1844-1865

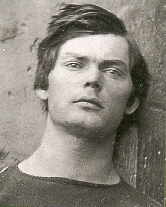

Biographic Sketch of Lewis Powell

Lewis Powell's Role in the Conspiracy

William Doster's Trial Summation in Defense of Lewis Powell

Images of Lewis Powell

(Harper's)

Secretary Seward

(Harper's)

(Police Gazette)

(Frank Leslie's)

(Harper's)

Biographic Sketch of Lewis Powell

Lewis Powell was the youngest boy in a family of eight children. He spent the first three years of his life in Randolph County, Alabama, the next twelve in two rural Georgia counties, and the two years before his departure to join the Confederate Army at age seventeen in Live Oak, Florida. Powell's father was a Baptist minister, school master, and farmer.

Biographers describe Powell as a quiet, introverted youth who enjoyed fishing and caring for sick and injured animals. His fondness for nursing animals led his sisters to give Lewis the nickname "Doc."

In 1861 Powell joined the 2nd Florida Infantry. Wounded at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, Powell was captured by Union troops and consigned as a POW nurse at Gettysburg Hospital.

While at Gettysburg Hospital, Powell developed a relationship with a volunteer nurse named Margaret Branson. Transferred to West Buildings Hospital in Baltimore in September 1863, Powell--most likely with the help of Branson--escaped within a week of his arrival.

Powell fled Baltimore, finding his way behind lines to Virginia, where he met up with and joined a Confederate Calvary outfit known as Mosby's Rangers. Fellow rangers described young Powell as "chivalrous, generous, and gallant" and as "always keyed up for battle." While serving in the Mosby's Rangers, it is likely that Powell began his involvement with the Confederate Secret Service.

In January 1865, Powell again crossed lines, claiming to have deserted his regiment. Powell signed the Oath of Allegiance to the Union using the alias "Paine." He settled in Baltimore, where he stayed at the boarding house of Margaret Branson's. While in the Branson house, Powell violently assaulted a black maid who refused to promptly clean his room as he had ordered. According to a witness, Powell "threw her on the ground and stamped on her body, struck her on the forehead, and said he would kill her." The assault led to Powell's arrest, but charged were dropped after witnesses failed to appear.

Lewis Powell's Role in the Conspiracy

A Confederate operative, David Parr, introduced Powell to John Surratt, who in turn introduced Powell to John Wilkes Booth. Booth recruited Powell, along with other conspirators, to participate in the kidnapping of President Lincoln. Booth planned to kidnap Lincoln on March 17 as he attended a play at the Seventh Street Hospital, then take him to Richmond where would be held in exchange for Confederate POWs. The plan collapsed, however, when Lincoln cancelled his appearance at the play.

The kidnap conspiracy turned into an assassination conspiracy by April. Powell agreed to participate in Booth's plot to assassinate high government officials in the hopes of throwing the federal government into chaos. Powell's assigned role was to enter the home of Secretary of State William Seward and kill him as he lay on his bed recovering from a recent carriage accident.

The conspiracy began to unfold around eight o'clock on April 14, when Powell met with Booth, who gave him weapons and a horse. At ten o'clock Powell and David Herold arrived at Seward's home in Washington. Powell told the servant who answered the door, William Bell, that he had a prescription for Secretary Seward from his doctor. Over Bell's objections, Powell began walking up the steps toward the Secretary's room, when he was confronted by the Secretary's son, Frederick Seward. Seward told Powell he would take the medicine, but Powell insisted on seeing the Secretary. When Seward resisted entry, Powell clubbed him violently with his revolver (fracturing Seward's head so severely that he would remain in a coma for sixty days), then slashed the Secretary's bodyguard, George Robinson, in the forehead with a bowie knife. Finally reaching the Secretary in his bed, Powell--shouting, "I'm mad, I'm mad!"--stabbed him several times before he could be pulled off by Robinson and two other men. Powell raced down the stairs and out the door to his one-eyed bay mare. Attempting to flee in the direction of the Navy Yard bridge, Powell instead made a wrong turn and ended up spending the night in a cemetery near the Capitol

Powell at Trial

Powell was arrested on April 17 after he showed up at Mary Surratt's home with a pick-axe while she was being questioned by a party of military investigators. Powell--at the unlikely hour of eleven p.m.--claimed to have been hired to dig a gutter. Mary Surratt refused to back up his story and he was arrested on suspicion of his involvement in the assassination plot. When William Bell identified Powell as Seward's attacker, Powell laughed. Further confirmation of Powell's guilt came in the form of blood spots found on the inside sleeves of his jacket and shirt. Authorities also made out the barely legible lettering inside his boots: "J W B - th."

Louis Weichmann, a boarder at Mary Surratt's home, identified Powell as the man who called himself "Wood" and who frequently called at Surratt's, where he would sometimes engage in two or three hour private conversations with Booth and John Surratt. Weichmann said Wood claimed to be a Baptist preacher, but--suspiciously--wore a large false moustache.

At the military trial, Powell's attorney, W. E. Doster, argued not that Powell was innocent, but that his life should be spared because he suffered from a fanaticism that bordered on insanity. "I say he is the fanatic, and not the hired tool," Doster told the Commission. "He lives in that land of imagination where it seems to him legions of southern soldiers wait to crown him as their chief commander." Doster said that when he asked Powell why he did it, he replied, simply, "I believed it was my duty." Doster described Powell as an innocent farmboy turned assassin by circumstances beyond his control: "We know now that slavery made him immoral, that war made him a murderer, and that necessity, revenge, and delusion made him an assassin." Doster ended his remarkably eloquent plea for Powell's life by asking the Commission to "Let him live, if not for his sake, for our own."

LINK TO DOSTER'S SUMMATION

Unlike the other conspirators, Powell maintained an appearance of indifference to the trial proceedings. Doster said Powell would "sit like a statue" and "smile as one who fears no earthly terrors."

After attempting suicide by banging his head against his cell wall, Powell was forced to wear an uncomfortable padded hood. He told his guard, John Hubbard, in mid-May that he was "tired of life" and would "rather be hung" than forced to "come back into the courtroom." Adding to his discomfort through much of the trial was his severe constipation--Powell had no bowel movements from April 29 to June 2.

The Commission found Powell guilty and sentenced him to death. Powell died on the gallows in the courtyard of the Old Arsenal Building along with three of his fellow conspirators on July 7, 1865.

In 1992, Powell's skull turned up in the Anthropology Department of the Smithsonian Institution among a collection of Native American skulls. The skull was returned to a Powell relative who buried it in a cemetery in Geneva, Florida.