Senator SPECTER. The subcommittee hearing will now proceed, and we welcome the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Director Freeh, would you rise, please, to take the oath?

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir.

Senator SPECTER. Do you solemnly swear that the testimony you give before this Senate subcommittee will be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

Mr. FREEH. I do.

Senator SPECTER. You may be seated, Director Freeh.

We have your full statement, which will be made a part of the record, and I know from our prior discussions your interest in proceeding with the entire statement, and I think that is entirely warranted under the circumstances. You may proceed at your leisure.

TESTIMONY OF HON. LOUIS J. FREEH, DIRECTOR, FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, WASHINGTON, DC

Mr. FREEH. Thank you very much, Senator, and good morning to all the distinguished members of this panel. I am pleased to testify before you this morning concerning the role of the FBI in the events at Ruby Ridge and the substantial reforms which I have made as a result of the serious deficiencies of the FBI with respect to that crisis.

I welcome the opportunity to appear before this distinguished subcommittee. Only through a public discussion of these issues can we assure the public's confidence in the FBI and law enforcement.

Ruby Ridge has become synonymous with tragedy, given the deaths there of a decorated deputy U.S. marshal, a young boy, and a boy's mother. It has also become synonymous with the exaggerated application of Federal law enforcement. Both conclusions seem justified.

At Ruby Ridge, the FBI did not perform at the level which the American people expect or deserve from their FBI. Indeed, for the FBI, Ruby Ridge was a series of terribly flawed law enforcement operations with tragic consequences.

We know today that law enforcement overreacted at Ruby Ridge. FBI officials promulgated rules of engagement that were reasonably subject to interpretation that would permit a violation of FBI policy and the Constitution—rules that could have even caused worse consequences than actually occurred, rules of engagement that I will never allow the FBI to use again.

There was a trail of serious operational mistakes that went from the mountains of northern Idaho to FBI headquarters and back out to a Federal courtroom in Idaho. Today, there are allegations that a cover-up occurred, allegations that, if proven, shake the very foundation of integrity upon which the FBI is built.

Although I was not FBI Director when the Rub Ridge crisis occurred, I am sincerely disappointed with the FBI's performance during the crisis, and especially the aftermath. These hearings have only served to confirm that belief. The FBI has, however, learned from its mistakes. I have changed almost every aspect of the FBI's crisis response structure and modified or promulgated new policies and procedures to address the flaws and shortcomings apparent to the FBI's response. I am committed to ensuring that the tragedies of Ruby Ridge never again happen.

As you are aware, the FBI responded to Ruby Ridge subsequent to the Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms investigation of Randy Weaver. The FBI response came after the U.S. Marshals Service had conducted an 18-month investigation and surveillance of Mr. Weaver. The FBI responded to Ruby Ridge on August 21, 1992, after the tragic murder of Deputy U.S. Marshal William Degan.

It is important to keep these facts in mind. Deputy Marshal Degan's death, as well as additional information provided by other law enforcement agencies—which other witnesses have described here—formed the basis upon which the FBI responded in Idaho in August 1992.

On April 5 of this year, after reviewing the Department of Justice's performance at Ruby Ridge, the Deputy Attorney General determined that the threat posed by Randy Weaver was exaggerated. She also determined that repetition of those exaggerations to the FBI led to a higher threat assessment than otherwise might have been made.

It is important to understand, however, that in August 1992, the FBI acted upon information that had been provided by other law enforcement agencies. Based upon that information, the FBI believed that it was facing a very grave threat in Idaho, a threat that required a prompt response. Now, with all of the benefits of hindsight, the FBI's response clearly was an overreaction. In future situations, I will make a more independent assessment of such threats before the FBI acts.

As I have stated many times before, Vicki Weaver's death was tragic but accidental. I fully appreciate the fact that three children have been left without their mother as a result of what occurred at Ruby Ridge. On behalf of the FBI, I wish to express my regret and sorrow for Mrs. Weaver's death. Moreover, the FBI fully supports the settlement with the Weaver family that the Department of Justice negotiated. For the FBI, however, the settlement does not bring any sense of closure to the stark tragedy of Vicki Weaver's death. Rather, her death will always be a haunting reminder to the FBI to take every possible step to avoid tragedy, even in the most dangerous situations.

I also want to express my heartfelt condolences to Mrs. Degan. This country asked her husband to make the ultimate sacrifice. What happened at Ruby Ridge and its aftermath fails to honor the price paid by this dedicated public servant. We as a nation should never forget those left behind when an officer dies in the line of duty.

At Ruby Ridge, the Hostage Rescue Team was operating in accordance with rules of engagement that were reasonably subject to interpretation that would permit a violation of FBI policy and the Constitution. Those rules said that, under certain circumstances, persons "can and should" be the subject of deadly force. Those rules of engagement were contrary to law and FBI policy. Moreover, some FBI SWAT personnel on scene, who you heard from last week in this room, interpreted the rules as a shoot-on-sight policy, which they knew was inconsistent with the FBI's deadly force policy. Such confusion is entirely unacceptable.

According to Special Agent Lon Horiuchi, the HRT sniper who accidentally shot Ms. Weaver, he fired two shots on August 22, both pursuant to the FBI's deadly force policy. He has testified that he did not shoot pursuant to the rules of engagement that I have just mentioned.

The shot that killed Ms. Weaver was the second that Special agent Horiuchi fired. He testified that it was not intended for Ms.

Weaver and was not fired at her.

In discussing Special Agent Horiuchi's second shot, I am not saying that I approve of it. I am not trying to justify it. I am not saying that I would have taken it. I am not saying that others should do what he did. I am certainly not saying that in a future similar set of circumstances FBI agents or law enforcement officers should take such a shot. The FBI will strive and train to avoid such tragic results, whenever humanly possible.

Indeed, the constitutionality of Special Agent Horiuchi's second shot is a very close and very difficult question. It is not a matter that can be addressed in black-and-white terms. It cannot be answered categorically or with a high degree of certainty.

On careful balance, however, I believe that Special Agent Horiuchi's second shot was constitutional. Under all the circumstances that Special Agent Horiuchi faced on August 22, 1992, and based on all the evidence, I do not believe that it was unlawful in that time and place for him to take the second shot.

It is important to remember that two different components of the Department of Justice have reviewed the circumstances leading to Vicki Weaver's unfortunate death. Both those components—the Office of Professional Responsibility and the Civil Rights Division— independently determined that there was no basis upon which to conclude that she had been shot intentionally or unlawfully. Both determined by their analyses that the second shot was not unconstitutional.

In January of this year, I disciplined or proposed discipline for 12 FBI employees for their conduct related to the incident at Ruby Ridge and the subsequent prosecution of Messrs. Weaver and Harris. My disciplinary action followed an FBI administrative review of the conduct of those employees. My action also followed reviews by the Department of Justice Office of Professional Responsibility and the Civil Rights Division, which independently determined that criminal prosecution was not warranted. All of these actions, including my own, relied upon a task force investigation that was directly supervised by the Department of Justice and a report that was written by Department of Justice attorneys, not FBI special agents.

I too determined that the 12 FBI employees did not commit any crimes or intentional misconduct. Nevertheless, I concluded that those employees had demonstrated inadequate performance, improper judgment, neglect of duty, and failure to exert proper managerial oversight. Accordingly, I imposed or proposed discipline ranging from an oral reprimand or written censure to written censure with suspension from duty. At that time, I believed the discipline imposed or proposed was commensurate with the factual basis for the imposition of that discipline.

