Humans and Animals: A Brief History of Our Complicated Relationship

by Douglas O. Linder (2021)

Humans and Animals in Prehistorical Times

The earliest humans began interacting with other animals they began walking the African savannah over two million years ago. It’s been a long and complicated relationship ever since.

Most people imagine cavemen as hunters, wielding large clubs as they roamed around ancient grasslands, while cavewomen busied themselves gathering berries and other fruits—work that supplied about 70% of the dietary calories. In fact, the earliest cavemen likely did more scavenging than hunting, according to archaeological evidence.

At a site near the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya, archaeologists discovered stone tools and the cracked skulls of large antelopes, similar in size to wildebeests. The skulls were almost certainly scavenged by ancient humans two million years ago. Animal scavengers like hyenas consume almost all of a carcass, but leave the heads because they lack the ability to crack open the skulls to extract the brains. Nomadic humans, however, mastered that trick. They opened the discarded animal heads to gobbled up the fatty, nutritious, energy-rich brains. In addition, animals’ bone marrow, also fatty and energy rich, was likely an important food source for scavengers. Researchers theorize that these additions to the diet fueled the evolution of modern humans. Without animals, we wouldn’t be who we are.

Cave painting depicting bison dating to about 18,000 BCE (Altamira Cave, Spain)

DOMESTICATIONS

Humans have domesticated animals for several purposes, including for food (meat and milk), work, transportation, pest control, and companionship. The earliest domestications can be traced to a period of history when humans began transitioning from relying primarily on food gathered in the wild (the hunter-gatherer economy) to a farming economy. It was obviously a huge benefit to have food on hand when hunting was unproductive.

Among the first animals domesticated for use as a food source were sheep, whose domestication occurred between 12,000 and 9,000 B.C. in Southwest Asia. (Domestication is not a single event, but generally occurs at different times and in different places.) Goat domestication began somewhat later, probably about 8,000 B.C. Dates for domestication were determined largely through studies of genetic mutations that caused humans in certain regions became lactose-tolerant, a mutation that bestowed a large advantage on a population that could use sheep or goats as milk sources.

Pigs and cattle were also domesticated around 12,000 to 8,000 B.C. The first domestication of pigs seems to have been in Mesopotamia, while cattle domestication came a few thousand years later, in the region between modern-day Turkey and Pakistan. Generally, pig and cattle domestication occurred in communities that were more settled than those areas where sheep and goat domestication first occurring. Pig and cattle domestication allowed the feeding of larger populations and contributed to growing population density.

The origins of horse domestication is hard to pinpoint because wild horse populations were dispersed across many regions and domestication of the species did not produce the distinct morphological changes observed in other animals. “(Compare, for example, the domestication of dogs from wolves. Scientists can easily distinguish the skeletal elements between wolves and dogs because wolf heads grow larger through adulthood, whereas that of a dog retains juvenile traits.) Horse domestication seems to date back to about 5,000 B.C. in Kazakhstan and 4,000 B.C. in the Eurasian Steppes region, stretching from Hungary to Mongolia. The first domesticated horses were likely used for food, not transportation. The first evidence of horse riding dates to roughly 3,500 B.C., based on evidence of bit-worn teeth in fossils. By 2,000 B.C. horses were being employed to draw chariots in Mesopotamia.

Domestication of dogs can be traced back, thanks to a dog jawbone found in Iraq, at least 12,000 years. Cat domestication, from five different types of wildcats began about 5,500 B.C. with the first evidence of a domesticated cat being found in Cyprus. It is likely cat domestication was encouraged by a desire for their use in controlling mice and rat infestations around human settlements.

Fossilized chicken bones dating back to about 5000 B.C. have been found in northeastern China, even though their wild ancestors came from the jungles of tropical Asia. Most scholars believe that the original purpose of domestication of chickens was for cockfighting, not egg production.

