in the courtroom, Judge Barrington Parker told the jury: "Ladies and gentleman, at this point in time you will see a video tape rendition of a deposition of the witness Jodie Foster." At the defense table, John moved from his habitual slump to an upright position. Foster described Hinckley's first sets of letters to her as "lover-type letters." The last batch of letters Foster called "distress-sounding" and she said "I gave them to the dean of my college." One letter, dated March 6, 1981, said only: "Jodie Foster, love, just wait. I will rescue you very soon. please cooperate. J.W.H." Asked whether she'd "ever seen a message like that before," Foster replied, "Yes, in the movie Taxi Driver the character Travis Bickle sends the character Iris a rescue letter." Then came a series of questions that caused Hinckley to stand and bolt through the courtroom door--pursued by federal marshals:

"Now with respect to the individual John W. Hinckley, looking at him in the courtroom today, do you recall seeing him in person before today?"

"No."

"Did you ever respond to his letters?"

"No, I did not."

"Did you ever invite his approaches?"

"No."

"How would you describe your relationship with John Hinckley?"

"I don't have any relationship with John Hinckley."

After Foster's videotaped testimony, the defense case continued with the introduction of tapes of brief phone conversations with Jodie Foster found in Hinckley's Washington hotel room. The tapes revealed a puzzled Foster trying to put a quick end to the call: "I can't carry on these conversations with people I don't know."

The lead psychiatric expert for the defense was Dr. William Carpenter. One commentator described Carpenter as looking like "Father Time " with his gray beard and shoulder length hair. From forty-five hours of conversation with John Hinckley, Carpenter concluded the defendant suffered from schizophrenia. He saw Hinckley as having four major symptoms of mental illness: "an incapacity to have an ordinary emotional arousal," "autistic retreat from reality," depression including "suicidal features," and an inability to work or establish social bonds.

Defense psychiatrist William Carpenter

According to Carpenter, Hinckley's lack of conviction about his identity led him to snatch fragments of personality from book and movie characters--such as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. As he played his guitar alone in dormitory and hotel rooms, Hinckley had come to think of himself as John Lennon--and thus was thrown into mental chaos by Lennon's sudden death. The monologue Hinckley recorded on New Year's Eve showed the depth of his confusion:

John Lennon is dead. The world is over. Forget it. It's just gonna be insanity, if I even make it through the first few days. . . . I still regret having to go on with 1981 . . . I don't know why people wanna live . . . John Lennon is dead. . . I still think-I still think about Jodie all the time. That's all I think about really. That, and John Lennon's death. They were sorta binded together...

When Jack Hinckley refused to let their son come back home in 1981, John's last link to the real world was severed, Carpenter testified. At his low-rent hotel, Hinckley signed the guest register, "J. Travis." with normal moorings lost, Hinckley followed the "dictates from his inner world." He felt compelled to "rescue" Jodie Foster. According to Carpenter, "He feels like he is on a roller coaster, and cannot escape." Carpenter saw in the shooting of Reagan thoughts of suicide: "His state of mind during the time is depression, the need to terminate all of this, to have his own death." He noted that Hinckley "personalized" Reagan's wave--he thought it was a wave just to him, when it was actually intended for the crowd--, and said that seeing personalized messages in ordinary events was a classic symptom of mental illness.

Carpenter ended three days of testimony by concluding that Hinckley could appreciate the wrongfulness of his act "intellectually," but not emotionally. To him, the President and the others he shot were just "bit players." So focused was he on achieving a "magical unification with Jodie Foster" that he didn't see the consequences of his action for his victims.

Dr. David Bear joined in Carpenter's diagnosis of psychosis. He testified that Hinckley thought Travis Bickle was talking to him. He began to feel "like he was acting out a movie script." It was highly unlikely that Hinckley was faking illness, because those that do almost always report fake "positive" signs like hearing voices of having visions. Hinckley's signs were all "negative," like showing no emotion and jumping in his thought. Hinckley's shooting of the President, according to Bear, was "the very opposite of logic." Finally, Bear suggested that a CAT scan of Hinckley showing widened sulci in his brain was "powerful" evidence of his schizophrenia: about one-third of schizophrenics have widened sulci, but only about 2% of the normal population.

Dr. Ernest Prelinger, a Yale psychologist, testified concerning testing he performed on Hinckley. With an I. Q. of 113, Hinckley could be classified as "bright normal." But on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, Hinckley was near the peak of abnormality. According to Prelinger, only one person out a million with Hinckley's score would not be suffering from serious mental illness.

A complete showing of the movie Taxi Driver closed the defense case.

The prosecution, in its psychiatric evidence, attempted to shift the focus of the jury back to March 30, 1981. The government's lead expert, Dr. Park Dietz, put forward the diagnosis of the government's psychiatric team: Hinckley suffered from various personality disorders, but was not psychotic or insane. Essentially, Hinckley was a bored, spoiled, lazy, manipulative rich kid. The teams' report concluded:

Mr. Hinckley's history is clearly indicative of a person who did not function in a usual reasonable manner. However, there is no evidence that he was so impaired that he could not appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.