The discipline imposed was, as I said, based upon facts that had been determined at the time. Discipline was not imposed on the basis of showing favor to one person, or another or on the basis of speculation, or in order for me to render a "popular" decision. Indeed, discipline was imposed on the basis of the record before me and precedent, which is a fundamental component of the FBI's administrative summary process. The reliance upon precedent is a basic matter of due process and fairness. That reliance ensures that people who commit similar offenses are punished in a similar manner. In imposing and proposing discipline this past January, that's what I was trying to do.

In January, I imposed and proposed discipline on the basis of what I believed to be a complete report. Ongoing investigations, which I obviously cannot discuss in detail, may prove that report was not as compete as I believed.

I intend to be fair about this matter, but any final action must be based upon a full and accurate reporting of the facts.

Larry Potts was one of the 12 FBI employees included in my disciplinary decisions this past January. He received a letter of censure for failure to provide proper oversight with regard to the rules of engagement employed at Ruby Ridge. It should be noted that the administrative summary report recommended that neither Mr. Potts nor Mr Coulson be disciplined. I disagreed with that conclusion based upon the facts as I found them.

At the time I disciplined Mr. Potts, he was the Acting Deputy Director. Shortly thereafter, I sought to promote him to be Deputy Director of the FBI.

In pressing for Mr. Potts' appointment as Deputy Director, I was not trying to minimize or downplay the significance of the punishment which I had imposed upon him. I did not appoint him Deputy Director simply because he is a friend

In determining whether to appoint Larry Potts to be the Deputy Director, I considered his many years of public service to the Nation and to law enforcement. I considered the esteem in which subordinates, superiors, counterparts, and colleagues hold him. I considered his vast accomplishments in the FBI, including our work together in the VANPAC investigation for which President Bush personally awarded Mr. Potts an Exceptional Leadership Award in the Rose Garden.

I consulted with numerous people inside and outside the FBI, including judges, a former Attorney General, prosecutors, investigators in other agencies, and leaders of Federal, State, and local law enforcement. It was their consensus that Larry Potts was an excellent and progressive leader, highly qualified to be Deputy Director. Like them, I placed great trust and confidence in Mr. Potts.

Looking back, I recognize that I was not sufficiently sensitive to the appearance created by my decision to discipline and simultaneously promote Mr. Potts. Thus, I made a mistake in promoting Mr. Potts. I take full responsibility for that decision, and I alone should be held accountable for it.

As the subcommittee is aware, two criminal investigations relating to Ruby Ridge and its aftermath are currently pending. One is in Boundary County, ID, where Prosecutor Randall Day is investigating the deaths of Vicki Weaver, Sammy Weaver, and Deputy Degan. The other is a Federal investigation here in Washington, DC. It focuses upon actions allegedly taken by FBI employees during and after the Ruby Ridge siege.

I do not wish to prejudice either investigation. I also do not want to prejudge any one who may be a subject of those investigations. I must stress, however, that the cover-up allegations are quite serious and go to the very heart of what FBI agents are supposed to do—seek the truth. There is nothing more grievous and shocking than an allegation that an FBI agent has committed perjury or obstruction of justice.

The subcommittee and the American people should have no doubt that I will swiftly and decisively address any misconduct which was committed by any FBI employees. In that regard, my actions will be consistent with the "bright line ethical and legal standard" that I established for FBI employees in January 1994.

Any such actions, however, cannot occur until the investigation is complete and all of the facts are known.

The FBI has learned the lessons of Ruby Ridge. As the subcommittee has already heard, we have changed policies and procedures to prevent similar, tragic mistakes in the future. I have prepared a handout describing these reforms. I would respectfully ask that that and the other charts be made a part of this official record.

Senator SPECTER. They all will be made a part of the record as requested, Director Freeh.

[The information follows:]

Mr. FREEH. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

First, I have ended forever the use of rules of engagement by the FBI. The FBI will govern its use of deadly force by the Department of Justice deadly force policy, which permits the use of deadly force only in the face of imminent death or serious physical injury to the officer or another person. In a moment, I will describe that in greater detail.

Never again will rules of engagement be open to an interpretation which can expand the deadly force policy. In future crises, there will be no confusion, as there was at Ruby Ridge, about the interplay between deadly force policy and rules of engagement. The standard deadly force policy will be the sole standard, although on-scene commanders will be permitted to further restrict the use of deadly force as necessary. In addition, if it is necessary to communicate to agents an especially heightened risk, that will be done through separate threat advisories.

In the aftermath of Ruby Ridge, there were problems relating to the shooting incident review conducted by the FBI in 1992. That review inaccurately and incompletely analyzed the accidental shooting death of Vicki Weaver. The person in charge of that review had participated in FBI headquarter oversight of the Ruby Ridge response and was then asked to assess the validity of the shootings that occurred.

Shooting investigations must be full and fair. They must be conducted by persons who do not have even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

Thus, on April 3, 1995, I announced revisions to the FBI's shooting review policy in order to ensure the complete and accurate investigation of shootings. Among other things, it raised the executive level of review regarding shooting incidents; it placed investigative responsibility in the FBI's Inspection Division; it established new protocols governing the conduct of postshooting inquiries; and included, for the first time, Department of Justice attorney representation on the Shooting Incident Review Group.

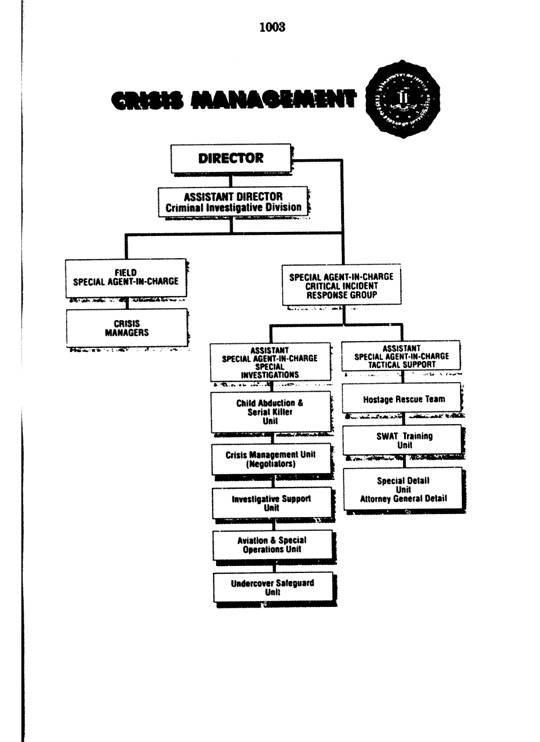

The third and most significant major change I made is the creation of the Critical Incident Response Group [CIRGI, which I established in 1994. I have provided to the subcommittee another chart reflecting that establishment.

Without question, Ruby Ridge demonstrated that the FBI's crisis management structure was inadequate and terribly flawed. The new CIRG ensures the FBI's experienced senior leadership's responsibility and directly establishes accountability on specific individuals, including myself, for crisis management. CIRG fully integrates crisis negotiators and the HRT and joins them at the same level in a unified command. The structure which I have established ensures an equal tension between our tactical and nontactical components, with a special agent in charge and myself overseeing the process. As part of that integration, I have ordered that, whenever HRT deploys, CIRG negotiators and other resources must deploy with them.

The members of HRT are not commandos. They are special agents of the FBI. Their goal has always been to save lives. Like any FBI special agent, the members of HRT carry badges and handcuffs. Their objective is identical to that of law enforcement officers around the country—to arrest safely those responsible for crimes and assist in their prosecution. The members of HRT, however, perform these tasks in crisis situations.

The HRT is a unique and necessary law enforcement response capability. Nevertheless, the simple fact that HRT exists does not mean that it must be used, especially if we do not have to use it.

The HRT should not be used reflexively. I approach the use of HRT conservatively and seek independent FBI assessments before its use. Indeed, I cannot envision utilizing the HRT unless I am personally satisfied that it is necessary and appropriate to do so.