Other species, while never being fully domesticated, have been employed to serve human purposes. For example, there is evidence of elephants being used for heavy work in India as early as 2,000 B.C. They might have used in the South Asia region for thousands of years earlier than that.

Humans and Animals in Ancient Times

MORAL/LEGAL STATUS OF ANIMALS

The Old Testament was compiled/written by Jewish priests in the 6th century BCE. Unsurprisingly, the Old Testament puts humans at the top of the natural world. In the Book of Genesis 1:26, Adam is given "dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth." At the same time, however, the Old Testament cautions against treating animals as things; they are beings whose interests deserve respect. For example, the Third Commandment (Exodus 20) not only says man should observe the Sabbath and rest, it says the same for mans’ work animals: “Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your male or female servant, nor your animals, nor any foreigner residing in your towns.” The Bible also forbids “plowing with an ox and an ass together” (Deut. 22:10–11). (Why you ask? Because an ass would be hard-put to keep up with the far more powerful ox.) The Bible similarly forbids “muzzling an ox when it treads out the grain” (Deut. 25:4–5). Animals, in the Old Testament, are not seen as mere things, but rather as beings with lives and feelings.

"Don't do this!" according to Exodus: plowing with an ox and ass yoked together

Exodus also addresses the matter of animal liability for harms they might cause. Whether the animal could be subject to punishment could turn on the mental states, of the animal or owner, or both. It could matter whether an animal committed a deliberate or accidental harm, or whether the animal was provoked or whether it acted in self-defense (for example, in response to an attack by other animals). The owner’s mental state could also be important. Exodus says that if an ox gored, the ox could be put to death, the owner should generally be spared punishment, but not if the owner was aware of the propensity of the animal to gore. Owners could be liable for not keeping known dangerous animals under control.

In Ancient Greece, Aristotle had a lot to say about animals. He declared that animals lacked reason (logos), reasoning (logismos), thought (dianoia), and belief (doxa). He agreed with Old Testament authors that animals rightfully ranked far below humans in the Great Chain of Being. Aristotle’s writings, specifically his History of Animals, nonetheless show he respected animals. He wrote, “In a number of animals we observe gentleness or fierceness, mildness or cross temper, courage or timidity, fear or confidence, high spirit or low cunning, and, with regard to intelligence, something equivalent to sagacity. Some of these qualities in man, as compared with the corresponding qualities in animals, differ only quantitatively: that is to say, a man has more or less of this quality, and an animal more or less of some other; other qualities in men are represented by analogous and not identical qualities; for instance, just as in man we find knowledge, wisdom, and sagacity, so in certain animals there exists some other natural potentiality akin to these.”

Aristotle

Other philosophers weighed in as well. Interestingly, Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BCE), one of Aristotle's pupils, argued that animals did have reasoning (logismos) and opposed eating meat on the grounds that it stole their lives and was unjust. The philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras argued for giving animals respect and treating them with dignity. Pythagoras believed that human and nonhuman souls were reincarnated from human to animal, and vice versa. Plutarch, in his Life of Cato the Elder, noted that law and justice are applicable only to humans. But he argued that beneficence and charity towards beasts is characteristic of a gentle heart. The most comprehensive treatment in the Ancient World of man’s proper relationship to animals comes from the Neoplatonist philosopher Porphyry (234–c. 305 CE), in his On Abstinence from Animal Food, and On Abstinence from Killing Animals.

Emperor Ashoka the Great

In the Ancient Eastern World, animals got even more respect. Concern for the welfare of other animals arose as a system of thought in the Indus Valley Civilization. With the religious belief that ancestors return in animal form, it follows that animals should be treated with the respect due to a human. Buddha taught that it is a sin to kill any living being, contending that civilization depends on the “spirit of Maitri,” a friendliness toward all living things. Both Hindu and Buddhist societies embraced vegetarianism beginning in the third century BCE, though Hinduism allowed limited animal sacrifice in religious ceremonies. Several kings in India built hospitals for animals. The emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE) banned hunting and animal slaughter. Jainism took respect for animals to its extreme. Jains believed that humans should do whatever they could to avoid harming any living creature, even to the point of sweeping paths in front of them to prevent injury to any insect life. In general, Eastern philosophies continue to this day to see animals and humans as part of a larger one and equal in moral worth, in contrast to the greater willingness of Western philosophies to see man as separate and superior.

