Al Capone, head of the most profitable crime syndicate of the Prohibition Era and mastermind of the notorious 1929 "Valentine's Day Massacre," seemed above the law. In the end, however, Capone would be brought to justice not for murder, extortion, or bootlegging, but for failing to pay his income tax. Credit for his conviction is due less to Elliot Ness and The Untouchables than to the dogged work of Bureau of Revenue investigator Frank Wilson and a clever surprise pulled by a federal judge, James Wilkerson. Al Capone once complained about the bad reputation of his criminal enterprise: "Some call it bootlegging. Some call it racketeering. I call it a business." The lesson of The People vs. Al Capone is that a profitable businessman, no matter how he earns his income, does have to pay his taxes.

Twenty-year-old Al Capone arrived in Chicago in 1919 to help run Johnny Torrio's bootlegging operation. It was Capone's job to keep the competition in line, and he did so with ruthless efficiency. When Torrio left Chicago in 1925, driven out by maiming and death threats, Capone took over the bootlegging operation. Operating from his headquarters at the Hawthorne Inn in Cicero (with its bulletproof shutters on every window), Capone dispatched his enforcers. On April 27, 1925, a five-car motorcade carrying Capone's trigger men swept by members of a rival bootlegging gang as they left a bar and opened fire with machine guns. One of the men killed, it turned out, was not a known bootlegger but rather Bill McSwiggin, an assistant state's attorney. Chicagoans were used to reports of gang members killing other gang members, but the murder of a top law enforcement officer was something new--and the public looked for a response to the growing violence in their city. Authorities charged Capone with the McSwiggin murder, but the fix was in and, six grand juries and no indictments later, charges were dropped.

By 1926, while still maintaining offices in Cicero, Capone had moved his headquarters to fifty rooms of Chicago's Hotel Metropole. With the city's new mayor, Big Bill Thompson, in his pocket, Capone carried out his illegal bootlegging, racketeering, and gambling businesses with virtual impunity. His enforcers carried officially stamped cards issued by the city that read: "To the Police Department--you will extend the courtesies of this department to the bearer."

When Chicago's winters were to much to bear, Capone headed south to his luxurious Miami estate, surrounded by a ten-foot concrete wall, where he could direct operations poolside or from his thirty-two foot cabin cruiser. By 1928, Capone's syndicate was grossing an estimated $105,000,000 a year. Capone liked to think of himself not as a ruthless criminal, but as "a public benefactor." "I've given people light pleasures," he said, "shown them a good time."

Capone chose to view the killing of rival gang members as a necessary evil: "killing a man in defense of your business" is like "the law of self-defense,...a little broader than the law books look at it." And could he kill. On May 7, 1928, Capone held a banquet to which he invited three former associates, men he knew had joined in a plot to assassinate him, but men who still thought they were on good terms with Capone. Drunk and full, the three men suddenly found themselves surrounded by Capone's men who tied each to a chair. Capone pulled out a baseball bat and with shocking deliberation beat each man to death. The best known of the Capone-ordered killings came on Valentine's Day 1929. While seven member of George "Bugs" Moran's bootlegging gang waited in a Chicago warehouse, expecting the arrival of a truckload of whiskey, a Cadillac carrying six of Capone's men, four dressed in police uniforms, pulled up in front of the warehouse. The members of the Moran gang fell amidst a hail of bullets from machine guns, bodies strewn against a yellow brick wall. Few doubted who the killers were. "Only Capone kills like that," Moran said.

The Treasury Department Launches an Investigation

Capone in 1929 might have been worth about $30 million, but no income tax return had ever been filed in his name. Two years earlier, in United States v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court had ruled that the Fifth Amendment's privilege against self-incrimination did not protect Manley Sullivan, a bootlegger convicted of failing to file a return showing the profits from his illegal businesses. With the Sullivan case in mind, President Herbert Hoover instructed Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, " I want that man Capone in jail." Secretary Mellon summoned Elmer Irey, head of Treasury's Special Intelligence Unit, and told him his office was charged with the responsibility of putting Capone behind bars. For the day-to-day job of gathering incriminating evidence for Capone's tax evasion case, Irey turned to Frank Wilson, his most aggressive and relentless investigator.

Frank Wilson and his team of five other Treasury investigators set up offices in the Chicago Post Office Building and set about the job of building a case against Capone. Capone made their task difficult by not maintaining a bank account and never signing any checks or receipts. An extravagant lifestyle could be evidence of substantial unreported income, so investigators examined department store, jewelry store, car dealership, and hotel records for evidence of Capone’s expenditures. They uncovered purchases of high-end furniture, custom-made shirts, diamond-studded belt buckles, gold-plated dinner service, hotel suites, and a Lincoln limousine. They tracked down telephone bills totaling $39,000 and evidence that he paid thousands to host a luxurious party on the night of the Dempsey-Tunney heavyweight fight. While such unusual extravagance does not in itself prove taxable income, a juror could easily draw such an inference.