Dietz had a contradictory interpretation of nearly every piece of a defense evidence. Hinckley's frequent flying showed an ability to make complex travel arrangements more than it did an insane obsession. His choice of Devestator bullets, his concealing of his handgun, and his timing of his assassination attempt showed planning. Hinckley imitated Travis Bickle much as would the fan of rock star--he didn't "absorb" his identity as the defense contended. Hinckley did not have an "obsession" with Foster, but only the sort of infatuation a young man might often have for a starlet. His bizarre writings were "fiction" that were "not that useful" in determining his mental state.

Dietz testified that Hinckley viewed his actions on March 30 as successful. "It worked," Hinckley told Dietz in an interview. "You know, actually, I accomplished everything I was going for there. Actually, I should feel good because I accomplished everything on a grand scale....I didn't get any big thrill out of killing--I mean shooting--him. I did it for her sake....The movie isn't over yet."

After the testimony of another psychiatric expert, Dr. Sally Johnson, who confirmed Dietz's basic findings, Adelman announced, "Your honor, the prosecution rests."

Prosecutor Roder Adelman

Closing arguments contained moments of drama. Adelman, in the government's summation, strode back and forth in front of the jury with the actual gun used in the shootings as he shouted to the jurors, "This man shot down in the street James Brady, a bullet in his brain!" Defense attorney Vince Fuller's recounting of Hinckley's "pathetic" life left John crying at the defense table, his face in his hands, bent forward, and shaking.

Judge Barrington Parker ended eight weeks of evidence and arguments by reading his instructions to the jury. Most importantly, Parker told the jurors that the prosecution had the burden of showing beyond a reasonable doubt that Hinckley was not insane: that on March 30, 1981 he could appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions. Parker did not tell the jury it should reach its conclusion by focusing solely on Hinckley's intellectual awareness of the wrongfulness of his action, as the prosecution suggested, or by some broader notion that included emotional appreciation of wrongfulness.

For over three days the jury deliberated Hinckley's fate. Finally, a verdict. Judge Parker asked the twenty-two year-old jury foreman to unseal the envelope containing the verdict and hand it to a clerk, who passed it to the judge. Parker read the verdict: "As to Count 1, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity. As to Count 2, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity." The reading continued, the same verdict for each of the thirteen counts.

INSANITY DEFENSE REFORM IN THE TRIAL AFTERMATH

Within a month of the Hinckley verdict, the House and Senate were holding hearings on the insanity defense. A measure proposed by Senator Arlen Specter shifted the burden of proof of insanity to the defense. President Reagan expressed his support for the measure with the comment, "If you start thinking about even a lot of your friends, you would have to say, 'Gee, if I had to prove they were sane, I would have a hard job.' "

Joining Congress in shifting the burden of proof were a number of states. Within three years after the Hinckley verdict, two-thirds of the states placed the burden on the defense to prove insanity, while eight states adopted a separate verdict of "guilty but mentally ill," and one state (Utah) abolished the defense altogether.

In addition to shifting the burden in insanity cases, Congress also narrowed the defense itself. Legislation passed in 1984 required the defendant to prove a "severe" mental disease and eliminated the "volitional" or "control" aspect of the insanity defense. After 1984, a federal defendant has had to prove that the "severe" mental disease made him "unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts."

HINCKLEY AT ST. ELIZABETHS

Following his acquittal, John Hinckley was transferred to St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington. Under the law, he was entitled to regain his freedom once it was established that he was no longer a threat, because of his mental illness, to himself or others.

On December 17, 2003, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley was entitled to unsupervised visits with his parents. In 2007, a request for unsupervised visits extending as long as one month was denied. The judge based his denial not on any problems with prior visits (there were none), but because the hospital had not taken "the necessary steps" for such a "transition." In July 2016, Judge Paul Friedman concluded that John Hinckley no longer posed a serious risk to himself or others and ordered his release. On September 10, 2016 Judge Friedman established the conditions for his release: limiting his residence and travels to southern Virginia, forbidding contact with past or present presidents (or their relatives, homes, or graves), banning contact with Jodie Foster or other entertainers, and prohibiting the watching of violent movies, television, or online digital materials. In 2018, a restriction that confined Hinckley's residence to his mother's house ended. He could live anywhere he wanted, with his doctors' approvals.

On September 27, 2021, John Hinckley, age 66, was approved for unconditional release by U. S. District Judge Paul Friedman. Judge Friedman noted that "very few patients at St. Elizabeths Hospital have been studied more thoroughly than John Hinckley." Hinckley's attorney, Barry Levine, said his client has followed the rules and the law for years and that his "mental disease is in full, stable and complete remission and has been so for over three decades." Hinckley will be given his unconditional release in June of 2022, provided he continues to comply with his release requirements and no new concerns about the risks he might pose to others develop in the interim period, under a settlement agreed to by the Justice Department. Hinckley is currently living on his own, but is being monitored by the government.