Through the integrated response that CIRG provides, I am confident that the FBI will better perform its duties to resolve future crisis situations without loss of life.

Finally, I have increased the crisis management training provided to FBI executive who will serve as on scene commanders in crisis situations. Attorney General Reno, the Deputy Attorney General, and I have received this training. This was not the case be-fore. It has also been provided to other senior Department of Justice officials and a large cadre of FBI field commanders. I believe that this training effort will help ensure the peaceful resolution of future crises.

Some crisis management reforms have been established throughout the Department of Justice. In my capacity as Director of Investigative Agency Policies, I have issued Resolutions 12, 13, and 14, which resulted from consensus recommendations of the investigative agencies of the Department of Justice. These resolutions were created at the request of the Attorney General, and she has now approved them.

Resolution 12 established policy to govern agencies' use of the FBI's crisis management resources in the field, as well as components of CIRG. I believe that Resolution 12 clearly establishes lines of authority during crises and will avert confusion when a crisis occurs. Additionally, Resolution 12 requires other Department of Justice investigative agencies to consult and coordinate with the FBI when the degree of threat in one of their cases requires and allows for preplanning.

Resolution 13 established a general policy concerning the conduct of postshooting incident reviews. I previously described changes to FBI policy in this matter. Resolution 13 ensures that Department of Justice agencies will conduct thorough and objective shooting incident reviews, which subsequently are reviewed further in order to ensure fairness and accuracy.

Many months ago, the Attorney General tasked the Office of Investigative Agency Policies to draft a uniform deadly force policy for her consideration. Beginning in January of this year and after 9 months of research, discussion, and analysis between the agencies compromising the Office of Investigative Agency Policies and various components of the Department of Justice, especially the Office of Legal Counsel, Resolution 14, which established a uniform deadly force policy, was issued and the Attorney General has approved it.

The Treasury Department also participated in the negotiations leading to the deadly force policy. Through the efforts of Treasury Under Secretary Noble and his staff, there is now for the first time a uniform deadly force policy that governs the actions of Treasury Department and Justice Department law enforcement officers. That policy permits deadly force to be used "when the officer has probable cause to believe that the subject of such force poses an imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to the officer or to another person."

Several times during these hearings, the issue of whether the FBI should investigate itself has arisen. In assessing this issue, the subcommittee should consider the FBI's history in this regard. Unlike most police forces, the FBI has not one, but two independent watchdogs that provide oversight of the FBI's employees and activities.

In coordination with the Department of Justice Office of Professional Responsibility since 1976, the FBI has had a long and distinguished record of successfully investigating alleged misconduct by its employees. This record of success includes matters of great significance which are further detailed in my prepared statement.

The Attorney General issued an order on November 8, 1994, which makes clear that, in addition to the Department of Justice Office of Professional responsibility, the office of the inspector general also performs oversight of the FBI. That oversight is occurring in connection with the FBI's performance in the Ames internal security investigation. Indeed, the office of the inspector general may request authority from the Deputy Attorney General to take responsibility for investigating a particular allegation under investigation by the FBI's OPR. Further, the FBI can recuse itself from a particular investigation, if appropriate, and this has been recently done in a high-profile case.

The success of the FBI's internal investigations is due, in large p art, to the support and participation of FBI employees. Experience has shown that thorough, effective internal investigations require the expertise of agents who are intimately familiar with FBI's structure and procedures. Furthermore, an internal policing function is necessary for me to manage the agency successfully, to establish investigative and ethical priorities, and to demonstrate to the agency, the Congress, and the American people that improper conduct by FBI employees will be dealt with effectively.

In partnership with the Department of Justice OPR and the office of inspector general, the FBI has been and remains committed to an effective internal security program. Based upon my 20 years of experience inside and outside of the FBI, I have reached two conclusions: First, the FBI is the best investigative agency in the world; second, the FBI has enjoyed extraordinary success in policing itself with active, independent oversight.

The subcommittee should also consider the experience and uniformity of major police departments around the United States. They have learned from hard experience that police integrity is absolutely dependent on police being responsible and accountable to investigate themselves with independent oversight, exactly like the FBI. I have prepared a chart with some notes reflecting the consistency among major police departments with respect to at least initially having the responsibility of investigating themselves.

In conclusion, serious mistakes occurred with regard to the Ruby Ridge incident. Some of those mistakes should have been avoided and were not. For those, the FBI offers not excuses, but rather the facts and significant reforms.

Intentional misconduct is a different matter altogether. As I stated before, I assure the subcommittee and the American people that I will swiftly and decisively deal with anyone or any person who the facts show committed any misconduct.

With the arsenals at the disposal of criminals in our Nation today, everyone should understand that law enforcement officers have a very dangerous job to do—a fact noted many times by this committee. Since becoming Director of the FBI in September 1993, I have attended the funerals of three FBI special agents and numerous State and local law enforcement officers who were killed in the line of duty by criminals with guns. Again, last Friday, I attended a funeral of a young Washington metropolitan police officer, Scott Lewis, killed without provocation in the line of duty. Tomorrow I will attend another funeral for a Maryland State trooper killed Tuesday, again, without provocation.

I have witnessed firsthand the devastation these weapons inflict upon the agents and officers, their families and loved ones. Every week I speak with chiefs of police and sheriffs from around the country who suffer casualties in their ranks at the hands of criminals with guns.

We take our responsibility seriously when we ask the men and women of law enforcement to put themselves in harm's way—people like Deputy U.S. Marshal Bill Degan. As law enforcement leaders and managers, we owe them our complete support and must strive to give them the best guidance possible.

We rely upon the men and women of law enforcement to do their best job under very difficult circumstances. In return for protecting us, we vest them with a measure of discretion and ask them to use their best judgment. Sometimes, as human nature tells us, that judgment maybe imperfect and mistakes will happen.

As long we ask them to be in the arena, to be ready in the middle of the night to take cover behind a tree or a mailbox, to put their lives and well-being of their family in the line of fire, we must show some empathy and compassion for heir human fallibility. This is particularly true as we judge with the calm, well-lighted knowledge of hindsight, far from what the Supreme Court calls "split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain and rapidly evolving."

Mr. Chairman, thank you very much for the indulgence of letting me read a lengthy statement. I am happy to answer any of your questions, sir.

Senator SPECTER. Thank you, Director Freeh, for that statement. I think it appropriate to note that today marks the 6-month anniversary since the bombing of the Federal building in Oklahoma City, and I was particularly moved by your comments about the funerals which you have attended for law enforcement officers, which reminded me of the many funerals which I attended, when I was district attorney for Philadelphia for police officers who were killed in the line of duty. And I do believe that you are correct that we have to look at the issues with compassion and understanding and recognize the discretion which is necessary for law enforcement officers who are in the field.

At the same time, I know you recognize from our extended private conversations that law enforcement has the responsibility to enforce not only the criminal law dealing with violent criminals, but also to enforce the constitutional law and to enforce the law against violent criminals within the constitutional context.

We applaud the actions which you have already taken on an interim basis, Director Freeh, noting your revision of the rules regarding the Hostage Rescue Teams shortly after they testified before this committee and your statement, sometime ago, that rules of engagement would be modified only on your direct order and the action taken by the Department of Justice yesterday in promulgating the new rules with respect to deadly force.

That is the take-off point for my round of questions which will constitute 20 minutes, which we have established in collaboration with the distinguished ranking member.

