Biographic Sketch of Edman Spangler

Edman Spangler's Role in the Conspiracy

Images

Biographic Sketch of Edman Spangler

Edman Spangler was born in York, Pennsylvania on August 10, 1825. During the Civil War, Spangler worked at Ford's Theatre in Washington as a carpenter and scene shifter. Witnesses described Spangler as "a very good, efficient drudge" who was "harmless" and a "heavy drinker" that lacked "self-respect." He usually slept in the theater. Through his work at Ford's, Spangler met actor John Wilkes Booth. Spangler often tended to Booth's horse when he was at the theatre.

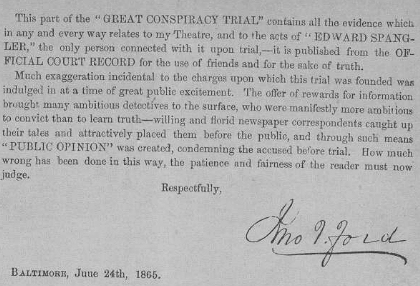

Edman Spangler's Role in the Conspiracy

On April 14, the day of Lincoln's assassination, Spangler helped prepare the State Box for the president. He removed a partition separating two boxes, creating a larger one for Lincoln and the other members of his party. While working on the box, Spangler allegedly made derogatory remarks--such as "Damn the President!"--about Lincoln. (On the other hand, a defense witness testified that Spangler smiled and clapped along with other theater workers when the president arrived at Ford's.)

Sometime between nine and ten o'clock, Booth appeared at the rear of the theatre and called for Spangler. Booth asked Spangler to hold his horse. Spangler in turn asked Joseph Burroughs (better known as "Peanuts") to watch Booth's horse. When Peanuts told Spangler that he "had to go in to attend my door," Spangler said he should hold the horse anyway and "if there was any thing wrong to lay the blame on him."

Immediately after the shooting of Lincoln, Spangler hit Jacob Ritterspaugh, another Ford's employee who followed Booth out the rear door and observed him head down an alley on his horse. Ritterspaugh testified that when Spangler slapped him on his mouth he said, "Don't say which way he went." Spangler was convicted almost entirely on the testimony of Ritterspaugh. Defense witnesses were offered to contradict Rittersbaugh's testimony. James Lamb testified that after Booth's exit, when Ritterspaugh returned to the stage, he said, "That was Booth! I'll swear it was Booth!" According to Lamb, Spangler responded by slapping Ritterspaugh and saying, "Shut up. What do you know about that? Hold your tongue." The words attributed to Spangler in Rittersbaugh's testimony would probably constitute aid in furtherance of Booth's escape, while Lamb's version (supported by another defense witness) would probably not be a crime.

Spangler was questioned the day after the authorities, then arrested on April 17 and charged with being an accomplice to Booth.

Edman Spangler on Trial

At the 1865 Conspiracy Trial, in addition to the key Rittersbaugh testimony, prosecution witnesses reported seeing Booth on the evening of the assassination, standing at the back door of the theatre and holding his horse and calling for "Ned" Spangler. John Sleichmann, a property man for the theatre, testified that he saw Booth enter the back door of the theatre and ask Spangler, "Ned, you'll help me all you can, won't you?" According to Sleichmann, Spangler replied, "Oh, yes." Joseph Stewart, a theatergoer with a front orchestra street who ran after Booth across the stage yelling, "Stop that man!," testified that he was "satisfied" that Spangler was the person he saw near the rear door who was in a position to block Booth's exit if he had been so inclined. Finally, John Miles, a Ford's employee, testified when he asked Spangler who it was he saw holding Booth's horse before his escape, Spangler replied, "Hush, don't say anything about it."

Spangler's defense attorney, Thomas Ewing, argued that while the prosecution evidence might suggest Spangler agreed to assist

Booth on April 14, it failed to prove that Spangler was aware of Booth's guilty purposes in requesting his assistance.

The Military Commission found Spangler guilty and sentenced him to six years in prison.

Spangler served a year-and-a-half of his sentence at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas before being pardoned by President Johnson in March, 1869. After his release from prison, Spangler accepted Dr. Samuel Mudd's offer of five acres of farmland near Mudd's home in Maryland. He lived there from 1869 to 1875, when he died.