Jared Diamond noted that animals in ancient times represented a larger fraction of social wealth than they do today, and were “crucial to those human societies possessing them.” Both Biblical and Roman law recognized their importance. Roman law allowed wild animals to be reduced to private ownership by capture.

Illustration for Aesop's fable "The Crow and the Pitcher"

The best known stories about animals from the classical world are attributed to Aesop, a slave and storyteller believed to have lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. The collection of stories often called “Aesop’s Fables” belonged to the oral tradition and were not collected and put into written form until at least three centuries after Aesop’s death. The fables featured talking animals or insects discovering moral lessons about life. A couple of the more famous of Aesop's stories include "The Hare and the Tortoise" and "The Crow and the Pitcher."

ANIMALS USE FOR ENTERTAINMENT

Exotic animals fascinated the ancients. As early as 2000 BCE, lions were kept and displayed in cages in Macedonia, according to archaeological evidence. Wild animals, including elephants, bears, tigers, and giraffes were collected by rulers from Egypt to Babylonia, to Assyria, to Rome, and to China.

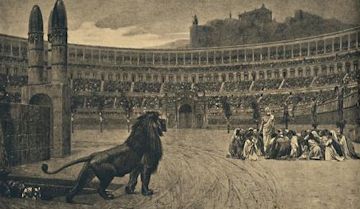

The Roman Empire is well-known for its use of animals for entertainment. Emperors held gory spectacles in circular arenas in which animals fought to the death, either with each other animals or with human gladiators. Perhaps the most famous large venue for this type of entertainment was the Circus Maximus in Rome.

"Last Prayer of the Christians" at Circus Maximus in Rome

In contrast to the Romans, the Greek tended to take a more scientific interest in animals, and were among the first to collect wild animals for study.

HUNTING

Hunting in the Ancient World was pursued both for sport and as a way for demonstrating abilities as warriors and proving courage. Art on the walls and temples of Assyrians and Babylonians often depicted members of the elite in chase. For example, Ashurbanipal, the Hunting King, in the 7th century BCE is immortalized in a bas-relief with the boast: “I killed the lion.” Sāsānian king Kavadh I is depicted on a 5th century silver dish in full chase after wild ram.

Silver plate from 5th century depicting King Kavadh chasing a ram (Metropolitian Museum of Art)

For many societies in ancient times, hunting was a privilege for the privileged classes, those with leisure time and wealth. In ancient Egypt, hunters constituted a distinct social class; they hunted on their own as well as served the needs of hunting noblemen. In the Nile valley, animals were sometimes driven into enclosed preserves for sport hunting that might include gazelle, oryx, wild ox, Barbary sheep, and other species. The Bible also includes references to hunting that suggest game was prized and sought after by Israelites.

Xenophon makes reference to hunting in Greece in the 4th century BCE. He describes his own experience hunting hare, and includes description of hunting of boar, stag, and other animals by horsemen using spears or by takings using pitfalls.

In Rome, hunting was less associated with privilege than in other ancient societies, and seems to have been mostly undertaken by hunting professionals and members of lower social classes.

ANIMAL HUSBANDRY

Ancient civilizations kept livestock, both for meat and dairy. In ancient Egypt, cattle was probably the most valuable livestock, but sheep, goats, pigs, and poultry were also kept. Added to this list, in ancient Rome, were domesticated ferrets (from polecats) which, according to Pliny the Elder, were used to flush rabbits from burrows (Romans were fond of rabbit).