Director Freeh, in reviewing the new rules on deadly force, I was impressed with an introductory statement that the Department deliberately did not formulate this policy to authorize force up to constitutional or other legal limits. In examining the rules in some detail, I have a question about whether these rules are within the guidelines of the U.S. Supreme Court in the two cases, Garner and Graham, because of the use of the word imminent, which the description by the Department of Justice says has a broader meaning than immediate or instantaneous, and the guidelines say this concept of imminent should be understood to be elastic, that is, involving a period of time dependent on the circumstances rather than the fixed point of time implicit in the concept of immediate or instantaneous.

As you and I have discussed preliminarily—and we can get into it in some detail at a later stage—imminent is broader than immediate, and the Supreme Court cases talk about immediate.

I begin as a starting point, in your judgment would the second shot fired by Agent Horiuchi which killed Ms. Vicki Weaver be in violation of the new FBI policy on deadly force?

Mr. FREEH. Mr. Chairman, my view of your question would be that under the objective reasonableness test, which Garner, of course, has us apply in those situations, the reformulation of the deadly force policy and the insertion of the word imminent would not, in my view, make that second shot unconstitutional.

Senator SPECTER. Well, Director Freeh, let me tell you directly that I think the rules have to be sufficiently clear to make that second shot unconstitutional. And let me take up the second shot with you in the context of the third report which you did not mention. You talked about OPR and civil rights. But the Department of Justice task force came to a different conclusion.

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir.

Senator SPECTER. Director Freeh, I understand that you have already commented that the rules of engagement on their face—that is, the statement if you see a male armed, you could and should shoot to kill—that those rules of engagement are on the face unconstitutional. Is that your current view?

Mr. FREEH. Without any facts or circumstances which, of course, would be part of the calculus of reasonable objectiveness, those words standing alone on their face surely would be unconstitutional.

Senator SPECTER. Well, we agree on that. The Department of Justice task force makes these comments, among many others: At the time of the second shot, Harris and others outside the cabin were retreating, not attacking. These facts undercut the immediacy of the threat that Harris posed to Horiuchi and his colleagues. We believe that his second shot was taken without regard for the safety of others near Harris. In sum, even giving deference to Horiuchi's judgment, we do not find that the second shot was based on a reasonable fear of an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others. We believe the shot was unnecessarily dangerous and should not have been taken.

With respect to the rules of engagement, Director Freeh, when Deputy Attorney General Gorelick testified yesterday, she said, "I understand Agent Horiuchi testified that he did not act under the rules of engagement. I also believe that the rules of engagement had to have affected the point of view that he brought to that incident."

Do you disagree with or agree with Ms. Gorelick that the rules of engagement had to have affected Mr. Horiuchi's point of view?

Mr. FREEH. No, I don't, sir. I think that if you look at the cold record—and, unfortunately, we're relegated to the cold record with respect to his testimony—

Senator SPECTER. When you say no, do you agree or not agree with Ms. Gorelick?

Mr. FREEH. I do not. I think that if you read the direct and cross-examination, which is all we have right now with respect to his testimony, although he says he was aware of the rules of engagement—and we certainly know that he was because he was briefed on them—his testimony both on direct and cross-examination is that he reserved to himself the decision to make that shot.

If the test under Garner is an objective reasonable test—and that is what Justice White says—even if he believed that he was operating under the rules of engagement, whatever his motive or intent was would be irrelevant to the issue of constitutionality if, under the objective reasonableness test, everything that he knew at that time was consistent with justifying the shot. So I think that although he knew the rule and only he can say how much it influenced him—and he said that it did not—the test of constitutionality would still come down on the side of lawful—although I admit it is a very close question and I understand the arguments to the contrary.

Senator SPECTER. Well, Director Freeh, where you have a standard of "could and should shoot to kill an armed male" and Agent Horiuchi knows that, how can you say as a matter of just basic common sense that it would not have affected his judgment under the circumstances where he made that second shot?

Mr. FREEH. Mr. Chairman, I obviously can't say that with certainty. I can't get inside the mind of Agent Horiuchi. But I do have his testimony, and we all have his testimony to read. And he says on the record that although he knew about the rules of engagement, he certainly was briefed on them, when he took the shot took it under a set of conditions and circumstances which would meet, in my view, the objective reasonableness test.

Can we say with certainty that knowing about those rules did not influence him? No, we can't. But we can say, at least I can say that, based on my review of the record, he had enough circumstances to meet a constitutional standard.

Senator SPECTER. Director Freeh, in your prepared statement, you distance yourself about as far as you can go in the context where you say, on pages 4 and 5, "In discussing Special Agent Horiuchi's second shot, I am not saying that I approve of it. I am not trying to justify it. I am not saying that I would have taken it. I am not saying that others should do what he did. I am certainly not saying that in a future similar set of circumstances FBI agents or law enforcement officers should take such a shot."

Now, would you, in Special Agent Horiuchi's position, take the shot if you were confronted with those facts today?

Mr. FREEH. I don't know. I think that's a situation that I probably couldn't answer unless I was there. And I don't think anybody in this room could answer that unless they were there.

Senator SPECTER. Well, you say, "I am not saying that in a future similar set of circumstances FBI agents or law enforcement officers should take such a shot." Would you say to your subordinates that they should take the shot, that they should not take the shot—

Mr. FREEH. No, I think

Senator SPECTER [continuing]. Or would you not pass judgment? In this case, you have a crystal set of facts. And I appreciate the impossibility of duplicating or replicating an exact set of facts in the future. And any deviation may be sufficient to change the conclusion on constitutionality. But you are the Director of the FBI, and you have studied this case with intensity. And you have just come up with a new policy for the use of deadly force. And I think you ought to be in a position to say whether or not, if faced with this identical set of circumstances, you would instruct your agents to shoot or not to shoot.

Mr. FREEH. I can't answer that question. I think with all of the hindsight that we now import into these situations, we certainly look at these facts now 2 ½ years away from the incident based on these understood facts. In a training protocol for new agents or experienced agents in the FBI Academy, I think we will train them and teach them that this is a retreat situation, perhaps, and one where the perhaps should hesitate or think very carefully about using deadly force. But that's a training protocol which I think we are responsible for, which I think we will do under the new policy.

The insertion of the word imminent is put in there for a particular reason. It is to raise the consciousness and put into the training protocols the important judgment quality of pause and reflection when you can do it in a split second—and sometimes you can't— and hopefully prevent a situation like this from happening again. But that's a hindsight judgment which we have the luxury of making.

Senator SPECTER. I am not yet sure what the judgment is, Director Freeh. You say it is a retreat situation. You used the word perhaps. These set facts are crystallized. And I think that your subordinates are entitled to a judgment from the Director of the FBI as to whether that is a shoot or not shoot under the new rules of deadly force. Which is it?

Mr. FREEH. I think if you wrote this as a training scenario, you would have to think very, very carefully about instructing a shoot outcome. It is the same situation you would have if someone points a loaded gun at you and runs away, not immediately threatening you anymore, but going to a location where they can threaten you. Do you employ deadly force before they reach that situation or not? It is a retreat situation, but maybe the facts indicate that that person is going to turn and fire as soon as they have the protection of cover.

It's a very difficult judgment to make, and I don't think there's an arithmetic solution to all these scenarios. What the scenario should do is challenge the judgment, challenge the thought process, and invoke all of the considerations that have to go into place before people can use deadly force.

Senator SPECTER. Well, Director Freeh, I think you still haven't answered the question. Think very, very carefully about it and the retreat situation. You are the Director. They have to make the judgments on the scene. No set of facts will be identical. But what is your judgment? What do you say? I think this really calls for a yes or no.

Mr. FREEH. As to this particular set of facts?

Senator SPECTER. As to this particular case, as to the second shot which killed Ms. Vicki Weaver under the facts which are crystallized, and you have the new rules of deadly force. I think your subordinates are entitled to a judgment from the Director.