While successful in tracking down evidence of expenses, investigators encountered considerable difficulty in finding direct evidence of income. As Frank Wilson recalled years later, “I prowled the crummy streets of Cicero, where a twitch of Al’s little finger had the force of an edict, but there was no clue that a dollar from the big gambling places, the horse parlors, the brothels, or the bootleg joints ever reached his coffers." Potential witnesses, when subpoenaed, rarely cooperated. Wilson described most as either "hostile to government and ready to give perjured testimony" or "so full of fear of the Capone organization...that they evaded, lied, or left town."

To convict Capone would require help from inside Capone's illicit operation, but--for reasons all too obvious--few on the inside wanted to step forward to help the government make its case. One who did was Eddie O'Hare, owner of the patent for the mechanical rabbit used in greyhound racing. O'Hare ran dog racing tracks for the Capone syndicate in the Chicago area, as well as in Florida and Massachusetts. (Years later, just days before Capone's release from prison, O'Hare would pay the ultimate price for the leads he provided the government over the course of their two-year investigation. While driving on a Chicago street, he was gunned down by two men in a passing car. His son, Edward O'Hare, was the first naval aviator to win the Congressional Medal of Honor. In 1949, Chicago's new international airport was named in Edward's memory.)

The first big break in the investigation came in the summer of 1930 when Wilson stumbled across three bound ledgers seized in a 1926 raid of one of Capone's establishments. The ledger was divided into columns with labels such as "Craps," "21," and "Roulette." Every few pages totals were entered and then divided into smaller amounts among "Town," "Ralph," "Pete," and "A." With the ledger also including a few references to "Al" it wasn't much of a leap to conclude that the ledger recorded the monthly income from a gambling hall that went to Capone and his associates. Building on the ledger evidence, Wilson collected sworn testimony from persons whose participation in a citizen's raid on a Cicero gambling hall had left them convinced beyond any doubt that Capone was the proprietor of the place.

An even more significant potential witness was located by comparing the handwriting in the ledger with that on deposit slips from local banks. Investigators identified the likely author of the ledger as Leslie Shumway, the same man who signed deposit slips that turned up at a small Cicero bank. Agents tracked Shumway to Florida, where they interrupted a breakfast at his home to offer him a ride down to the Miami Federal Building to talk to agents. Threatened with a not-so-secret subpoena and well aware of what Capone might do to someone about to disclose embarrassing facts to the government, Shumway agreed to talk. In his affidavit, Shumway described the nature of the gambling businesses and stated that "I took orders relating to the business [from] Mr. Alphonse Capone." Almost immediately after Shumway put his signature on the affidavit, agents took him off to California, where they hoped he could be safely hid until trial.

In April 1930, Capone's tax attorney, Lawrence Mattingly, contacted Treasury and expressed the desire to have his client meet with agents to settle his indebtedness with the government. At the Federal Building in Chicago, Wilson and other agents interviewed Capone. In response to the question, "How long, Mr. Capone, have you enjoyed a large income?", Capone replied, "I never had much of an income." At the end of the interview, Capone grew testy. As he prepared to leave the room after the interview, he inquired, "How's your wife, Wilson?" If there was doubt as to whether that was a question or a threat, the doubt was resolved when Capone added, "You be sure to take care of yourself."

On September 30, Mattingly met with Wilson to discuss Capone's tax liability. He took a letter from his coat pocket and threw it over to the agent, saying, “This is the best we can do. Mr. Capone is willing to pay the tax on these figures.” The so-called "Mattingly letter" conceded taxable income for the six disputed years ranging from $26,000 in 1924 to $100,000 in 1928 and 1929. Wilson filed the letter away. A year later, the letter became the trial's most contentious piece of evidence.

Wilson, not a person easily intimidated, continued to identify witnesses and amass incriminating evidence. One of the last and most important witnesses to be discovered was Fred Reis, the named payee on numerous large cashier checks that Treasury assumed found their way into Capone's coffers. Reis decided to talk after having four solitary days to think about it in a cockroach-infested jail in Danville, Illinois. He admitted, first to agents and then in testimony before a Chicago grand jury, that his boss was Capone, and that the checks represented Capone's net profits at his Cicero gambling hall.

With Reis's statement, prosecutors decided they had enough evidence to go before a grand jury. (After completing his grand jury testimony, Reis was shipped off to South America for safekeeping until trial.) On March 13, two days before the statute of limitations would have run, the grand jury indicted Al Capone for evading federal income taxes in 1924. Two months later, the grand jury added counts for the years 1925 to 1929.