ANIMAL TESTING

The use of animals for testing can be traced back to 4th and 3rd century BCE Greece. Both Aristotle and Erasistratus performed experiments on animals. A 2nd century Roman physician named Galen dissected pigs and goats earned the name the "Father of Vivisection."

Humans and Animals from 500 to 1600 A.D.

MORAL/LEGAL STATUS OF ANIMALS

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) published a book ten years before his death called Of God and His Creatures. In it, Aquinas argues that the behavior of animals was entirely driven by natural instincts, not be any reason or purposeful motivation. Animals, according to Aquinas, had no comprehension of the future and lived only in the present, and saw this as proof that animals lacked immortal souls, unlike humans.

Perhaps the religious figure most associated with animals during the medieval period was St Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), a Franciscan friar with a real soft spot for animals. Francis was said to preach to animals and, whenever he discovered a life animal in a trap, release it. (Legends abound about Francis, including one that holds he persuaded a wolf to stop terrorizing a village and eating the livestock.) Francis is considered the patron saint of animals and ecology.

St. Francis of Assisi

The Middle Ages was a period of myth and superstition—and animals were the subject of a good many of them. Cats got the worst of it. Several explanations have been offered for what, over the course of a couple of centuries was a wholesale slaughter of the cats of Europe. Cats probably aroused suspicion in part for their general unwillingness, unlike dogs, to take orders from humans. Then there were the loud and wild nighttime mating mutual of cats which might have brought to many a medieval mind thought of witchcraft. Finally, it seemed to some, that older (often single) women accused of witchcraft seemed disproportionately likely to have cats. Hmmmm. When, in the 13th century, a devil worshipping sect in southern France came to be linked to black cats which, it was believed, was the Devil in a cat’s body, it was enough to make cats the symbol of heresy and evil. Much of Europe, with the support of the Church, went on a cat-killing rampage, so severely depleting cat populations that by the early 14th century only a small number of feral cats survived in many areas. When the bubonic plague, or Black Death, swept across Europe beginning in 1347, it did not help that cat populations had dropped to the point that they were no longer a serious check on the infected rodents that spread the disease. The greatly decreased number of cats likely also contributed to the dramatic increase in food poisoning caused by rat droppings in the grain supply.

The persecution of cats continued, however, for centuries. Cat hatred was on display in the 16th century coronation of Queen Elizabeth I, when cats were burned alive as part of the celebration. It was not a good time to be a cat in Europe. (In Asia and the Middle East, residents had much more appreciation for the rodent-hunting skills of cats. And, even in Europe, there were exceptions. In 945 in Wales, for example, Hwyel the Good put in place protections for cats, understanding their role in protecting the region’s grain supplies.)

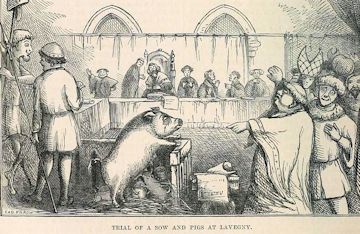

Animals on Trial

The Middle Ages was also a time in which animals were put on trial for their crimes. The command of Exodus 21:28, in this religious time, was no doubt part of the inspiration for the trials: "If an ox gore a man or a woman that they die, then the ox shall be surely stoned.” A book by E. P. Evans published in 1906 describes 191 animal trials in Europe (mostly in Germany, France, and Italy) from roughly 1400 to 1600. The collection includes animals put on trial for murder, fraud, and theft. Animals in most cases actually were appointed a lawyer and carried into court. The track record for animals in court was not good, with most found guilty and executed (often by hanging).

Swine faced murder charges most frequently, as could be expected at a time when pigs often bedded in the same space as peasants. But due process for the animals was expected, and when it wasn’t given, there were consequences. When the municipal executioner of Schweinfurt hanged a pig that had bitten off a child’s ear before a death warrant was issued, the executioner was forced to flee for his disrespect of process.