Mr. FREEH. Well, I think it's not the judgment of the Director. I think it's their judgment which has to be employed. But I think the protocol would be to them, if they believed an individual was retreating to a place where they were going to turn and fire on them, they could use deadly force because that's an imminent threat to their safety. If they think the person was retreating to a place where there were children, where return fire could not be made even if the, subject then fired at the agents, the instruction would be not to fire as that person got close to a location where innocent people could be harmed.

The problem we have here, as the subject is moving closer to the house, the shot becomes more unreasonable because of the location—

Senator SPECTER. More unreasonable?

Mr. FREEH. More unreasonable because of the location of children in the house. As he is further away from that location, there is more of an argument for reasonableness. But those are the kinds of critical balances that have to be relegated to the person on the scene making the judgment.

Senator SPECTER. Well, let me approach it one more time one more way. You are on the scene, and all those facts are in your mind. Would you shoot or would you not shoot?

Mr. FREEH. If I thought the person was going to a place of cover where they were going to shoot me and there was no innocent person or a third party in the way of a clean shot and I believed that person was going to shoot me, I would employ deadly force.

Senator SPECTER. Well, would you have thought that person was likely to have shot you under these circumstances?

Mr. FREEH. Under these circumstances? Again, I can't put my place—you're asking me to do something which is impossible. You're asking me put myself in the place of a person with a whole set of different sounds, sights, and circumstances that I can't duplicate for you except in a very conjectural way.

Senator SPECTER. Well, Director Freeh, with respect, I don't think the question does put you in an impossible situation. The question asks you on all the facts at Ruby Ridge and the second shot, knowing all of the facts at hand about what was happening, about the possibilities of total retreat, about the possibilities of the later shot, about the Supreme Court rules, about the new policy for use of deadly force, you are an ex-FBI agent, you are an ex-Federal judge, you have a working knowledge of the Constitution, you are the Director of the FBI, and I think that it is a fair question for one of your subordinates who has to make this judgment to know what the Director would do with 20/20 hindsight and a lot of time to think about it and having studied these new rules of deadly force. And if you decline to answer, so be it.

Mr. FREEH. Senator, I am trying to answer your question. Maybe I'll try it another way.

As that subject got closer to that house, I would not have taken the shot. Separate and apart from that louse, if I believed that the subject was about to shoot at a helicopter—and that's what the testimony is—I would have employed deadly force at that point.

If after the person pointed a gun at the helicopter and I believed at the time that he was going to shoot and that person then ran away for cover, I'm not so sure that I would employ deadly force in that situation. I would certainly not employ it if he moved inside a cabin or very close to a cabin where I knew there were children who could be harmed.

Senator SPECTER. I take that as a qualified no, and I am going to move on.

I think you have pretty well said it, but I would like to ask you directly if at this point you had it all to do over again, would you not promote Mr. Potts to be Deputy Director of the FBI.

Mr. FREEH. Yes. I would not do so. That was a mistake that I made and my mistake alone.

Senator SPECTER. Director Freeh, a number of the members have had considerable concern about the FBI investigating itself—and it is a subject you have addressed—and concern about the treatment of Mr. Potts both in terms of possible preferential treatment on his promotion and concerns about possible inappropriate treatment when he was suspended.

This is a subject which you and I have discussed at some length on a couple of occasions. Yesterday, Ms. Gorelick testified that there is a statute which authorizes suspension and loss of pay when there is reasonable grounds to believe someone has committed a crime. But what is the justification for putting Mr. Potts in the position he is in now with a long waiting period, a projection of what I understand to be 8 months before there may be a resolution by the U.S. attorney, in a context where there has just been a criminal referral? Is that a fair policy to apply to Mr. Potts?

Mr. FREEH. The fairness of the policy actually depends on what the strength of the allegations are and what the evidence is. Unfortunately, I’m not privy to that.

Senator SPECTER. Well, how can you have issued the order of suspension or the administrative action you took without knowing the answer to that question?

Mr. FREEH. I was provided some information—

Senator SPECTER. My time is up, so this will be my final question.

Mr. FREEH. I was provided some information with respect to the allegations about Mr. Potts when I suspended him. I was not for instance, provided with the information which this committee has elicited from the prosecutor, which are the notes which you questioned Mr. Potts about yesterday. I did not have them. I did not know about them at the time of the suspension.

However, it was my decision to suspend him based upon the recommendation of the head of the Department of Justice OPR, Mr. Shaheen, who told me then that it is the invariable policy of the Department of Justice and had been his practice with every Attorney General to suspend individuals whom OPR recommend for criminal referral. Although it was my choice to make, when he made that recommendation I thought it was my obligation, and I did not decide to do otherwise.

Senator SPECTER. Thank you, Director Freeh.

Senator Kohl.

Senator KOHL.

I thank you, Mr. Chairman, and, Director Freeh, it is a privilege to have you in front of us today. The organization has come under attack in recent months, but in my opinion, you, Director Freeh, are doing an outstanding job as FBI Director. We must always remember that you inherited Ruby Ridge, and I believe that there is no one better suited to implement reforms than you are.

I would also like to commend Senator Specter today for his dogged pursuit of these hearings, our chief special counsel, Mary McLaughlin, for her tireless efforts, and the entire panel for demonstrating that no one should be targeted for his or her beliefs and also that no one is above the law.

I would like to take up the question of Potts which was initiated by Senator Specter. He asked you whether or not you would promote Potts if you had that decision to make today, and you flat out said no. In your statement, you said that you recognized that you had not been sufficiently sensitive to the appearances created by your decision to discipline and then to promote Mr. Potts.

Does that stand as the reason why you would not promote him today if you had that opportunity again?

Mr. FREEH. Senator, that would certainly be a central reason. I would certainly add to that the concurrent reason that there are allegations, at least in the form of a criminal referral, against Mr. Potts and others. That is only to say that there are allegations, and, of course, we have to await the development of those facts. But certainly with the added fact of those allegations, it would not be any type of a course of action that I would propose or anybody else would accept.

Senator KOHL.

I would like to go a little bit further, and it relates to the question as to whether or not you had a blind spot when it came to Mr. Potts. In your statement, you said that at Ruby Ridge, where Mr. Potts was the head person in charge in the hierarchy, "the rules of engagement were contrary to law and the FBI policy. Moreover, some FBI SWAT personnel on scene, who you heard from last week in this room, interpreted the rules as a 'shoot on sight' policy, which they knew was inconsistent with the FBI's deadly force policy. Such confusion is entirely unacceptable."

You went on to say that "At Ruby Ridge, the FBI did not perform at the level which the American people expect or deserve from their FBI. Indeed, for the FBI, Ruby Ridge was a series of terribly flawed law enforcement operations with tragic consequences."

Now, we will debate, I suppose forever, whether or not Mr. Potts personally promulgated the rules of engagement, but there is no question that he was the head person on the scene in charge. Now, in view of that and knowing that as you did, how could you promote him to be the Deputy Director?

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir. Senator, I would not call him the person on the scene in charge. We did have an on-the-scene commander, SAC Gene Glenn, who was a very respected and very able—

Senator KOHL.

But he was the person in charge if, in fact, 2,000 miles away, but he was the person in charge. Is that a correct statement?

Mr. FREEH. You are certainly correct. He had overall responsibility. However, I'm of the mind that you can't manage a crisis from 3,000 miles away. You can do certain things to impact it. You can certainly do certain things to improve or worsen it. But you are not the person in charge of the scene.

The problem with our Denver agents who you heard last week was that no one ever sat down with them and told them that these were not a shoot on sight policy. That wasn't anybody's obligation in Washington. That was the obligation of the field commander to take all of his people together and say, look, these rules do not mean what they say they mean, which is shoot on sight. That was an obligation that the field commander had.