Over the three months that followed, Capone's attorneys met frequently with U. S. Attorney George E. Q. Johnson to discuss a possible plea bargain. With witnesses to try to keep alive and with thorny legal questions concerning the charges, Johnson was willing to listen, hoping to get a two-and-a-half year sentence out of the negotiations. With an agreement for the two-and-a-half year sentence apparently in place, Al Capone appeared on June 18, 1931 before Federal Judge James H. Wilkerson and entered a plea of guilty. Wilkerson adjourned court until July 30 to consider the plea.

On the day before his expected sentencing, Capone told reporters, "I've been made an issue and I'm not complaining, but why don't they go after all those bankers who took the savings of thousands of poor people and lost them in bank failures?" The next day, Judge Wilkerson surprised nearly everyone. Addressing Capone in his pea-green suit, Wilkerson announced, "The parties to a criminal case may not stipulate as to the judgment to be entered." There would be no plea bargain. There would be a trial. Wilkerson continued: "It is time for somebody to impress upon the defendant that it is utterly impossible to bargain with a Federal Court."

The Trial

About two weeks before the scheduled start of the Capone trial, informant Eddie O'Hare notified Wilson that Capone's organization had a complete list of prospective jurors and was already "passing out $1,000 bills," promising political jobs, giving away tickets to prize fights, and "using muscle too." Skeptical of O'Hare's claim at first, Wilson quickly came around when O'Hare produced the names and addresses of ten jurors, names 30 to 39 on the jury list. Concerned that thousands of hours of work was about to go down the drain because of a fixed jury, Wilson and U. S. Attorney Johnson related O'Hare's story to Judge Wilkerson in his chambers. Wilkerson told the men that he hadn't yet received his jury list for the Capone trial, but when he did he would call them. When the names on Wilkerson's list turned out to match exactly with the names on O'Hare's list, the judge met once again with Wilson and prosecutors. The judge seemed curiously unconcerned. "Bring your case into court as planned, gentlemen," he told the government's attorneys. "Leave the rest to me."

The Trial of Alphonse Capone opened on the morning of October 5, 1931 at the federal courthouse in downtown Chicago. Capone, accompanied by his bodyguard, smiled at jurors as he strolled into court in his mustard-colored suit. Judge Wilkerson took his seat at the bench and looked out over the packed courtroom. He called the bailiff to the bench. "Judge Edwards has another trial commencing today," he told the bailiff. "Go to his courtroom and bring me his entire panel of jurors; take my entire panel to Judge Edwards."

After a jury of twelve was seated, and after Assistant U. S. Attorney Dwight Green outlined the 23 charges of tax evasion against Capone in the government's opening statement, George Johnson called his first witness. Charles W. Arndt, a tax collector for the United States, told jurors that Al Capone failed to file any tax return at all during for the years 1924 through 1929.

The prosecution presented evidence that Capone owned gambling halls and derived substantial profits from those businesses. Chester Bragg testified that when he participated in the citizens' raid on the Hawthorne Smoke Shop, a gambling hall in Cicero, Capone arrived on the scene. As Bragg guarded the front door while other citizens carted out gambling machines and loaded them into trucks, Capone attempted to push his way in. Bragg testified that he asked Capone, "What the hell--do you think this is a party?" and that Capone answered, "I'm the owner of this place." Reverend Henry Hoover, leader of the Cicero raid, also testified. Hoover said that Capone complained to him during the raid, "Why are you fellows always picking on me?” and warned, "This is the last raid you'll ever pull." Leslie Shumway, the cashier at the Hawthorne Smoke Shop, presented the most damning evidence of the day. Shumway described the accounting procedures used at the gambling hall and estimated that the profits for the two years he worked there were over $550,000. When Shumway balked at positively identifying Capone as the owner of the establishment, prosecutors tried a different tack, asking questions whose answers seemed to assume Capone exercised control over the business. Jacob Grossman asked Shumway, "Did you any time after that have any conversation with Al Capone about carrying money over there?" The witness answered, "It was some time later that Al asked me what I would do if I got stuck up, and I told him, I says, 'I would just let them take it,' and he says, 'That is right.'”

On October 8, the courtroom erupted in heated debate when the prosecution sought to introduce the letter of Capone's tax lawyer, Lawrence Mattingly, which expressed his willingness to settle his client's tax liability for the years 1924 to 1929. Defense attorney Albert Fink argued, "A lawyer cannot confess for his client." Surely, Fink noted, Capone never meant to give Mattingly the "authority to make statements that may get him into the penitentiary." The controversy developed with Frank Wilson on the stand, describing the events in his office the previous fall when Mattingly first tossed the letter in his direction with the statement, “This is the best we can do. Mr. Capone is willing to pay the tax on these figures.” After argument on the letter's admissibility with the jury excused, Judge Wilkerson announced his decision: the letter would be admitted to show that the statement was made, but the contents of the letter could not be considered by the jury as proof of the statements made.