Although guilty verdicts were the norm, there were sometimes acquittals. The killing of a five-year-old boy in 1457 in Burgundy led to the prosecution of a sow and six piglets, all found covered with blood and next to the boy’s body. The sow was convicted and hanged after the court heard from eight witnesses, but the piglets were ultimately acquitted on the ground that no evidence directly implicated them in the murder.

Justice in medieval times could be tough. A sow convicted in 1386 in Falaise for gnawing the face of a baby was ordered not only executed, but tortured. A mural was painted in the village church to depict the scene. It showed a thrashing pig on the gallows dressed in human clothes,

It was not only mammals that faced their days in court. In 1545, in the Alpine village of St. Julien, weevils were put on trial for ravaging the area’s vineyards. Two lawyers were appointed to defend the insects. One lawyer for the weevils argued, it would be “unbecoming to proceed with rashness and precipitation against the animals now actually accused and indicted.” Better, he said, to turn to the Lord and carry communion wafers around the affected vineyards. The defense counsel’s plan was adopted, and his plan seemed to work—at least for a couple of years. Also, the lamprey in Lake Geneva, accused of molesting local salmon, were ordered to cease and desist their molestation by a court in 1451. A rooster in Basel in 1474 that performed the “unnatural” act of laying an egg was ordered executed.

Not everyone, of course, agreed that trials of animals made sense. Thomas Aquinas argued that trials were proper only for “rational” beings, and he didn’t consider animals to be included in that category. Aquinas’s contemporary, lawyer Philippe de Beaumanoir, wrote “punishment is lost on animals.”

ANIMAL ENTERTAINMENT

The Middle Ages were a violent time and many of the period liked their entertainment violent as well. So it should come as no surprise that much of the animal entertainment featured violence. Cockfights and dogfights were popular. Bullbaiting and bearbaiting was prevalent.

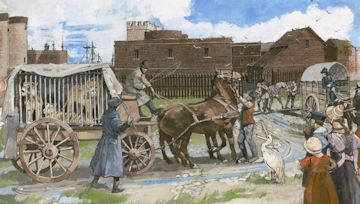

The Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London

But Europeans of the time also enjoyed viewing exotic species and exhibits of wild animals called menageries were popular. The menageries used cages or small pits to protect people from the animals, while still allow easy viewing. In Britain, the royal menagerie was housed at the Tower of London and remained there for centuries. The royal collection (first established by King Henry I in the 12th century) included both animals captured in the wild by British subjects and others given as gifts to the Crown by the leaders of other countries.

HUNTING

Laws were enacted that regulated hunting on royal territory. Poaching, which had been generally tolerated in earlier times, became severely punished. Non-nobles were formally prohibited from hunting certain species.

Hunting was a big deal for royalty. Under the reign of Francis I in the 1500s in France, hunting with hounds became a lifestyle choice. Spectacular post-hunt banquets were opportunities to grease social relationships in court.

Beginning in the 13th century, works about wild animals, prey typology and hunting techniques were popular—and so were recipes for preparing meat in royal banquets.

In addition, hunting was widely practiced as a means of dealing with a proliferation of animals damaging to crops and threatening to livestock. Under orders of King Edgar and King Canute in the 10th and 11th centuries, wolf populations were hunted to near the point of extinction in England.

Laws and social practices made a sharp distinction between hunting for sport and hunting for food. A strict code of behavior developed for hunting for sport. A gentleman taking game birds for recreation was expected to use a falcon, while a fowler who earned a living by selling birds at market could use nets. A fairly complex European canon of “fair play” developed for hunters. The code demanded that those hunting wild creatures for their entertainment give the quarry a fair chance to escape and to avoid unnecessary suffering of wounded game. A hunter who wounded an animal was expected to track it down and kill it. Shooting a sitting duck was bad sport, as was waiting for a kill by a water hole or a block of salt.