As to Mr. Potts, I found that he had a serious failure in terms of not forwarding and finishing and completing the conversations he began with Rogers and Glenn to finalize those rules. But the implementation of those rules and, more important, the explanation of those rules to the people on the ground had to rest with the field commander.

So when I balanced who did what on the facts that I found them, I thought what Mr. Potts failed to do was very serious, because he had overall responsibility. But I felt that the actual recommendation of the rules, the carrying out of the rules, and the failure to tell the troops what they meant was nothing anybody expected to be done in Washington. That had to be done in the field.

Senator KOHL.

Well, this is true, but he was in charge. He was the man in charge of the overall operation, which you have described as a terribly flawed, bungled, tragic affair. And from that point he winds up getting promoted?

Mr. FREEH. Senator, my view at the time—

Senator KOHL And you call it, well, it was a question of appearance. I find it hard not to accept that there was more than just appearances involved. There was, in fact, performance or the apparent lack of performance. And I find it hard to understand how with that kind of a situation hanging over Mr. Potts, not resolved, that you would decide to promote him to be the Deputy Director of the FBI.

Mr. FREEH. Senator, I defer to your judgment. I think your judgment was correct. Mine was wrong at the time. I think I didn't correctly balance all the factors. But at the time, I picked who I believed was the most competent individual who had the same view of what the FBI should do as myself, who I had complete trust and loyalty in, which you need in a deputy. This was a person who I worked with for 16 months, traveling from motel to motel room, solving the investigation of a judge who was murdered and a civil rights leader who was murdered. There was nobody in the FBI in 1991 who could have solved that case, in my view, except Mr. POTTS. And based on my own personal experience with him and everyone else's, I moved to promote him.

Maybe I did have a blind spot. Was he my friend? He certainly was. He is now. I still believed at the time that he was the best person to be Deputy Director, and obviously that was an incorrect decision and I'm responsible for it.

Senator KOHL.

All right, Director Freeh.

Director Freeh, the American people have a right to believe that the FBI can properly investigate itself, and I believe that there are probably not five people who followed these hearings who believe that the FBI has done a good job investigating itself with respect to Ruby Ridge. We have listened to your testimony, and it still is not clear that you have done enough to ensure that in the future agents won't continue to investigate their friends, their colleagues, and those who sit on their promotion boards.

So, tell us, Director Freeh, if another Ruby Ridge mess comes along, what assurances do we have that the FBI won't again take 3 years, issues a series of inadequate reports, and not get to the bottom of what happened?

Mr. FREEH. I think if we had another Ruby Ridge today where high officials of the FBI are implicated and possibly by appearance sake incapable of investigating, in effect, themselves, I would certainly not hesitate to recuse the FBI from that investigation and ask, for instance, our inspector general to take it up. I have done that recently in one case.

It is not a practice, I must tell you honestly, that I will regularly follow because I think that it is critical for the agency to be responsible, at least in the first instance, for its own integrity. But if we have a situation where the Deputy Director, Assistant Directors, obviously if the Director is the subject of some—forget about criminal, but some administrative action that has to be administratively investigated, it probably is a better idea to have an independent agency to do that. And we have the framework set up in the Department of Justice to do that now. It is not something that I would routinely do because I think it takes away the obligation to be responsible in the first instance for our own integrity. And every police department in the country has that responsibility. But I think there are cases—and Ruby Ridge certainly might have been one—where because of the officials involved, for appearances sake and for practical sake, we should rely upon the Attorney General's November 1994 order and take ourselves out of the picture. And I will not hesitate to do that in those cases.

Senator KOHL.

So you are saying with respect to the investigative process it has not done a good job? Maybe the word failed is too strong a word to use, but the internal investigative process at Ruby Ridge that the FBI has employed you would describe as flawed, failed, inadequate, unresponsive? What?

Mr. FREEH. All those words. The shooting incident review—

Senator KOHL.

And what is it in the system that is going to change?

Mr. FREEH. Well, I think we have a mechanism in the system already that protects the integrity of our investigations. We have an office of the OPR in the Department of Justice and a separate office in the inspector general who monitor what we do, who in many cases initiate investigations, and in some cases investigate the allegations solely by themselves using FBI agents or using postal inspectors, as in a current case.

Those structures I think are adequately suited for giving us the ability to investigate ourselves. In a special case, in a case where high officials of the FBI are implicated, I think that is an opportunity to take advantage of the Attorney General's order, the 1994 order, and ask the inspector general to come in and take over complete responsibility.

I don't think there will be a lot of those cases. I hope there won't be. But I think in certain instances—and Ruby Ridge has all the appearances of that incident—we might want to rely on an "outside mechanism. But that mechanism exists now.

Senator KOHL.

Just finally, is there any adequate explanation, in your opinion, as to why it has taken 3 years now to wait for a full accounting of what happened at Ruby Ridge? In fact, this Senate investigation is probably the fullest accounting that we have received so far.

Mr. FREEH. Unfortunately, the first investigation did not start until the trial was completed, so that was an initial delay of great significance. The subsequent investigations unfortunately have taken a lot of time. The intent was to be thorough and complete. Obviously, the investigations were neither.

I cannot give you a good reason except a mechanism that did not work very well in this case but I think has been fixed and will be monitored and closely adjusted when I think that has to be done in the future.

Senator KOHL.

All right. Mr. Freeh, over the last few weeks, every FBI agent who has testified has told us that the rules of engagement had no impact on the events at Ruby Ridge. In their opinion, the rules might be unconstitutional as written, but the Hostage Rescue Team snipers knew how to properly apply them.

I find this hard to believe. We cannot help but think that the rules of engagement impacted the snipers in some way. Even Ms. Gorelick testified yesterday that she believes that they had some effect on the snipers' state of mind.

Let me read to you what some of the Hostage Rescue Team Snipers said was their understanding of the rules of engagement. Dale Monroe said that "We had a green light to use deadly force against any armed adult male." And Mark Tilton said, "We were told that we should use deadly force if no children were endangered."

That doesn't sound like the deadly force standard policy to me. The Denver SWAT team had a very different attitude. Their team leader told his team members the rules, then directed them to basically ignore the rules. First he told his team members the rules, and then he told them to basically ignore the rules and apply deadly force standard policy. In fact, when one of the SWAT team members heard the rules, he said, "You've got to be kidding."

So I would like to ask you this: Is it reasonable to believe that the rules saying that you "can and should" use deadly force might very well have had some impact, especially on the second shot?

Mr. FREEH. They might have had some impact. Again, I think as a matter of evidence, we have to rely on what the witness said under oath, both on direct and cross examination. You had the individuals here for your own examination. My view of it is that the rules obviously were known by everybody on the scene. One group of agents said they were wrong; we didn't follow them. The other group of agents—more knowledgeable and more aware of the deadly force policy and its application—said that we read them, but we still knew that we had to make the individual decision whether to employ necessary force or not.

That is actually a correct statement of what the deadly force should be. But the basic problem is we should have never had rules of engagement. The fact that they would confuse, or that we are having this conversation about influence, shows that they are absolutely unnecessary, confusing, and we should never have used them.

Senator KOHL.

All right. Director Freeh, the American people have been shaken by Ruby Ridge in relationship to their estimate of the FBI and how it performs. How do you place Ruby Ridge on the scene in America with respect to its impact on the people of this country? And how do you hope to see that impact, if it has been negative, repaired?

Mr. FREEH. I think it certainly has had a negative impact on people's image of the FBI, maybe law enforcement in general; maybe, unfortunately, government in general. I think the mistakes that were made here were grievous. I think the aftermath of the mistakes in many instances is worse in some ways than the actual misjudgments on the scene, if there were any.