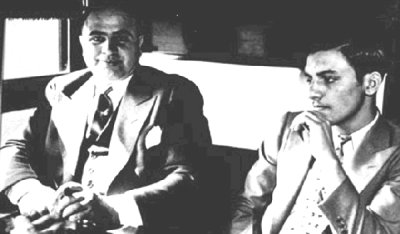

Al Capone (hands folded) in court with his attorneys

A series of prosecution witnesses presented evidence of Capone's lavish lifestyle. Parker Henderson testified that he sold Capone his Palm Island, Florida estate, with the title placed in his wife's name. "I asked Al if he was interested in buying any property and he said he was," Henderson told jurors. "So we made an appointment with him and carried him out and showed him several places. This place on Palm Island he seemed to like very much. Later he told me he had decided to take it. He gave me all money to put up the binder." Morrissey Smith, a clerk at Chicago's Metropole Hotel told jurors that Capone purchased the hotel's most expensive suites and hosted expensive parties. Asked in what denominations Capone would pay his bills, Smith replied, "Oh, hundred dollar bills, sometimes five hundred dollar bills." Smith's comment prompted gasps from many of the courtroom's Depression-impoverished spectators. Florida dock-builder H. F. Ryder testified that he saw enough money in Capone's Palm Island estate cupboard "to choke an ox."

The final key witness for the prosecution was Fred Reis, cashier of the Cicero gambling house in 1927. Reis placed the hall's profits for 1927 at "around $150,000." Reis testified that he saw Capone when he was taking bets in the hall. "Capone came by and said, 'Hello, Reis.' I said, 'Hello, Al.'” Jacob Grossman asked Reis about 43 cashier's checks, representing the hall's profits, that were purchased from a Cicero bank. Reis testified that he had bought the checks (made out to "J.C. Dunbar," an alias used by Reis) and turned them over to Bobby Barton. Underneath the signature of "J.C. Dunbar" on one of the checks was the signature of Al Capone.

The defense presented its case in a single day. Defense attorneys tried to present Capone as a horse-racing addict who lost as much money as his businesses earned during the years in question. (Gambling losses are only deductible against gambling winnings, so even if the defense testimony was accepted, it would hardly have absolved Capone from his duty to pay taxes on the income from his many businesses.) Bookie Milton Held testified that Capone lost "three or four hundred dollars" at a time betting on horses, and that he was a consistent loser. Oscar Gutter, another bookie, estimated that Capone lost $60,000 betting with him in 1927. After its parade of six bookies had ended, the defense rested its case, having shown that Capone might have lost $327,000 in six years of betting.

In his summation for the defense, Albert Fink told the jury to stand as a bulwark against an oppressive government that was just using the tax law "as a means to stow Al Capone away." He described the government's evidence against his client as "chaff" that "does not prove gross income." He urged the jury not convict Capone merely because he was "a bad man": "He may be the worst man who ever lived, but there is not a scintilla of evidence that he willfully attempted to defraud the government out of income tax." Then Fink switched gears and concluded by arguing that far from being a bad man, Capone was "open-handed," "generous," and "the kind of man who never fails a friend." Capone was not the type of "miser" or "tinhorn" or "piker" who would try to cheat the government out of its due, Fink said. Michael Ahern, summing second for the defense, returned to the theme of an oppressive government bent on using questionable means to put Capone in jail to satisfy the newspapers and the persecutors. "You, gentlemen," he told the jury, "are the last barrier between the defendant and the encroachment and perversion of the government and the law in this case."

Prosecutor Jacob Grossman noted in his summation that Capone described himself as "a gambler, a realtor, a cleaner and a presser and a dog race-track owner." He pointed out that the defendant lived "like a bejeweled prince" and "spent thousands of dollars without thinking twice." Samuel Clawson emphasized the incriminating nature of the "Mattingly letter," which he said proved that Capone knew he was guilty of tax evasion. He added that "even a child" could deduce from Capone's lavish lifestyle that he had a huge income. The last lawyer to address the jury was U. S. Attorney George Johnson. Johnson said, "This is a case that future generations will remember....They will remember it because it will establish whether a man can so conduct his affairs that he is above the government and above the law."

At 2:42 P.M. on October 18, the jury left the courtroom to begin its deliberations. They filed back into the courtroom eight hours later with their verdict in hand. When the clerk pronounced the word "Guilty" (on the charge of tax evasion for 1925) reporters dashed to phones to report the news. Six days later, Judge Wilkerson imposed a prison sentence of eleven years, the longest term ever handed down for tax evasion. Capone, as he was led in handcuffs to a courtroom elevator, yelled, "I'm not through fighting yet."

Appeals failed. Capone served time in federal penitentiaries in Atlanta and at Alcatraz. In November 1939, after serving less than eight years, he was released while suffering from paresis caused by untreated syphilis. On January 25, 1947, Capone died of a stroke in Palm Island, Florida.