Humans and Animals, from 1600 to 1800

MORAL/LEGAL STATUS OF ANIMALS

One of the earliest animal protection laws in Europe was enacted in Ireland in 1635. The law prohibited both pulling wool off sheep and the attaching of ploughs to horses' tails, describing both practices as a form of "cruelty used to beasts." In America, the first known animal protection law was enacted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The law declared: "No man shall exercise any Tirrany or Crueltie toward any brute Creature which are usually kept for man's use."

In the 1700s, numerous laws weree enacted in England forbidding cruelty to animals. The laws contained many loopholes and forbid actions toward animals that are sadistic, gratuitous, or blatantly cruel. This trend is likely the result of a rising urban middle class that had grown disgusted with the casual cruelty of the lower class, which is largely rural, toward animals—and perhaps also displeased with the sometimes cruel hunting practices of the aristocratic class.

During the 1600s, the prevailing philosophical view of animals was that they were mere mechanistic creatures. According to René Descartes, “[Animals] eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.” Later, in the 1700s, philosophers such as Voltaire would challenge this view of animals: “Hold then the same view of the dog which has lost his master, which has sought him in all the thoroughfares with cries of sorrow, which comes into the house troubled and restless, goes downstairs, goes upstairs; goes from room to room, finds at last in his study the master he loves, and betokens his gladness by soft whimpers, frisks, and caresses.” Voltaire noted that if you dissect a dog “you discover in him all the same organs of feeling as in yourself. Answer me, mechanist, has Nature arranged all the springs of feeling in this animal to the end that he might not feel?”

John Locke contended that animals did have feelings, and that unnecessary cruelty toward them was morally wrong. He saw animal cruelty had having negative effects on those who engaged in it: "For the custom of tormenting and killing of beasts will, by degrees, harden their minds even towards men." Immanuel Kant took a similar position. In 1785, he wrote, "Cruelty to animals is contrary to man's duty to himself, because it deadens in him the feeling of sympathy for their sufferings, and thus a natural tendency that is very useful to morality in relation to other human beings is weakened."

Romantic philosopher believed that natural law protections extended to animals. In his Discourse on Inequality (1754), he wrote: "By this method also we put an end to the time-honored disputes concerning the participation of animals in natural law: for it is clear that, being destitute of intelligence and liberty, they cannot recognize that law; as they partake, however, in some measure of our nature, in consequence of the sensibility with which they are endowed, they ought to partake of natural right; so that mankind is subjected to a kind of obligation even toward the brutes. It appears, in fact, that if I am bound to do no injury to my fellow-creatures, this is less because they are rational than because they are sentient beings: and this quality, being common both to men and beasts, ought to entitle the latter at least to the privilege of not being wantonly ill-treated by the former."

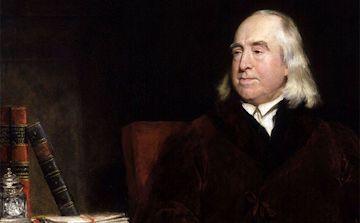

Jeremy Bentham

Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, while not arguing that humans and nonhumans had equal moral significance, suggested that the interests of animals should at least be taken into account in a utilitarian calculus. Bentham noted, “A full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?”

Humans and Animals in the 19th Century

LEGAL/MORAL STATUS OF ANIMALS

In the early 1800s, debated erupted in Britain concerning proposed animal protection legislation. A bill introduced in 1800 against bull baiting was opposed be some MPs on the grounds that it was anti-working class and was defeated by two votes. In 1809, a bill was introduced to protect cattle and horses from malicious wounding, wanton cruelty, and beating. The author of the legislation told the House of Lords that animals should not be treated as mere property: "The animals themselves are without protection--the law regards them not substantively--they have no rights. The Bill was passed by the Lords, but defeated in the House of Commons. In 1822, the first successful effort was made in Parliament to enact animal protection legislation with the passage of the "Ill Treatment of Horses and Cattle Bill.” The Act made it illegal, punishable by fines up to five pounds or two months imprisonment, to "beat, abuse, or ill-treat any horse, mare, gelding, mule, ass, ox, cow, heifer, steer, sheep or other cattle." Other nations in Europe followed suit in the next few decades. In the United States, a New York court found that wanton cruelty to animals was a misdemeanor at common law.