But I think you've got to look at it in context. This is still the FBI that works on the oak bomb case, that works on the two trade bombing cases in New York, that solves the Ames case, that rescues 4-year-old boys-last Monday—from a kidnapping situation. We are the people committed to protecting the people of this great Nation.

We do make mistakes. As long as I recruit from the human race, we're going to make mistakes. And I think the answer is to hold us accountable for those mistakes; hold me accountable for those mistakes. Have hearings like this: Have the scrutiny of police forces and FBI that we only see in the United States. I think peopie should take great comfort from that.

The FBI is not above the law. We are subject to criticism. We are subject to review. We are subject to fixing things in a, which we needed to fix here very badly for a long time. But I think people have to remember that the great number—the 24,000 people in the FBI— every day are working to protect the people of this great country. And they should have great confidence in that and not be discouraged from what is a terrible series of blunders and mistakes, but mistakes which I believe can be fixed.

We have to have the support and confidence of the people of this country to do our job. I hope we have it. I'm going to work very hard to maintain it and ensure that these instances are as rare as they actually are here and not commonplace within the FBI.

Senator KOHL.

Thank you very much, Director Freeh. I have great confidence in you, in your experience, your integrity, and your ability to do all the things that you just said you are going to do. Thank you very much.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Senator SPECTER. Thank you, Senator Kohl.

Senator Thompson.

Senator THOMPSON.

Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman.

Director Freeh, I first of all want to commend you for not only the work that you have done, separate and apart from this particular matter, but the reforms that you have set in motion. I think they go a long way toward curing some of the problems that we have had.

I think that we are dealing with a fine line here when we are investigating our law enforcement agencies. A lot of us approach it with very mixed emotions. We have got to get to the bottom of things when we are confronted with them, hopefully clean them up, acknowledge mistakes, and then move on.

I think in times past we have dealt too much on the negative side. There is a severe crisis of confidence I think now, not only with regard to law enforcement agencies but institutions in general, and none of us wants to be a part of contributing to that. But we have trouble moving on when we still have unfinished business like these rules of engagement. I think it is very unfortunate that we can't spend all of our time talking about the future—talking about these changes that you have instituted—instead of having to go back over the past with regard to the rules of engagement, for example.

But the problem is that it is not just the past. It is also the future, because we are talking about what the deadly force policy of the FBI is now and will be in the future and what circumstances fit under it and what circumstances do not. And if the Director of the FBI has taken the position that people who are running from snipers who are at a great distance, who have them scoped, and are trying to get into their house and are shot while they are running into the house, is consistent with the deadly force policy, then I think we have got a problem.

It looks to me like Agent Horiuchi was faced with a situation at trial somewhat like this. He had shot Randy Weaver. He had shot Kevin Harris. They posed no threat to anybody at the time he shot them. But he was doing it pursuant to rules of engagement that were clearly wrong. Everybody acknowledges that they are wrong; basically a "shoot on sight" policy. He was consistent with the rules of engagement because they were carrying firearms and they were adults. That is the only qualification.

So he apparently felt that he couldn't maintain that position. He had to embrace the standard deadly force policy and take the position that this was really all right under the standard deadly force policy of the FBI. And everybody else has kind of fallen in line. But the only problem with that is that there had to be some factual circumstances that supported it. There had to be facts that would lead someone to believe that somebody was in imminent threat of death or bodily harm. So, therefore, you had the helicopter justification.

Now, why the FBI would send a helicopter in under those circumstances, knowing that these people would run out of the house to look, knowing that they would be armed, is another question. But then they run for the house, and he shoots another person— not the person that allegedly aimed at the helicopter. And, of course, the facts from the bullet entry and exit and all do not bear out the theory that he was aiming at anybody. But assuming that was the case, he shot a second person—a different person, a person not aiming at a helicopter, a person not accused of posing a threat to anybody—as he was running into the house.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, the answer to that was well, he thought it was the same person. So we have a sniper, who can apparently hit a silver dollar at 300 yards, not even knowing who he was shooting at. But that is still better, I suppose, than being wed to the unconstitutional rules of engagement.

Now, Agent Horiuchi was in a bind. And it is my guess that that is kind of the analysis that he went under and it unfortunate, but I guess it is somewhat understandable. But I think it is a little bit more of a problem when the Director of the FBI says that he can't pass judgment on these circumstances.

It is clear—to me, anyway—that under the standard policy these people who were running for the house did not pose a threat to anybody. And you say, you weren't there; you can't judge. That is exactly what you have got to do. If it is an objective standard, isn't that now what you have got to do, be the trier of fact? Somebody has got to make the determination. In the future when an FBI agent shoots somebody running into a house, saying that he thought maybe later on he might take a shot at me from the house, are you going to take the position that I wasn't there so I can't pass judgment on what he did?

Mr. FREEH. Senator, that is not my position. I have made a judgment here. My judgment is that, based on those facts and circumstances—now you draw different inferences from the facts and you challenge the credibility of the witnesses. You are certainly entitled to do that; I do not. So based on my understanding of the facts, I have come to a judgment. My judgment clearly is that it was a constitutional shot.

That doesn't mean that it was a good shot. It can be a constitutional shot and a bad shot at the same time. But the very narrow issue—certainly the issue for me, and the issue for the Civil Rights Division that passed on this in a consistent manner—is that the shot, under all of the Supreme Court tests, is reasonably objective. It doesn't mean that it's not a close question.

In March of this year, the third circuit looked at the MOVE case. If you remember the MOVE case in Philadelphia, an incendiary device was dropped on a building, both with subjects and children, caused a fire, and there were terrible deaths. The third circuit split two to one, the majority saying that it was arguably reasonable to drop the incendiary device on the building.

So I am making a judgment here. I'm saying that it's a very close and very difficult question, but under all the circumstances I come down on the side of a constitutional shot.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, we are mixing apples and oranges here a little bit,

Director, because the OPR and the Civil Rights Division looked at this matter primarily from the standpoint of criminal prosecution. Nobody is arguing, and—I am certainly not arguing, that there ought to be criminal prosecution in this case. That is not the test.

The test, as far as what I am concerned about in the future of the FBI and the way people look at the FBI, is whether or not what happened is consistent with the FBI's deadly force policy. And it seems to me that it clearly is not. Whether it is constitutional or unconstitutional, whether it has criminal ramifications, has civil ramifications—I am not getting into all of that, whether it is 1983 or a criminal violation. I am simply interested in whether or not you are taking the position that these people were running for cover—not escaping.

Now, the Garner case had to do with somebody attempting to escape, and they said there that even if it was a felony, even if he was attempting to escape, that under those circumstances it would not justify deadly force. But in this case, they were running back to their own house. I am not talking about them. They have enough blame to go around.

I am talking about the future of the FBI and the way people perceive it. You take the position that under those circumstances the shot was consistent with the FBI policy which basically said that you can use deadly force if somebody is in imminent danger.

Mr. FREEH. I have two answers to that. The first answer is that using the Graham standard, which is judging that decision from the shoes and eyes of the person at the time, it was a constitutional shot consistent with policy. Looking at it today, I would not take that shot. There is nobody in the FBI who would take that shot given what we know about the facts and circumstances. But that is the exact difference between hindsight and the split-second decision that Justice Rehnquist says you have to make.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, do we agree that it is an objective standard?

Mr. FREEH. Well, no. What we—

Senator THOMPSON.

That is not what Garner says?

Mr. FREEH. Garner says it's a standard of objective reasonableness. But that is the reasonableness in the shoes and eyes of the person making the decisions.

Senator THOMPSON.

What is the difference between that and a subjective standard?