In England, a series of amendments extended the reach of the 1822 Act, which became the Cruelty to Animals Act. In 1835, the law was amended to ban cockfighting, baiting, and dog fighting.

Concern for animal welfare led to the creation of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824 in England. The Society published letters and articles promoting kindness toward animal and sought to use its influence to promote social reforms. The Society became the Royal Society in 1840, when it was granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria, whof strongly opposed to vivisection.

Numerous writers and thinkers published their thoughts about animal welfare and animal rights, including Edward Payson Evans (1831–1917), John Muir (1838–1914), and J. Howard Moore (1862–1916). Arthur Schopenhauer argued in 1839 that the view of cruelty as wrong only because it hardens humans was "revolting and abominable." Schopenhauer wrote people were "awakening more and more to a sense that beasts have rights, in proportion as the strange notion is being gradually overcome and outgrown, that the animal kingdom came into existence solely for the benefit and pleasure of man." He applauded animal protection legislation in England: “To the honor, then, of the English, be it said that they are the first people who have, in downright earnest, extended the protecting arm of the law to animals."

Vegetarianism began to win advocates. The poet Percy Shelley wrote two essays advocating a vegetarian diet, both for ethical and health reasons.

Philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) argued that utilitarianism should take the welfare of animals into account: "Nothing is more natural to human beings, nor, up to a certain point in cultivation, more universal, than to estimate the pleasures and pains of others as deserving of regard exactly in proportion to their likeness to ourselves. ... Granted that any practice causes more pain to animals than it gives pleasure to man; is that practice moral or immoral? And if, exactly in proportion as human beings raise their heads out of the slough of selfishness, they do not with one voice answer 'immoral,' let the morality of the principle of utility be forever condemned."

Charles Darwin, in his On the Origin of Species (1859) argued that humans and animals are kin and that animals have social, mental and moral lives too. He wrote in his The Descent of Man (1871) that "There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties." Animals, Darwin said, could reason, make decisions, hold memories, had the power of imagination, and emotional lives. To Darwin, "humanity to the lower animals" was one of the "noblest virtues with which man is endowed." Darwin testified before a Royal Commission on Vivisection, lobbying for a bill to protect both the animals used in vivisection, and the study of physiology.

In the United States, the first animal protection group founded was the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), in 1866.

In the late 1890s, even while interest in animal protection grew, scientists increasingly embraced the idea that the attribution of human qualities to nonhumans was unscientific.

Humans and Animals: 1900 to Present

MORAL/LEGAL STATUS OF ANIMALS

The notion that animals should be seen only as physiological entities was pushed by Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov wrote in 1927 that animals should be studied "without any need to resort to fantastic speculations as to the existence of any possible subjective states."

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) argued in 1931 that vegetarianism should be pursued in the interests of animals--and not just as a human health issue.

In April 1933, the German Nazi Party enacted laws regulating the slaughter of animals, including kosher slaughter, practiced by Jews. Later that year, Adolf Hitler introduced an animal protection law with the promise: announcing an end to animal cruelty: "Im neuen Reich darf es keine Tierquälerei mehr geben." ("In the new Reich, no more animal cruelty will be allowed.") Even the worst mass murderer of the 20th century had a soft spot for animals. In 1934, the Nazis prohibited hunting and in 1937-38 enacted laws regulating animal transport in cars and trains. Hitler was a vegetarian in the later years of his life.

After World War II, the use of animals in research increased. By 2000, about 50 to 100 million animals were being used for testing annually. The number of animals killed for food also increased dramatically, rising into the billions annually in the late 20th century, with both increased population and affluence.