Mr. FREEH. A subjective standard, which the Garner majority rejected, is looking at the intent or motivation of the person making the decision. Garner said that is irrelevant here because they replaced, for fourth amendment purposes, the objective standard of reasonableness. Now, that is something a court can use 2½ years down the road.

Senator THOMPSON.

A reasonable person under the circumstances facing that individual.

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir.

Senator THOMPSON.

And a trier of fact has to make the determination as to whether or not that was reasonable under the circumstances. You have been a judge. You have done that.

Mr. FREEH. Yes.

Senator THOMPSON.

You call it second-guessing, but that is what judges do half the time, isn't it?

Mr. FREEH. Yes.

Senator THOMPSON.

I mean, somebody has to make that determination. So what we know—as you say, not looking at it through Mr. Horiuchi's eyes but knowing what we know now and knowing what he knew then, we still say that that was consistent with FBI policy? Is that what you want? Do you want your agents out in the field to think it appropriate to shoot under a set of circumstances such as this: People running for the house, under some notion that they might shoot from the house later on, I suppose—even though there is no record, no indication that they ever shot from the house before. Do you want your agents believing that shooting these people, as they are trying to run through the door and get in the house, is consistent with policy which says they can only shoot when they are under imminent threat of loss of life or bodily harm?

Mr. FREEH. Absolutely not. I do not want that, and that's why we're going to train against a scenario where, when we have a retreat, deadly force should not be used. But, you know, I have sat down and I have not only thought about this a lot, but I have talked to a lot of people—

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, excuse me. If you have a retreat, deadly force should not be used. That is what you are going to train against. Is that position that you have just articulated, is that FBI deadly force policy?

Mr. FREEH. If there is a retreat where there is no imminent harm to the officer or anyone else, deadly force policy should not be used; correct.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, that was the situation in this case, though, wasn't it?

Mr. FREEH. That is the situation in 1995. That was not the objective reasonableness test that would have to be applied to Horiuchi at the scene. Those are the apples and oranges. We can say now

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, I am not sure where we are here. This has kind of gotten into the stratosphere. What you are saying is that, from now on, you are going to train your people that under a retreat, where nobody is under imminent danger, they should not shoot?

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir.

Senator THOMPSON.

And I say, is that consistent with policy? You wouldn't be training against policy. So the answer to that is:

Yes; that is what our policy is. Right?

Mr. FREEH. Right.

Senator THOMPSON.

All right. Under these circumstances that is what was happening in the Weaver case. They were retreating into their house. The snipers were hidden. Nobody was under any imminent threat. Isn't that true? Can't we say that? Isn't that the objective standard and test that we've got to apply now?

Mr. FREEH. That's true in 1995. It was probably true a minute after that shot was fired. But let me tell you what the constitutional scholar told me: He said if one of those individuals had entered the house, or from someone already inside the house a shot was returned in response to the second shot, we would have a whole set of reasonableness standards and a whole different set of judgments to make.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, I am not the least bit interested in what might have happened later on that did not happen. But I think I would just point up my problem here. I think we ought to be able to spend a lot of time on these changes that you have made. You have done a good job at them. You have done a good job at the FBI. I think it is just a shame that you have gotten hung up and locked into a position that Horiuchi evidently took on the witness stand that is totally, totally untenable.

You have a good deadly force policy, and you have an objective standard that you are going to have to apply in disciplining your people in the future. And judges are going to have to apply it in 1983 cases, or criminal cases, or whatever. And I just wish you would continue to consider whether or not on the entire record, including the task force conclusion, this second shot was not consistent with your standard deadly force policy.

You have been an FBI agent. You have been a Federal judge and seen many cases, and now you are the Director. Do you know of another case where FBI agents shot someone running into their own house and defended it on the basis of it being consistent with deadly force policy? Or do you even know of a case where agents shot anybody running into their house, retreating?

Mr. FREEH. I know some seventh circuit cases: Stark, which, of course, was decided post-Garner, where an armed bank robber in flight, not putting anybody under any imminent or immediate harm, was shot and a court of appeals has said that that was a justified and constitutional application of deadly force.

Senator THOMPSON.

Was he running into his own house?

Mr. FREEH. No. He was escaping.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, then, that is not the kind of case I was asking. Do you know of any case like this where an agent shot someone running into their own house?

Mr. FREEH. No, sir; not identical to these facts.

Senator THOMPSON.

I don't either. Let me ask you this: You applauded the settlement with the Weavers, and yet you basically take the position that the second shot was justifiable both from a criminal standpoint and a civil standpoint, as I understand it. You don't think there is any exposure there. Why do you think the Government settled with these people for $3 million if there was no civil exposure?

Mr. FREEH. Senator, I don't say it's justifiable. I specifically say it’s justifiable. I said it's constitutional. There's a wide difference with respect to that.

Senator THOMPSON.

If the action had been consistent with standard rules of engagement, don't you think there might have been a defense that the Government would have asserted under these circumstances?

Mr. FREEH. The Government always asserts defenses under any circumstances. This was a decision made by the Civil Division, and ultimately the Attorney General, to settle the case. I think it was appropriate to do so. I think there is a healing aspect to it which is very important. And I thoroughly endorse the settlement.

Senator THOMPSON.

Well, you know, I think there probably is a healing aspect too, but my experience with the Government is that they don't open up the Treasury for healing purposes. They take a very careful legalistic view of these things, and I think they concluded early on—and rightfully so—that the second shot was totally unjustifiable.

On another point, you are talking about now that since this occurrence that you are not going to have rules of engagement. Up until now, who has had the authority to establish rules of engagement?

Mr. FREEH. That was one of the big problems I found here. We had no written policy anywhere saying who was responsible for formulating rules of engagement and approving them. The practice in 1992, in August 1992, was that the field commanders or the HRT commander or the SWAT commander would formulate the rules of engagement; they would be approved by an SAC field commander.

Senator THOMPSON.

Would there necessarily have to be rules of engagement?

Mr. FREEH. There would not necessarily have to be. That was an optional feature.

Senator THOMPSON.

And the onscene commander could make that determination?

Mr. FREEH. Without headquartes.

Senator THOMPSON.

And they were supposed to be more limiting, as far as action of the agents is concerned. Is that correct?

Mr. FREEH. They are supposed to restrict constitutional power.

Senator THOMPSON.

All right. Now, in your statement here, in terms of what the situation is now, you say there are no rules of engagement and the standard deadly force policy will be the sole standard, although onscene commanders will be permitted to further restrict the use of deadly force as necessary.

Mr. FREEH. Yes, sir.

Senator THOMPSON.

So there has really not been any change, has there?

Mr. FREEH. Oh, no. There has been a great change. What that means is that the field commander can say, don't shoot under any circumstances, even if you are taking fire, even if you get shot, do not return fire.

Senator THOMPSON.

That is what happened under rules of engagement, was it not? I mean, the purpose of rules of engagement

was to say, even though under the standard policy you would have the right, we are going to limit you.

I am not criticizing this. In fact, I would be concerned if you didn't give some discretion to having less. In a hostage situation, for example, where somebody's life clearly is in danger, you still might not want to shoot.

Mr. FREEH. That's correct.

Senator THOMPSON.

And that is the proper use of rules of engagement. I question whether or not you ought to do away with them. It doesn't look to me like you really are. You are still giving commanders the onscene authority to limit the scope of the action of the officers there. It looks to me like you have basically got what you used to have in the old days, which worked properly and very well, as far as I know, up until Ruby Ridge.

So I would encourage you not to throw out a policy that is good just because of Ruby Ridge. You got in trouble on Ruby Ridge because you did not follow your policy in that the rules of engagement that came down were more expansive instead of more limiting. Just a thought for your consideration.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Mr. FREEH. Thank you, Senator.