In 1973, The New York Review of Books commissioned Australian philosopher Peter Singer to write a book on what he had called "the last remaining form of discrimination," discrimination by man against other species. Singer’s book, Animal Liberation, was published in 1975 and is considered one of the movement’s canonical texts. Singer based his argument on utilitarianism. He argued in favor of the equal consideration of human and animal interests. He took the position that there is no reason to assume that an action that causes suffering to animals should count for less than one that causes an equal amount of suffering to humans. Suffering is suffering; pain is pain. Singer used the term "speciesism" to describe the favoritism we show human beings over other animals. The book's publication triggered a groundswell of scholarly interest in animal rights.

In 1984, philosopher Tom Regan published his The Case for Animal Rights. In his book, Regan argues that nonhuman animals are "subjects-of-a-life" and possess moral rights.

The 1970s saw the beginning of radical and militant action on behalf of animal welfare. In 1973, members of the Animal Liberation Front set fire to a pharmaceuticals research laboratory in England that used animals for testing purposes. Despite viewing arson as an appropriate tool in its fight, the group described itself as a "nonviolent guerilla organization dedicated to the liberation of animals from all forms of cruelty and persecution at the hands of mankind." In 2005, the US Department of Homeland included the Animal Liberation Front on a list of domestic terrorist organizations.

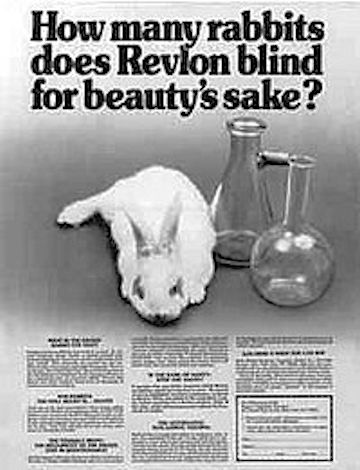

Henry Spira, founder of Animal Rights International in 1974, and introduced the idea of "reintegrative shaming.” This approach attempts to draw public attention and shame to corporations and individuals they see as abusing animals, such as cosmetic companies using animals for testing or individuals wearing fur. This approach has been adopted and employed by groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. One Spira campaign was aimed at the cosmetics company Revlon. He placed full-page ads in newspapers featuring a rabbit with sticking plaster over the eyes, and the caption, "How many rabbits does Revlon blind for beauty's sake?" Revlon ended its animal testing program.

Some nations have now completely banned the use of certain animals in testing. In 1999, New Zealand passed a new Animal Welfare Act that effectively prohibited experiments using "non-human hominids." In 2005, the Austrian parliament banned experiments on apes, unless they are performed in the interests of the individual ape. Some nations have also banned the use of animals in circuses, including Bolivia, Singapore, and several Scandinavian countries. In 2010, Catalonia enacted a law banning bull fighting, the first such ban in Spain. In 2014, Palitana City in Indian state of Gujarat (a destination for Jain pilgrims) became the first city in the world to be legally vegetarian. The city prohibited the sale of meat, fish and eggs.

Palitana City, India, the world's first vegetarian city

In the United States, legal efforts to assert that certain animals are persons for legal purposes began in 2011, when People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals sued SeaWorld over the captivity of five orcas in San Diego and Orlando, arguing that the whales were being treated as slaves in violation of the 13th Amendment of the Constitution. The federal courts refused to buy the argument.

In 2007, Law professor Steven Wise founded the Nonhuman Rights Project, an organization dedicated to securing “fundamental rights for nonhuman animals through litigation, legislation, and education.” In 2013, NhRP brought its first case, seeking a common law writ of habeas corpus for a chimpanzee held in a cage in upstate New York.

Today, the world is living through a pandemic brought on by our failures to fully appreciate, and guard against, risks associated with human-animal interactions, whether the actual source of the zoonotic virus proves to be live animal markets, wildlife trade, or meat packaging. Will this pandemic, or the one that follows, finally lead end to change in our heavily animal-based diet? A hundred years from now, how many Palitanas will there be?